An empty landscape?

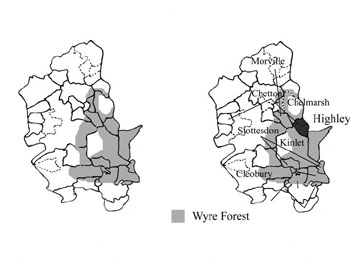

(This is a speculative reconstruction of how the area around Highley might have looked c700AD, when it and many surrounding villages first acquired their current names. The map also shows spot finds of Bronze Age and Roman-British objects.)

(This is a speculative reconstruction of how the area around Highley might have looked c700AD, when it and many surrounding villages first acquired their current names. The map also shows spot finds of Bronze Age and Roman-British objects.)

Writing around 1960, the famous architectural historian Niklaus Pevsner claimed that Shropshire had little to interest archaeologists. By this he meant that the County had few spectacular pre-historic monuments such as stone circles or long barrows. Indeed, compared to some other counties, this is a fair comment. At the time Pevsner was writing, the evidence for significant human settlement in Shropshire prior to the Romans was limited. However, in recent years this has changed, largely due to aerial archaeology. Many will know about crop marks. Even a very flimsy building may leave traces in the ground; richer or poorer patches of soil where it once stood. This in turn alters the growth of crops so that some ripen more quickly than others. At the right time of year, ancient walls and boundaries may be seen from the air, as lines against an otherwise uniform fieldscape. Crop marks may only be visible for a few days each year and depend very much on what is being grown in the field as to their visibility. The probability is that we currently only have a very incomplete record of all crop marks in the county. Nonetheless, many have been recorded and sometimes it is possible to make some good guesses as to what they represent without excavating them. A common feature is the “ring-mark”, a circle, typically ten to 20 yards in diameter. This often represents a “round barrow”, a form of burial chamber in use in the Bronze age, about 4000BC. These consisted of a circular heap of earth in which cremations were laid. They were surrounded by a ditch and it is this that gives the circular crop mark. Another characteristic feature is the “rectangular enclosure”. These have often been shown to be late Iron Age or Roman farmsteads; in some particularly good examples, not only the farm itself can be made out, but also the surrounding fields. Other features, such as curved enclosures, are much harder to interpret but may also be pre-historic.

Extensive campaigns of aerial archaeology have shown that the landscape around the upper Severn valley is dotted with features such as these. It has been suggested that, in this area, the population approached that seen in the Middle Ages. Less is known of settlement in the south of the county, in our area. This might not be considered particularly favourable for farmers; the soils are often heavy clays and the Wyre Forest gives the impression that it once extended far beyond its present boundaries. However, recent work has suggested that this might not be the full story. Aerial archaeology has now shown a variety of interesting features around Chelmarsh and Kinlet. Close to Hampton Loade there are curved and rectangular enclosures visible from the air; around Catsley Farm there are two more enclosures as well as a ring ditch. To these features can be added the well-known Roman camp at Wall, Town Farm in Neen Savage, on the road to Cleobury Mortimer, and also what was apparently once an Iron Age fort at Kingswood in Kinlet, recorded by 19th century antiquarians but now invisible. There are also the occasional pieces of flint found around Highley and Billingsley.

Without proper investigation, it is difficult to know what any of these features mean. Crop-marks can be a disappointment when dug by archaeologists; they are sometimes as a result of natural features. Nonetheless, there do seem to be suggestions that people have been settled in this area since the Bronze Age and that by the time of the Roman Conquest the wood had been cleared from the better soils to give a pattern of farms and fields, not entirely unlike the present-day landscape. Whilst there are no documents to confirm this, the evidence may yet emerge from the soil to show that the equivalent of the Highley Initiative existed over 2000 years ago!

A wooded landscape

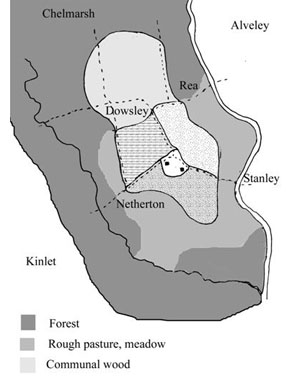

(This map shows a speculative reconstruction of the extent of the Wyre Forest in middle Saxon times. It also shows ancient parish boundaries, most of which would have been estates at this period. It is suggested that the large outlying parishes were each given one or more estates on the fringes of the forest, to provide woodland.)

Above, I speculated on how the countryside around Highley looked during the period before and during the Roman Occupation. There is increasing evidence that the area was dotted with farms; whilst these would have been more sparse than currently, it is clear that the area was far from virgin forest. However, we know nothing about the people who lived and worked these farms; the historical record is virtually silent until the Domesday Book of 1086. So what happened between the end of the Roman Occupation and the Norman Conquest; can we say anything about the Anglo Saxons who were, in all probability, the first people to live in villages (as opposed to scattered farms) in this part of Shropshire?

There are in fact two sources we can use: Domesday Book itself and place name evidence. Although written in 1086, Domesday in fact gives us a glimpse into Anglo Saxon society; with careful detective work, it can shed light on conditions that existed long before it was written. Place names give us a more direct window on the early Anglo Saxon period; most local place names seem to date from the 7th century, when the Saxons first established themselves politically in this part of the world. The names reflect the landscape they saw: the woods, the valleys, the hills and the marshes. Of particular relevance is the word leah, an old English term which at this time meant a wood or a woodland clearing. This was normally preceded by something to describe the clearing: the name of the person who lived there, its shape or something else. Today, leah has become ley, as in Highley, Billingsley and Glazeley. These names show us that there was a belt of woodland extending north from the Wyre Forest, following the valley of the Borle Brook; by contrast, places such as Chetton, Stottesdon and Chelmarsh were less extensively wooded.

In the early Middle Ages the balance between wooded and non-wooded areas was very important. Settlements needed open country for the fields to grow their crops. However, woodland was also required. It provided timber for building, firewood for fuels, grazing for animals and game for food or sport. Domesday Book describes both the size of the fields under the plough and also any woodland associated with a settlement. In the case of Highley, it had a wood sufficient to pasture 36 swine. Pigs were an important part of the diet and were able to feed themselves on acorns in woodland. It is difficult to know just how big the wood would have been; perhaps 200 acres based on comparisons with other parishes.

Domesday Book also gives information about who owned the parish (or, strictly speaking, the manor). Here, it is sometimes possible to see interesting patterns emerge. Highley belonged to the Countess Godiva in 1066, Lady Godiva of popular legend. Godiva would have been a widow at this time and it is likely that the village had originally belonged to her husband, the Earl of Mercia, but had been given to her to provide her with an income after his death. The only other parish in this part of Shropshire that also belonged to Godiva was Chetton. The fact that the two parishes were linked in this way suggests there must have originally been a close connection between them. Chetton seems to have once been a much larger estate than it is at present. One possibility is that it originally held Highley to give it access to woodland. This pattern can be seen elsewhere, where parishes on the fringe of the Wyre Forest are associated with much larger estates which would otherwise lack woodland. Thus Glazeley was once incorporated into Chelmarsh, Billingsley was a detached part of Morville and parts of Kinlet in the Wyre Forest were originally attached to Stottesdon. It may be that this is a reflection of the way the very first Saxon officials in the late 600’s set out their estates, to ensure they all had access to the woodland that they needed.

Vanishing villages

We tend to think of the countryside as timeless and permanent; ancient villages that have changed little in generations. It is certainly true that most of our local villages were mentioned in the Domesday Book and so are well over a thousand years old. However, their history has often been much more turbulent than many people realise.

From the Anglo Saxon period to the start of the 14th century, there was a steady growth in the population. Of course, episodes of war and disease did occur from time to time but the overall trend was upwards. Thus the villages recorded in the Domesday book were expanding communities and this can often be seen in the entries in the book itself. Woodland was being cleared to bring more land into cultivation and new houses were being built. New communities grew up outside the heart of the old established villages. Thus at Highley, Netherton in the south-east of the parish is an example of a “daughter” settlement, founded by villagers looking for new land on which to settle. Sutton in Chelmarsh and Norton in Kinlet are similar examples; these simply mean “south settlement” and “north settlement”, being respectively south and north of the main communities.

At the start of the 14th century, there was a marked change in conditions. A series of poor harvests caused widespread hunger and malnourishment. The effects of these were compounded by disease which killed off much of the livestock. Then, in the middle of the century, plague struck. The Black Death may have killed up to a third of the population and its effects in Shropshire were no different from most other parts of the country. As a result, there was widespread depopulation. Whilst no parishes were totally wiped out, every village must have shrunk in size and some of the outlying communities never recovered. An excellent example of a deserted medieval settlement is at Detton Hall, in Neen Savage. This is a fine, half-timbered building which was the manor house to a small community that once had its own chapel. However, all that is left of the hamlet of Detton is a series of shallow earthworks; the bases of long abandoned houses and hollow ways where there were once roads. In Sidbury, next to the church, there are similar remains of abandoned houses. Sidbury is an example of a shrunken medieval settlement; the village survived, but in much reduced circumstances and never recovered to its former population level.

In some cases, there are no physical remains and historical detective work is needed to locate the vanished hamlets. One way of doing this is by place name. Sutton in Chelmarsh is today no more than a handful of houses at a road junction, but the name suggests that it was more substantial in medieval times. In Kinlet, Norton’s End is now a farm, but the name shows that it was once on the outskirts of a distinct community (it was literally at the far end of Norton- the “north town” in Kinlet). In Highley we have the farm of Woodend, showing the limit of a wood that extended north into Chelmarsh. Today this is just a single farm, but 16th century deeds show that this was formed from four distinct holdings named after their former occupiers: Thatchers, Pountneys, Barnards and Holloways. Furthermore, there was a chapel here; the Lady Chapel. By the mid-16th century all of this had gone; in all probability the four small holdings were amalgamated into the single farm of Woodend by the tenant who took over once the Black Death had passed in the later part of the 14th century. This story could be repeated at almost all the shrunken and deserted settlements around here.

Moving villages

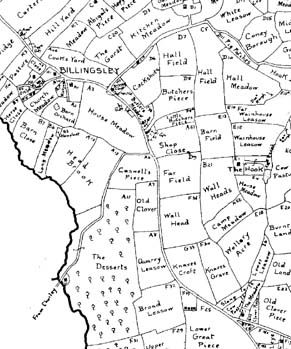

(This map shows the village of Billingsley about 1840, taken from the tithe map copies of H. G. Foxall. The original village was by the church; however, mining activity has caused the centre of population to move south, to the junction of the road leading to Highley.)

(This map shows the village of Billingsley about 1840, taken from the tithe map copies of H. G. Foxall. The original village was by the church; however, mining activity has caused the centre of population to move south, to the junction of the road leading to Highley.)

In the previous article, I wrote about the way some villages and hamlets have shrunk or even disappeared over time. This is perhaps the most dramatic illustration of the way in which settlements within the countryside have the potential to change their size and appearance. However, even apparently stable villages can have very complicated histories that can only be unravelled by careful detective work.

Villages can move over time. A good example of this is Billingsley. Today, although small, the centre of Billingsley is unmistakably by the Cape of Good Hope, at the junction of Bind Lane with the main Bridgnorth-Cleobury road. However, the church sits in relative isolation almost a mile away, with just a couple of farms and cottages for company. In most villages, the church marks the original centre of the community and this is almost certainly the case with Billingsley. “Hall Farm”, in Covert Lane but close to the church, may have been the site of the manor house and there would have been a scatter of houses and cottages between the two. In medieval times, these would have been surrounded by large, open fields where each tenant had a few strips of land to cultivate; the last vestiges of these strips may be seen in a field a little north of Hall Farm. Around the edge of the parish, the more independent farmers would establish their own holdings; one of these would have been at Southall Bank, just over the other side of the road from the Cape, towards Chorley. Over the years, Billingsley would have shrunk like most villages in the area and many of the cottages and small farms would have been abandoned. However, at the start of the 19th century, this process was reversed by the opening of a large coal mine and a blast furnace close to Southall Bank Farm. The Cape of Good Hope was built to serve the workmen and it is possible that the main Bridgnorth-Cleobury road was diverted to run past it. Thus the centre of the village moved from the church to the mines. Although this first phase of industry vanished almost as quickly as it arrived and most of the miners’ houses were abandoned, the Cape remained. When coal mining resumed at the end of the 19th century, the new pit was again sunk close to the Cape. Whilst ultimately this again bequeathed to Billingsley just a couple of new houses and a row of “temporary” tin bungalows, these survived long enough to influence the late 20th century planners and so the present small village grew up. So, in the course of about 200 years, almost the entire village has moved to the far south of the parish.

A rather similar pattern seems to be present in Chorley. Here it is likely that Chorley Hall marks the original site of the community. Again, coal mining in Lower Chorley and Harcourt meant that most of the houses were built about 0.5 miles east of the hall; now, infill is gradually bringing the two parts of the village together again.

Industry is not the only reason for communities moving. Kinlet Church, like Billingsley Church, sits far from the present centre of the village around the Eagle and Serpent pub. In this case, the old village was probably cleared by the squire, William Childe, when the present Kinlet Hall was built in 1729. The Cape was conveniently sited to serve traffic on the main road and the building of the village school close by in the 19th century helped to establish this as the new centre of the community. Thus whether by accident or design, many of our settlements are not in their original positions.

Planned villages

(This survey of the Childe estate property in Cleobury shows how the town retains some of its medieval planned form, with a central High Street and long, narrow burgage plots leading off from this. Around the perimeter are back lanes. However, there are probably more complicated elements in the plan; the curved shape of the High Street is unusual.)

(This survey of the Childe estate property in Cleobury shows how the town retains some of its medieval planned form, with a central High Street and long, narrow burgage plots leading off from this. Around the perimeter are back lanes. However, there are probably more complicated elements in the plan; the curved shape of the High Street is unusual.)

Villages obviously must have started at some point in history, when a settler, farmer or soldier decided to clear a patch of land and build houses for himself and his followers. In most cases, we know nothing about the date or the nature of this act; in many parts of the countryside there is evidence that existing settlements can trace their origins to Iron Age times. Whether this is true for the wooded area that existed in the vicinity of Highley and surroundings is not clear. However, we can sometimes use the plan of the village to infer something about its history, even in the absence of any written records or archaeological digs.

The village plan is, as the name suggests, the way the old buildings such as the church and houses relate to each other and other features in the landscape such as roads or streams. Classically, there are several forms that can be recognised. In some cases, the buildings seem to be clustered around an open space; a village green. Sometimes the village is strung out along a road; the “linear settlement”. In other places, the houses and farms are so scattered that there is no discernible pattern. With luck and imagination, it may be possible to make sense of the plan. Sometimes it seems that a single individual was responsible for the layout of the village; at other times the community must have grown without any such central control.

Highley, in many ways, fits the pattern of a linear settlement, with the old houses stretching along the main road from the Manor House in the south, all the way up the High Street to Court House and Dowsley Cottage. Superimposed on this is a scattering of old farms and cottages in small clusters: Netherton, Borle Mill, Woodend and Woodhill. This of course ignores the more recent houses built after the start of mining, even though many of these are now over 100 years old. This suggests that the main centre of Highley was originally by the manor house and church; thereafter development was largely unplanned, with new hamlets or farms appearing randomly in the waste land of the parish in the early middle ages, whilst the main village grew up along the main road leading north. It is possible that there are the faint traces of an older arrangement still embedded in the landscape. The church and the manor house are diagonally opposite each other; the main road and Church Lane form two sides of a possible square. It is possible that the very earliest village was laid out around a green which subsequently was turned into normal fields. Whilst we may probably never know for certain, the distance between the church and former manor house is intriguing.

Chelmarsh provided another example of an interesting village plan. Here the church is adjacent to Chelmarsh Hall. However, there is then a distinct pattern of small fields and interconnecting footpaths stretching north for about a quarter of a mile. Today this pattern stops a little beyond Manor Farm, but a map of 1631 suggested that it extended to where a cross once stood. This cross may be the one that now stands in the churchyard. The pattern of small regular fields and lanes suggests that many of these plots were originally designed for houses: houses which have either long since fallen down or which were never even built. There are many precedents in the Middle Ages for ambitious lords engaging in what amounted to speculative building, trying to turn a small settlement into a new market town. Chelmarsh may have been one of these. Chelmarsh and Highley both belonged to the powerful Mortimer family in medieval times; perhaps we can still find evidence in their layouts of how it was once hoped that these villages would develop?

Catsley New Town?

Some of our local towns and villages have grown “organically”; they have arisen naturally as a small cluster of houses has grown, without any outside interference. Highley is a good example of this. On the other hand there are the “planned” towns and villages, where an outside owner has deliberately built a large number of houses to create a new settlement or expand on older one. Bridgnorth is a good example of a planned town on the equivalent of a green field site; in its present form it dates from around 1100 when the castle was built. Cleobury Mortimer, although an important centre in Anglo-Saxon times, was extensively redesigned at a similar period when the Mortimer family made it their administrative centre. Not all planned towns took off; efforts to establish a market at Stottesdon in the 13th century failed.

In the Public Record Office in London there is an account of Earnwood, written in 1565. Earnwood is the east part of Kinlet; it originally included a large amount of the Wyre Forest as well as farms and a cluster of cottages. Up until the end of the 16th century, it was considered separate from Kinlet and was a manor in its own right. The 1565 account includes a list of rents that the inhabitants of Kinlet paid for their land. Several are recorded as paying 12d for “burgages”. A burgage is the name given to a plot of land, usually with a house or a shop built on it, in a medieval town. The person who rented the land, the “burger” was given freedom from a whole range of other taxes and services that his rural equivalent would be expected to pay. The person who founded the town and gave out the burgage plots for rent would hope that by attracting entrepreneurs to the town, it would prosper and pay him more in tolls and taxes than he would get if he had left his land for agriculture. As noted above, this was a gamble that did not always come off and there are hundreds of villages and hamlets that once had urban pretensions in the Middle Ages. One of the clues comes from references to “burgages” in old documents. Thus there is evidence that at one point, somebody had desires to found a town at Earnwood.

There is one more piece of evidence that there might once have been a town planned for Earnwood. Opposite Catsley turn, where the roads join from Kinlet and Cleobury to go to Bewdley, there are two fields which, in the 18th century, were called Great and Little Philippatown. The –town ending might be significant.

In the Middle Ages, Earnwood belonged to the powerful Mortimer family. In the mid-14th century, the head of the family was Roger; his wife was Philippa de Montacute. Roger died in 1360 leaving Philippa to face widowhood. As was usual, provisions had been made to support Philippa if she did not marry again. She was given many of the Mortimer estates in Worcestershire; income from these would provide for her. She was also given Earnwood. It was as well she was given these estates, as she lived for another 22 years. It is highly unusual to find towns being established in the second half of the 14th century, but in 1376, Philippa did just that when she gave Bewdley its first known charter. Could the Philippatown fields preserve the memory of another attempt to establish a town by Philippa, perhaps before she settled on Bewdley?

There may be other explanations for the “burgages” in the accounts and the field names may be a coincidence. It is difficult to imagine why anyone should want to start a town on the Catsley turn and I have some doubts whether the site was even in the medieval manor of Earnwood. However, next time you drive past, perhaps you can be forgiven for imagining the ghost of a medieval estate agent trying to sell vacant building plots!

The Domesday village of Highley

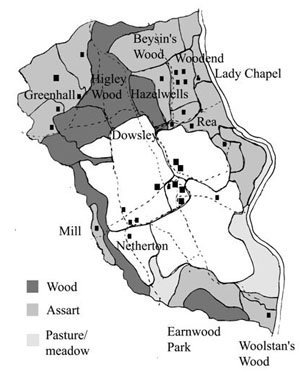

(This map shows a speculative reconstruction of land use in Highley at the time of the Norman conquest.)

(This map shows a speculative reconstruction of land use in Highley at the time of the Norman conquest.)

For many places in England, the Domesday Book is the first time they are mentioned. This is the case for Highley and it provides a unique snap-shot of the village at the time of the Norman Conquest.

The Domesday Survey dates from 1086; it was essentially a tax survey. William of Normandy had claimed England as his kingdom after the Battle of Hastings 20 years before, but nobody could agree on how much revenue he could claim in taxation from his subjects. The Domesday Book was produced to answer that question: it was designed to tell the Crown exactly how much money they were entitled to. Commissioners were sent round almost every village in the country to find out who owned the land in that place and what it was worth. The survey looked both backwards and forwards, determining what state the manor had been just before the Conquest (“In the time of King Edward”), what it was worth now and what its future value could be.

Highley was assessed for tax on 3 “hides”. A hide was nominally a unit of land which could be taxed. Its precise value varied from 60 to 120 acres. This would suggest that something like 300 acres in Highley was cultivated. The village is about 1500 acres which indicates that substantial amounts were either grazing or woodland. In fact Domesday records enough woodland to fatten 36 swine although it is far from clear how big this would be. The village population consisted of 6 farmers, 6 smallholders and one official called a “radman”. The farmers would have held substantial acreages in the common fields that surrounded the village. The smallholders would have been less well off with smaller holdings. The “radman” was an official who had to ride out of the village on the lord’s business and he may have had military duties. Allowing for the families of these men, the total village population would have probably been about 60 people.

The villagers would have shared their land in common fields and jointly had enough work to occupy 2.5 plough teams. Not all the land in the village was worked by the villagers on their own behalf; the lord also worked land for himself which required another 1.5 ploughs. No doubt the villagers were expected to look after the lord’s land as well as their own. The plough teams would each have been made up of 8 oxen and these would have been able to plough about 100 acres a year; in rough agreement with the guess of about 300 acres cultivated from the hidage.

Before the Conquest, Highley had been owned by the Countess Godiva and had paid her 15 shillings a year. Godiva held much land in Shropshire including Chetton; Highley was one of her smaller estates. Whilst she may have occasionally visited it, the radman may well have looked after most of her interests. Like many Shropshire villages Highley suffered immediately after the Conquest when its value went down to 3 shillings; perhaps it was caught up in the unrest that characterised those times. William gave Shropshire to Roger de Montgomery who in turn gave many manors including Highley to Ralph de Mortimer. By 1086 the manor had recovered and was worth 18 shillings although the Domesday commissioners felt there was enough potential arable land for another 2 ploughs. The Mortimers, no doubt, were soon busy bringing that land into cultivation. The Mortimers were one of the great baronial families of Medieval England; besides giving their name to Cleobury Mortimer, their early stronghold they also eventually produced an heir to the English throne.

The woods of Highley

(This map is a speculative reconstruction of land use in Highley at the end of the Middle Ages.)

(This map is a speculative reconstruction of land use in Highley at the end of the Middle Ages.)

Woodland features large in the early history of Highley. The village name means “the (woodland) clearing of Huga”. This shows that in the 8th or 9th century, when this name was probably first established, the village was surrounded by thick woodland. By the time of the Domesday Book, the wood was described as sufficient for the upkeep of 36 swine. This gives an insight into one of the functions of woodland; it was an area where animals could graze. In most medieval manors, the tenants had the right of “pannage”, to allow their pigs to eat acorns in the wood. It is not clear what sized wood would be needed to keep 36 swine (presumably the rather precise figure of 36 reflects an original estimate of “three dozen” which became formalised when written up for the Domesday survey!). There are some surveys from Worcestershire which suggest that this would be an area of about 150 acres. This seems rather low for the total area of woodland in Highley, which was probably two or three times the size at this date. However, woodland had various uses, including the hunting of game, and perhaps the villagers were only allowed access to a proportion of what actually existed.

In the centuries immediately after the Norman Conquest, the woodland in Highley must have come under considerable pressure. The population increased and more land had to be brought into cultivation to feed it. Domesday Book anticipated this by noting how something like 150 acres of marginal land, probably rough grazing, could be cleared and turned into arable. In the event, probably two or three times this was eventually cleared. Just occasionally we can get glimpses of this; in about 1230 one of the chief landowners in Highley, William de Wootton, granted 3 acres of wood to the Hospital of St Wulstan’s in Worcester. This was at Brook’s Mouth, where the holding soon grew to 30 acres. Until the 19th century this was known as Woolstan’s Wood. The Hospital appears to have cleared the land and perhaps turned it into pasture or meadow, before subletting it to tenants. This process of granting woodland to create new farmland was called assarting and many of the village farms such as Hazelwells or the Rea seem to have originated in this way. Woodend Farm tells its own story; marking the point when it once stood on the boundary of a wood that extended north to Hampton Loade.

The woodland in the village belonged to the Lord of the Manor. When he allowed an assart, the farmer would have sole rights over the newly cleared land; in return he would pay a rent to the Lord for his new estate. Whilst this worked both to the benefit of the farmer and the Lord, it was not such good news for the rest of the village. The newly cleared land would no longer be available to them for grazing or for firewood. For the smallholders, these rights were very important. Thus there was considerable pressure to retain some woodland for common grazing. By about 1500, something like 140 acres of common woodland remained in the village, known as “Higley Wood”. (It may not be a coincidence that this is roughly the same size as the land allowed in Domesday for the village swine). This was located in the north of the village, roughly on the land now occupied by Garden Village. In 1603 it was still in existence when it contained 3200 oaks. However, shortly after that, economics finally won through; the land was divided between the major farmers in the village in plots of about 5 to 10 acres. These enclosed their holdings, felled most of the trees and the last of the common woodland of Highley vanished.

Field Names

Many people will be aware that almost every field once had its own name. We are fortunate in Shropshire that a local historian called H. D. G. Foxall has produced maps of every parish in the county showing these names as they existed in the middle of the nineteenth century. These are available from the Records Office in Shrewsbury; a copy of that for Highley is in the library. Foxall transcribed the Tithe Maps. The reason why these were drawn up need not detain us here (I am not sure I really understand the reason myself…); what is of interest is the nature of the field names themselves. Foxall published a short guide to Shropshire field names and I have used this extensively when looking at Highley.

Some of the names in Highley are fairly mundane. There are three “Little Squares”, accurately describing their shape and size. There are two “Severn Meadows”, two “Upper Meadows” and three “Lower Meadows”. Geographical features are very often mentioned; numerous fields are called banks of some description; “Banky Piece”, “Broomy Bank” and so forth. A less obvious version of this is “The Yells”, a field alongside the brook between New England and Borle Mill. This is first recorded in the sixteenth century as the “Helde”. Helde is an Old English term for a slope, an accurate description of the steeply sloping Borle valley. Many will be familiar with the patch of common on the Brown Clee called “The Yelde”, which comes from the same root. Another less obvious name is “Cromwells”, a field that bordered the small stream rising in Netherton and which runs into the Borle Brook by Westpoy Construction. The most likely origin of this name is from the Old English, crumb, meaning twisted. The stream twists and turns a lot at this point, so the field boundary is very irregular.

Many names reflect old agricultural practices. There are a number of names that include the element meadow, pasture or orchard, indicating their use. Leasow is very common. This can simply be pasture, but it may specifically indicate land that was once ploughed but had subsequently been turned over for grazing, particularly after the enclosure of the open fields (c1620 in Highley). An echo of the large, open medieval fields is “The Butts”. Again found between New England and Borle Mill, this is land where the team of oxen used to turn when pulling the heavy, wooden medieval plough. By Wren’s Nest were a series of thin, narrow fields called “The Pikes”; these were some of the original strips that individual farmers held within the open fields. Highley was of course originally heavily wooded and this is reflected in many names. “Stocking”, found between Rhea Hall and the river, indicates land cleared of trees (the name actually comes from the tree stumps). Numerous fields are named after individual trees: Walmer Meadow, now the site of the Country Park Halt refers to the alders which still fringe the riverside.

Another common class of names refer to buildings or features close to the field. There are many Barn fields; House Fields are normally adjacent to the farm house. Long vanished quarries, coal pits and brick-kilns have given several fields their names. In some cases entire farms are simply represented by a field name. Nether Hall must have been an imposing building in the sixteenth century; by Victorian times it was just a field name, opposite what are now the Old Colliery Offices.

Whilst the tithe map is very valuable, it is simply a snap-shot of field names in Mid-Victorian times. Deeds from the seventeenth century usually reveal very different names. Equally, names familiar to me such as Stony Stile, Hag Leys and the Murder Field (all by Hag Farm) are not mentioned on the Tithe Map. With the advent of large scale maps where each field is numbered, names are no longer used for official purposes. However, while people still have to work in fields, they will continue to find names for them.

Bits of pots…

From time to time, I can be seen walking slowly across fields staring intently at the ground. This is not (always) because I am trying to ignore other people, but is because I am fascinated by bits and pieces of old pottery that occur in some areas and what they can tell us about past times.

As anyone who has ever watched a TV archaeology program will know, bits of pots are invaluable for archaeologists when trying to date sites. When archaeologists dig, they are particularly interested in looking for bits of pots (sherds, to use the jargon) that are buried in the ground in the same layers as the object they are excavating. When this happens, it means that the pottery and the object were buried at the same time and the pottery can be used to date the site. This of course is why pottery is so useful; it can usually be dated with some precision, as different ages used very distinctive forms of pots. Excavating sites is of course, a very skilled business best left to those who know what they are doing. By contrast, a second way of using old pottery is less technically demanding. Bits of pottery that are found on the surface, or thrown up by shallow digging or ploughing, have lost the context in which they were buried. However, the presence of large quantities of old pottery can be used to pinpoint the sites of old houses and the type of pottery that is found can give a rough guide as to the date of the house.

The type of pottery most familiar is probably the “blue and white” ware, or “Willow Pattern”. Of course, this is still being made and so it is not necessarily of any great age. However, it has been in common use for over 200 years and is common around houses that were occupied in the 19th century. Just as common is plain white or cream ware; here the shapes of the broken cups or plates can sometimes provide a date. On one occasion a fragment of a white cup I found could be dated by its handle to the 1820s.

Going back further, white becomes rare. Most older pottery was made of reddish clay, obvious when broken. This may however, have been covered in different coloured glazes. Perhaps the most distinctive pottery of the 18th and late 17th century is slipware. Typically the surface of a plate would be covered in either a yellow or black background. On top of this a swirling pattern would then be made with a different coloured substance (the “slip”). The underside of the plate would be left unglazed. Plates also often have distinctive “pie-crust” edges. Slipware was made both in the potteries and around Jackfield and Coalport; it is both unmistakable and beautiful. Brown and black glazes are common on pottery from the 16th-18th centuries.

Although not strictly pottery, fragments of clay pipes are also common, particularly the stems. However, the bowls are best for dating. They are always made of white clay.

In medieval times, the most common glaze used on pottery is a greenish-yellow. Other pots were not glazed; generally the less spectacular the piece of pottery, the older it is! The oldest piece of pottery that I have been shown that has been found locally is a small piece of Roman “Severn Valley” ware; red but with traces of blue in the middle. Earlier pottery will be very rare, but bits of flint sometimes turn up to represent prehistoric times.

Next time you are out walking, look out to see what you can find. If you do come across any interesting bits of pottery, do let me know!

The Four Parishes Heritage Group; what are we doing? (1)

(This article was published in the ‘Highley Forum’ in April 2006.)

Three months ago, I reported on a newly formed local history group called the Four Parishes Heritage Group. We are researching the history of our local area. The four parishes in the title refer to Highley, Kinlet, Billingsley and Stottesdon, but we do not have any firm boundaries and will quite happily look at other parishes such as Farlow, Chelmarsh or Middleton Scriven! We have recently been awarded a grant of £23,500 from the Local Heritage Initiative (LHI). The LHI is a national grant scheme that helps local groups to investigate, explain and care for their local landscape, landmarks, traditions and culture. The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) provides the grant but the scheme is a partnership, administered by the Countryside Agency with additional funding from the Nationwide Building Society.

Our project is about the early iron industry in our parishes. Most people will know that we sit on the Wyre Forest Coalfield. Large-scale mining started in the 19th century and reached its peak in the 1950s when over 1000 men worked at Alveley Colliery. However, coal was worked on a smaller scale for many years prior to that. The earliest reference we have is in 1595, when coal was being mined in Chetton by Thomas Hord, a prominent citizen of Bridgnorth. It is possible that coal was being dug at earlier periods but the records are silent about this. Whilst there are numerous remains of early coal mines (so-called “bell-pits”), these are very difficult to date and they were used until the 19th century. Thus looking for earlier evidence of coal mining is a very difficult task.

Fortunately, we can take another approach. Coal is found with ironstone. At the later local mines, the ironstone was a nuisance that was thrown away. However, in earlier periods it would have been valued in its own right; indeed if we go back far enough, it would have been more important than the coal. In the woods around Chorley and Billingsley, there are shafts surrounded by lumps of ironstone. We have no records of ironstone being mined until the 18th century and ironstone mines are as difficult to date as coal mines. However, ironstone is, by itself, of no use. It needs to be turned into metallic iron and until the early 19th century, this was usually done close to where it was mined. When ironstone is converted to iron metal, slag is produced as a waste product, and this tells us a lot about the way in which it was done. In the 19th century at Billingsley there was a coal-fired blast furnace; this produced a glassy blue-grey slag. From the 16th-18th centuries there were a number of local blast furnaces that used charcoal (made from wood) rather than coal as a fuel; they produced large amounts of a glassy green slag. However, in the woods of Billingsley and Chorley another type of slag is found; this is dull blue, metallic-looking and full of bubbles. This type of slag comes not from a blast furnace but a bloomery. In a bloomery, ironstone was heated with charcoal. This produced iron metal, but it never melted; instead it formed a spongy mass in the bottom of the furnace (a bloom), sitting in a pool of molten slag. The bloom would be taken out with tongs and hammered to expel the rest of the slag and produce a bar of what was effectively wrought iron, ready for use by blacksmiths. The most interesting point about bloomeries is that locally they stopped working around 1570, after the introduction of blast furnaces. Thus we have evidence of a thriving local iron industry, pre-1570 (and probably medieval), before our first records of coal mining. In our project, we want to find out more about this early industry. If anyone in interested in our work, please contact me.

David Poyner – email: David@D-Poyner.freeserve.co.uk)

The Four Parishes Heritage Group; what are we doing? (2)

Last month, I wrote an introduction to our group. We are interested in the history of Highley, Stottesdon, Billingsley and Kinlet (although we are also happy to cover adjacent parishes such as Chelmarsh and Glazeley). Very recently we have been awarded a grant of £23,500 from the Local Heritage Initiative (LHI). The LHI is a national grant scheme that helps local groups to investigate, explain and care for their local landscape, landmarks, traditions and culture. The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) provides the grant but the scheme is a partnership, administered by the Countryside Agency with additional funding from the Nationwide Building Society. We will be using this money to look at our area in the middle ages, particularly to understand how the countryside was shaped by the local iron industry.

We know in the woods around Billingsley, Chorley and Kinlet, ironstone was being mined and turned into bars of iron. This production of iron was done at furnaces called bloomeries. We can identify these because of the waste slag that they create; large piles of this still survive. We know of two particularly well-preserved sites, one between Billingsley and Chorley in the Deserts Wood and the other between Rays Farm and Kinlet. Both of these lie on streams and this is no coincidence. We think that the water was used to power bellows and work hammers. At a bloomery, the ironstone was heated with charcoal until it became hot enough for the impurities to melt. These could then be drained off. However the iron itself never properly melted, instead forming a spongy mass in the bottom of the furnace. This was removed and was hammered until it formed a wrought iron bar called a bloom. This could then be used by blacksmiths.

Although we know the approximate sites of our two ironworks, we really have little idea about how exactly they worked. We do not know where precisely the furnaces were or how the bellows and hammers were worked by the water. It is possible that the water-powered bloomeries that we can now see were originally worked by hand, but this needs to be investigated. We do not know who owned the bloomeries or what quality of iron they produced. Perhaps the biggest gap of all is that we do not know when the bloomeries worked. A small amount of medieval pottery has been found on the two sites, but that is only of very limited use for dating the works.

The project will try and answer these questions by mapping the surviving earthworks and carrying out geophysical surveys. Devotees of TV archaeology programmes will know all about “geophys”. By measuring differences in electrical and magnetic fields, we can learn what is buried underground without ever having to dig. This is particularly important as our ironworks are in Sites of Special Scientific Interest and so our ability to excavate will be very limited. However, by using geophysics and by chemically analysing the slag we hope we can discover how the furnaces worked. Finally, to test our theories, we will reconstruct a bloomery and try and make our own iron.

The projects will cover much more than just the ironworks and I will write about other aspects next month.

The Four Parishes Heritage Group; history in hedges

More than anything else, it is probably the pattern of fields and hedges that most people think of as being typical of the countryside. Of course, in some parts of the country many hedges have disappeared, in response to the demands of large machines and changing farming practices. However, in our part of Shropshire hedges, although reduced in numbers, are still plentiful. The importance of hedges to the natural environment is well known; they are home to many plants and animals and increase the variety of wildlife in the countryside. However, they are also important to historians and archaeologists.

Back in 1970, Dr Max Hooper proposed that it was possible to date hedges by counting the number of species; each plant in a 100 foot length of hedge represented about 100 years. This relationship arose because in the area in which he was working, hedges were only planted with a single species; one new species would typically spread into a 100 foot section every century. There is no doubt that up to a point, this simple relationship works over large parts of southern England. However, within a few years it became apparent that there were other parts of the country where it did not hold true, including Shropshire. Here hedges were planted with a mixture of species and so the technique would not work, at least as Hooper originally proposed.

Back in 1996, a group lead by Dr Jan Ensum obtained funding to carry out a survey of hedges in Highley. They were able to hire a professional ecologist, Dr Ed Mountford, to co-ordinate the work and analyse the findings. A group of about 10 volunteers recorded not only the number of species but the type and features such as the number of gaps and the presence of trees and hedge banks. Almost 300 hedges were recorded; probably 75% of all those in the village. This remains one of the most comprehensive surveys of hedges within a single parish that has ever been undertaken.

The problem with recording 300 hedges (nearly 30 miles!) is that it generates a vast amount of data. Whilst Ed was able to produce a summary of the findings very quickly, the detailed analysis took several years, as it was necessary to research the history of each hedge so that could be correlated with the species it contained. As expected, Hooper’s rule did not apply; the hedges of Highley were extremely diverse.

However, it became apparent that it was possible to get a rough date for the hedge by other means. Two factors seemed to indicate medieval hedges. Those that were extremely species-rich (seven or more species/100 feet) all seemed to be very old. Secondly, several species, especially Lime and Wild Service, seemed to be restricted to very old hedges. These seem to be “woodland relic” hedges; formed by medieval farmers when they cleared natural forest to form the first fields in the village.

Based on these results, as part of the Local Heritage Initiative project, the Four Parishes Heritage Group will be recording hedges in parts of Kinlet, Billingsley and Stottesdon.

Pits and pools

As part of our history project funded by the Local Heritage Initiative, the Four Parishes Heritage Group have recently acquired copies of the tithe maps for Highley, Kinlet, Billingsley and Stottesdon. Tithe maps were drawn up around 1840 for virtually every parish in the country. They show every field, house, barn and road; furthermore, the name of each field is given. Thus they are a very useful resource for local historians, providing a detailed picture of the countryside at the start of the reign of Queen Victoria. In fact, many features that they show had probably been in existence long before the maps were drawn up and may indeed date from medieval times.

One striking feature of the Stottesdon maps is the number of fields with pools in them. Not every tithe map would be expected to show this level of detail; we are fortunate that the surveyor for Stottesdon was particularly diligent. Sometimes pools occur naturally, but in our part of Shropshire this is unlikely unless the pool is on a stream; the Stottesdon examples are well away from any watercourses. Pools can also be created for use of animals, but again, the Stottesdon pools seem too big for this.

A clue as to their origin is the fact that they lie in lines, close to each other. They seem to be following a series of natural features; almost certainly they were flooded quarries. Further support for this comes from the fact that a number of other fields that are close to them are called either “Pit field” or “Quarry field”. Indeed, final confirmation comes from the fact that in one of the Pit fields, an active quarry is marked.

Many of the pools and pits have been filled or ploughed out, but a few survive, as saucer-shaped hollows, typically about 50 feet in diameter and a few feet deep in the middle. By looking at the stone dug up by moles in these hollows, it seems clear that it was limestone that was being quarried. Limestone is found in a series of bands and the quarries follow these outcrops. There are virtually no written records to tell us about these quarries. Clearly some were at work when the tithe maps were drawn up and Stottesdon Chapel (c1840) has been built using stone from one of these.

We hope that we can discover more buildings and perhaps boundary walls that might have used the local limestone. However, much limestone was burnt in kilns and spread on fields as a fertiliser. We do not expect to find many surviving limekilns, but there a number of fields called “Limekiln Field” which show where they stood; if these are regularly ploughed, the kiln sites might show up as dark stains on the ground.

Whilst the best examples we have come across of these limestone quarries are in Stottesdon, field walking shows they are elsewhere as well. A series of shallow depressions can be seen from a footpath that runs by Crumpsend Farm in Kinlet; these are also almost certainly quarries. Interestingly, a hedge now runs through the middle of one of these, showing it must be several hundred years old. Some of these quarries may be very old indeed; some medieval accounts for elsewhere in Kinlet dating from 1373 refer to Limepit field.

It is possible that some of the Stottesdon quarries could be just as old. As we do more fieldwork and documentary research, we hope we might be able to discover more about this forgotten industry.

Tithe maps and old deeds

The Four Parishes Heritage Group is researching the history of Highley, Kinlet, Billingsley and Stottesdon. As I reported last month, we have acquired the tithe maps of our parishes, drawn up around 1840, which show the name and ownership of every field. However, we want to work back from the 19th century to medieval times and that requires a lot of detective work in various record offices, collecting information on how the parishes have changed. We have recently made a start in the Shropshire Record Office. A particularly useful set of documents are the deeds from the former Kinlet estate. At its height this covered not only Kinlet but significant chunks of many other parishes; thus it is an excellent place to start. The collection includes a number of medieval deeds. Making sense of these will be a challenge for us, but we are starting to make some progress.

One of the earliest deeds is from 1340 and is the sale of land at Catsley, in Kinlet from “Richard son of John the muneter of Wynton to Lord Richard Nowel and John de Adforton, cleric”. A muneter is an old term for a person who made coins; in medieval times coins were made by hand in a small number of mints. Wynton is a another name for Winchester, where there was an important mint. Thus we can learn from this opening line of the deed that somehow, part of Catsley belonged to a Winchester coin-maker called John. How this came about remains a mystery. However, in 1340 John’s son, Richard, decided to cash in on his estate and so sold it to Richard Nowel and John de Adforton. Adforton, the place where John came from, is a hamlet close to Wigmore in Herefordshire. This is signficant as Wigmore was the power centre of the Mortimers, the family who owned most of the land in this part of Shropshire, including Kinlet. We can speculate that John had entered into the service of the family and had risen through the ranks until he was able to buy land in his own right. Richard Nowel probably also worked for the Mortimers. His name features in other documents; he owned land elsewhere in Kinlet and was also park keeper of the Mortimer portion of the Wyre Forest. Essentially this meant that he was responsible for stopping poaching of game and illegal felling of trees. It could be a lucrative appointment and he seems to have been a shrewd businessman, investing in property where he could.

Catsley did not come cheap. It was sold for a little over £3. Most ordinary people would expect to earn around £5 a year so this was a considerable sum of money. However, that was not all; Nowel and Adforton also had to supply a pound of cumin. Spices such as this were luxury goods in the Middle Ages; they were seen as status symbols.

Today Catsley is essentially just one farm, but in 1340 it was more than that. Nowel and Adforton’s estate included 7 tenants, most of whom would have lived somewhere on Catsley. There are traces of earthworks in the fields around Catsley farm, perhaps the remains of the houses where these people lived. One of the tenants paid his rent not in money, but with a pound of cumin. No doubt Nowel and Adforton used the first year’s rent to pay Richard as part of the purchase money and in subsequent years used it to offer curries to their guests! Two of the tenants not only paid a monetary rent; they “came with their bodies and everything else”. These were “customary” tenants; they were legally bound to the estate and were included as part of the sale. Whilst they would have had small farms of their own, they would have been expected to work unpaid for the owners of the estate.

By studying deeds in detail like this, we can learn a lot about life in medieval times.

Heath

We live in a man-made world. This is as true in the middle of Shropshire as it is in the centre of Birmingham; the “natural” environment that is all around us is a product of human intervention. For farmland, this might seem obvious, but our woods have equally been influenced by human activity; the oak and ash trees that are now so abundant owe their predominance to the work of past foresters. Whilst it is commonly thought that woods have declined, at least in term of acreage, this is untrue; I suspect we probably now have more woodland than at any period from the Middle Ages. However, other habitats have suffered, perhaps none more so locally than heathland.

A heath is essentially an overgrazed wood on a poor soil. Heavy grazing stops trees from taking over; the poor soil means that dense turf cannot form. What happens instead is that bracken and shrubby plants like gorse or heather predominate. Heaths rarely form naturally; they require constant grazing to keep trees or coarse grass at bay. They can be regenerated by burning, a form of management that is sometimes used. There is of course plenty of heath-like vegetation on top of the Clee Hills; however, this is better considered as moorland, rather than the lowland heath being considered here.

Heaths were once an important resource. They provided a useful source of pasture for animals, who could feed on the patches of grass that did exist or browse plants such as heather. Bracken had a variety of uses, including thatch, bedding for animals and for insulation. Plants such as gorse or heather were important fuels; they burnt quicker and more intensely than wood and were particularly useful for jobs such as heating baking ovens. Thus, once established, the heaths became as important as the local woods and commons in the life of medieval villages. However, changes in farming in the 17th century meant that areas of common grazing became enclosed into private fields; once this was done, heaths were usually ploughed up or converted to conventional grassland. Furthermore, with the demand for charcoal and other woodland products, many landowners found it equally as profitable to return their heaths to woodland. The last area of large heathland to exist locally was probably Sturt Common in Kinlet, that until the Second World War was an open area covered in gorse. Today there are still small areas where fern and gorse predominate, but they are scattered amongst woodland and scrub.

If lowland heath is greatly reduced today, we can still at least trace its former extent. This can best be done by looking at place names. In Highley, the Heath Farm, a name first recorded in the 17th century, stood close to the River Severn and is now part of Coombey’s Farm. It seems that this was an area of heath that linked the woods that still survive alongside the Borle Brook with those by the station at Stanley. By Hag Farm, there was an area of about 25 acres called Heathy Leasow, again, a name first recorded in the 17th century. This may once have been a heath connected with Higley Wood, the village common that was roughly where Garden Village now stands. Elsewhere, the fieldnames “Gorse Furlong” and “Broomy Bank” are reminders of lost heath.

In Chorley, on the borders of Billingsley, is Chorley Covert. This was once known as Common Heath; a name that is self-explanatory. On the west of this in the 19th century was a field called “Hadilye”. This is probably from Old English and means “heath clearing”. The name suggests that this part of Chorley had been heathland in the earlier part of the Middle Ages, perhaps even in Saxon times.

This work was carried out by the Four Parishes Heritage Group on a project supported by the Local Heritage Initiative and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Nationwide Building Society.

Dingle Lake

Middleton Scriven is a small village, hidden down a warren of narrow lanes. It is easy to think that it has always been a sleepy hamlet; a typical example of rural England. However, half a century ago, it was the place to go clubbing, attracting people from as far away as Birmingham.

The story of Bridgnorth district’s most unlikely night club started in the late 1930s. In the north of the parish was an area known as the Dingle: a wooded valley, steep sided in places but opening out further upstream. It was there that a Black Country businessman, Mr Brewster, had a vision. He built a substantial concrete dam across the stream to create a lake. At the far end of the lake he built a bar and clubhouse. He set out a drive and walks around the lake. A generator discreetly installed in a remote corner of the site provided electricity so he could illuminate the lake with coloured lights. Then he began marketing his creation as a venue for dances, whist drives and general entertainments. Perhaps it was the novelty of the situation or simply the quality of the entertainment (coupled with Mr Brewster’s marketing skills), but the venue soon established itself as an excellent place for a night out.

Dingle Lake was managed for Brewster by a Mr Ling. He worked with Herbert and Phyllis Turner to organise the dances; the Turners were very good dancers themselves and this must have helped the place establish itself. The dance was one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the 1930s; it just required a few musicians, a big enough room and a suitable MC to co-ordinate things. Whilst Dingle Lake was off the beaten track, a large field next to it provided plenty of parking and, in the 1930s, the private motor car was just starting to establish itself locally. There was always the bicycle for those without cars and as Dingle Lake became more established, coach parties were organised to visit it. I have been told that a few wealthy socialites would occasionally even fly from Birmingham, landing a light aircraft in the field next to the Lake.

On arriving at the Dingle, the party-goers would walk past the lake, lit up by lights in the evenings, to reach the clubrooms. There were two huts. The first housed snooker and billiard tables, as well as living accommodation for the manager, with a bar behind. There was then a short walkway leading to the second hut, which was the dance hall. This could be adapted for other events such as “Fur and Feather” whist drives (with game or poultry as prizes).

Dingle Lake was not just for evening entertainment. During the day the snooker and billiard tables would be available for use and it was possible to walk around the grounds. There was a boat that could be used for trips around the lake; latterly this is remembered as the “Iron Duke”, an ex-army craft. Photos taken around 1940 also show a chalet by the side of the lake; suggesting that it could be hired for holidays. There was a children’s play area next to the club room.

Dingle Lake prospered throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. It featured in an article in the Bridgnorth Journal in the 1940s and many local people recall visiting to attend the regular dances. However, as the 1950s drew out, the traditional dances and whist drives became less popular. More practically, the lake itself was silting up and so eventually the venue closed. Today the site is a nature reserve, but the dam and the bases of some of the buildings survive as remainders of its most un-natural past.

This work was carried out by the Four Parishes Heritage Group on a project supported by the Local Heritage Initiative and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Nationwide Building Society.

Dingle Lake continued

About two years ago (in 2007), I wrote a short article on Dingle Lake in Middleton Scriven. Dingle Lake was the site of a social club that flourished from the 1930s until the end of the 1950s. As its name suggests, it was set beside a lake; at the far end was a clubhouse that hosted dances and other events. Despite its location down a narrow lane far from any main road, it was a very popular spot. Not only did it attract local people, it also had a following from as far away as Wolverhampton.

Since I wrote the original article, more information has come to light. In particular, two of the grandsons of the original owner of the lake, Eric Jenkins and Philip Bennett, have worked together to record their memories of the venue. They have been presented to the local parish council and I have drawn on them to write the current article.

The Dingle Lake Social and Sports Club was founded by Charles Brewster in 1930 or 31. Mr Brewster had a number of business interests and was also a bookmaker who lived in Wolverhampton with his wife. It is not clear whether he originally set out to establish a country club or whether he was simply looking for a pond for private fishing; he was a keen angler and also had shooting rights on various estates. He thought about establishing his fishery near Worfield until he was told about Dingle Lake, apparently whilst having a drink in the Halfway House Inn near Bridgnorth.

Whilst the existing lake was somewhat the worse for wear, he obtained a lease from the Bunney family, repaired the dam and stocked the site with fish. Possibly as a result of demand from his angling friends, he realised the potential of the site and so enlarged or rebuilt the existing buildings and obtained a private members’ drinks licence. In addition to the clubroom, there was a chalet built overlooking the lake; this provided sleeping accommodation for visitors. A canoe and a punt were available for trips on the lake. A local man, Hughie Bunney, was the caretaker. Electricity came from a generator and Hughie apparently brought drinking water to the site in buckets.

Before the war the site was very popular, particularly with a number of players from Wolverhampton Wanderers. They in turn would have raised the profile of the club, bringing in their friends. It also seems that business associates of Mr Brewster used Dingle Lake for works outings; there were regular coach parties from Courtaulds in Wolverhampton. During the summer it seems that members of the Brewster family and their close friends would stay on holiday at Dingle Lake, sleeping in the chalet or camping.

Mr Brewster died in 1942 and the lease of the club was transferred to one of his close business associate, Hubert Ling. Mr Ling was a locksmith in Wolverhampton and he seems to have helped Mr Brewster with the management of Dingle Lake. The club may have struggled for a period as there are recollections of the lake silting up, but it appears to have regained its popularity for at least a period in the 1950s. One story that has come to light is of a coach outing from Wolverhampton in about 1958. After heavy rain, the field that was used as a car park was a quagmire; unfortunately the coach driver failed to realise this and got stuck. The party spent the night in the clubhouse and the coach was eventually pulled out by a tractor the next day. Dingle Lake finally closed in 1959/60 when Mr Ling retired to Hampshire. By then, maintenance costs were becoming heavy.

I am sure that there are many more stories about Dingle Lake; I would love to know more!

David Poyner – email: David@D-Poyner.freeserve.co.uk )

Archaeology from the air

Devotees of Time Team and similar TV programmes will be aware that no archaeological investigation is complete without a trip up in a helicopter to view the dig from the air. From above, it is possible to get a completely different view of a site; no matter how carefully it has been planned or mapped, it is always worth checking out the aerial view to see if anything has been missed. Particularly when the lighting is right, shallow earthworks stand out as shadows and a whole new landscape can be revealed. Also visible from the air are cropmarks and allied features. Buried walls or ditches can cause crops to ripen at different rates from those around them; these then show up as dark or light patches in the field. In exceptional circumstances it is possible to discover the plan of a whole complex of buildings. Crop marks work best with deep-rooted crops but in very dry weather it is possible to see parch marks even in fields of grass. Ploughed fields can show soil marks, where the archaeological site has caused a change in soil colour.

The problem with aerial photographs, of course, is that they need to be taken from the air; unless you own a plane or a helicopter, this is a major problem. Consequently, it is usually necessary to rely on photos taken by others. Today it is possible to view aerial photographs of virtually any place in the country on publicly accessible websites such as those provided by Get Mapping or Google Earth. These are always interesting and sometimes can be of real value. However, the publicly accessible images are of low resolution and this frequently makes interpretation difficult.

The National Monuments Record (NMR), based in Swindon, is a public database of high-resolution aerial photographs, now operated by English Heritage. They hold a vast range of photographs; typically any part of the country will have been recorded several times from the air from the late 1940s. There is an element of lucky-dip about the photographs that they hold; it is necessary to order by reference to a map and either wait for copies to be posted or visit the office in person. However, the process is often worthwhile. In particular, the photos from the late 1940s to the early 1960s show a host of features in the countryside that have now been eliminated due to more intensive agriculture. However, even the later photographs can still show interesting crop-marks.

As part of the Local Heritage Grant, the Four Parishes Heritage group have been using photos from the NMR collection. Early on these showed a small oval in the north-east of Stottesdon; this almost certainly marks the site of an iron-age or Roman farm. More recently, further examples of these have come to light in photos around Chorley. A fascinating photograph from Billingsley taken in August 1981 shows a pattern of rectangular lines, which correspond to hedges shown on Victorian maps of the parish. However, beneath these again there is a roughly oval feature which may be another Romano-British farm. It will be necessary to carry out field walking to confirm the identity of this feature. Elsewhere, photos from the 1990s show up medieval plough marks (ridge and furrow) particularly clearly. It is not just very old features that show up in aerial photographs. In Billingsley, the remains of an early 19th century tramway can be traced on photographs. In Kinlet the US army bases from World War II have revealed their details and in Highley it is even possible to trace the plan of a sewage works at New England, built in the First World War to serve Garden Village and abandoned around 1950.

This work was carried out by the Four Parishes Heritage Group on a project supported by the Local Heritage Initiative and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Nationwide Building Society.

LIDAR, or what’s beneath the Wyre Forest

The history and archaeology of the Wyre Forest in Shropshire and Worcestershire is being studied as part of a new project “Grow with Wyre”, being funded by the National Lottery and led by the Forestry Commission.

Woods look deceptively changeless. However, as one of the pioneers in historical ecology has memorably written, a wood is simply a field that has not been cultivated for a generation or more. Left to itself, any patch of land will eventually become covered with trees. This can easily be seen by walking around the parts of the Severn Valley Country Park that were part of Alveley Colliery in 1969; today many are covered in birch trees, with oak and ash now establishing themselves. There has in fact been a constant movement of woodland boundaries, as land has been cleared and then abandoned, with the cycle repeating itself many times over the last two millennia.

From the point of view of archaeology, woods are places of high potential. As they have usually originated from land being abandoned, the remains of previous activities have usually not been deliberately destroyed but simply left to decay. This means that there is a good chance of being able to detect them. However, there is one problem: trying to spot the archaeology between the trees. Even in the open, it can be difficult to make sense of the lumps and bumps that are the hallmarks of so many archaeological sites; in a wood it is so much worse. Archaeologists frequently make use of aerial photographs to make sense of their sites; a random array of humps can often show a pattern when seen from above. In woodland, this is almost always impossible; with conventional photography all that can be seen are the tree tops.

LIDAR is effectively a new way of taking aerial photographs using a laser, which can penetrate beneath the branches of the trees. The technique works something like radar; the light beams pass between the branches, bounce back off the ground and are detected by a plane. Then, with tens of thousands of pounds of computer software, these signals can be processed to give a type of photograph.

A LIDAR survey was recently undertaken of the Wyre Forest. The full results will not be ready until October, but already the preliminary data is very interesting. Perhaps the most exciting findings are the discovery of what seem to be two iron age or Roman farmsteads, one in Arley and the other in Kinlet. Indeed, the Four Parishes Heritage Group have found a lot of Roman pottery in the Kinlet area, suggesting that there was a lot of occupation in those days. It seems that, as part of this, parts of the forest had been cleared for farming. Following the Roman period, the population collapsed and did not recover until the Middle Ages, when again the forest was cut back. Sure enough, the LIDAR has discovered evidence of medieval ploughing beneath the trees, again in parts of Kinlet. This also fits in with what we in the Four Parishes Heritage Group have been able to discover from documents.

It will be of great interest to see what more is discovered when the LIDAR survey is complete.

The Four Parishes Heritage Group are supported by the Local Heritage Initiative and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Nationwide Building Society.

Place names

Some time ago, I wrote about how the names of villages, hamlets and sometimes even individual farms, can tell us about the past appearance of the landscape. Most of our villages acquired their names in the Anglo-Saxon period. The Saxons frequently named these places after prominent features in the surrounding country-side. Sometimes these names are not particularly informative. Faintree, close to Neenton on the Bridgnorth-Ludlow road, means “multicoloured tree”. Whilst this was no doubt a striking botanical oddity, it does not say anything about the wider landscape. However, other names are more useful.

Many names end in –ley. This is usually an indicator of woodland; at the time when villages were named, ley normally indicates a woodland clearance. Thus Highley, Billingsley and Glazeley point to a northwards extension of the Wyre Forest in Saxon times. When studying place names, it is often very difficult to work out the meaning of the first part of the name; traditionally scholars have assumed that these were personal names. So Billingsley was the clearing of a man named Billing and Highley (which is spelt Hugesley in some early documents) was the clearing of a man named Huga. There is now a move away from this. Some time ago, it was noted that “Bill” is Old English for a sword (as in billhook) and so Billingsley may mean “the clearance shaped like a sword”. More recently, it has been suggested that “Hug” may have meant a steep hill or a ridge. This would certainly fit the site of Highley and would also be a suitable explanation for Higford, a hamlet near Worfield and the only other place in Shropshire which begins in “Hig”.

Place names can help us understand the develop-ment of villages. In Highley, Netherton means “the lower settlement”; that description only makes sense if it was founded after the original village was established. Thus it seems that Highley was the name of the first village in this parish, around the church and Netherton was settled later. Equally Woodend Farm, now in the middle of fields, speaks of a time when woodland was much more extensive in the north of the parish.

Kinlet means Royal Portion; it may have originally belonged to the Anglo-Saxon Kings who used it for hunting in the Wyre Forest. Norton’s End, in the north of the parish tells a similar tale to Netherton in Highley; Norton means the “north settlement” and it was obviously established after the main village of Kinlet. In the south of the parish are a series of farms that sound as though they were named after individuals; Catsley, Meaton, Button Bridge and Oak, and Winwood. In the case of Winwood, this has support from one of the oldest surviving documents that is relevant to Shropshire. This is an Anglo-Saxon charter, nominally of 994, which describes the boundaries of Upper Arley. These followed the modern parish and so it is possible to trace the boundary as it runs along the Bewdley road through Button Oak and then turns towards the river Severn at Winna’s tree. This Winna must surely be the same individual who gave his name to Winwood Farm; the tree would have marked the corner of his land where it came up against Arley. It is possible that the south of the modern parish of Kinlet was divided up into a number of estates and given to people such as Winna, to establish their farms. Catsley prospered to the extent that it was a separate manor by the time of the Domesday book; it seems places like Winwood took longer to grow from an isolated farm. Hence, by using place names, we can get insights into the very earliest stages of the growth of our local villages.

The Four Parishes Heritage Group are supported by the Local Heritage Initiative and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Nationwide Building Society.

Early quarries in Highley

It is not hard to find evidence of stone quarrying in Highley. Particularly by the river, a number of large quarries can still be seen and on the opposite bank the wharf for Hexton’s Quarry in Arley still has a load of unclaimed stone blocks which never made it down the river. However, these remains are from the end of the 18th century or later; quarrying in the village has a much longer history.