The Gothic Hall

One of the more mysterious buildings of the 20th century in Highley was the Gothic Hall. This stood on the site of what is now Highley Garage for twenty years from 1908. It was both a hall for meetings and entertainments and also the village’s first cinema. In spite of its importance, there are no certain photographs of the outside of the building; somewhat surprising considering the number of post-cards that exist of the High Street in Highley.

The Gothic was opened in May 1908. It was built by George Edward Bache, the landlord of the New Inn (and also the Ship). It was a typical early 20th century pre-fab: corrugated iron and timber. None-the-less, it was remembered as a very smart building. It had a particularly ornate façade, based very loosely on medieval, Gothic architecture, hence its name. For its first few years it existed as a hall for hire for concerts, public meetings, private parties and also for plays put on by travelling theatrical groups. Thus in early October 1908 Hybert’s Company put on “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, “White Slave” and “The Prodigal Son” before departing for Tenbury Wells, where presumably they repeated the programme. Previously an evening at the theatre would have involved a train trip to Kidderminster or Bridgnorth; the availability of the Gothic made this much easier.

In addition to plays, there were occasional film shows; moving pictures were rapidly gaining in popularity. In January 1913 the Bridgnorth Journal announced that an application was being made by Bache for a cinematographic licence for a new building in Highley. In fact the new building never materialised; the licence was granted for the Gothic Hall which was promptly sold to Ernest Copson. Copson renamed it the “Picture Palace” and began showing films. At first attendances were poor; it seems that the projection quality left a lot to be desired. There was also a small fire within a few weeks of opening. Eventually matters improved (although not before Copson parted company with his manager, Thomas Swift) and the Picture Palace (also sometimes called the “Electric Theatre” or by its former name of the Gothic Hall) became established. It seems to have provided picture shows several nights a week and been available as a meeting or concert venue at other times.

In 1915 it was taken over by Hector Lightfoot who ran it with his wife and son throughout the First World War. In 1921 the cinema licence was held by Mrs Jane Lloyd and indeed throughout the 1920’s the manager was her grandson, Sammy Richardson. However, shortly afterward, the hall temporarily closed. It was open again by 1925 when it was owned by Messrs Hill and Evans from Stourbridge and Kidderminster. Although films were still shown, its main business seems to have been hire by travelling entertainers and for concerts and dances. Richardson led the “Gothic Orchestra”. The end came in October 1928 when it burnt down. Around 1932 a new cinema, the Plaza, was built in its place.

The Working Men’s Club

(This was the site of Highley's first working men's club. Steward Arthur Jones stands in the door surrounded by members. Shortly before World War I, the club moved to new premises in the village.)

Working Men’s Clubs were established in many parts of the country towards the end of the 19th century. They aimed to provide the facilities of a public house but run for the benefit of the club members rather than for profit. The Highley club was registered on 7th November 1899 as the “New Castle Working Men’s Club”. Its offices were at the Castle Inn but it actually met in the New Castle Building; the first house on the left as you enter Highley from Chelmarsh and built that year. The exact relationship between the owners of the Castle Inn and New Castle Building and the founders of the club remains somewhat mysterious. The aims of the club were to gives its members “the means of social intercourse, mutual helpfulness, mental and moral improvement, and rational recreation”. Membership was by election, with the annual fee fixed at 1/- and the club was to be run by a committee of nine, at least two thirds of whom had to be bone-fide working men. The original applicants were Arthur Jones, Richard East, Ambrose Goff, Louis Turner, William Poundford, Isaac Beddoe, John Philpott, John Field, Noah Lawton and William Wedgbury, the secretary. Wedgbury was soon succeeded by Arthur Jones.

The club was known in its early years as “The Canteen”. At first it did not meet with everyone’s approval. Apart from the Ship, it was the only place in the village where wine and spirits were available; the other pubs could only sell beer. In 1901, when the New Inn applied for a spirits licence, one of the arguments advanced in its favour was that it would prevent the “excesses” of the club, which was not subject to the licensing laws. It was hoped that people would go to the New Inn instead of the club, forcing it to close. In 1908 the Bridgnorth Journal was forced to print an apology after quoting a Mr Yates of the Bridgnorth literary society, who spoke of 5 members at the club “turned out on the grass and during the night they got alright”. The club in fact had prohibitions against drunkenness, gambling or bad language and members were occasionally expelled. It joined with other village groups to support institutions such as Bridgnorth Hospital; a collection in 1902 raised £2-4-6½. Far from closing after the New Inn obtained its spirits licence, in 1904 it moved to a new club house in the village centre. Sister clubs were formed in Alveley and then Chelmarsh in 1907. In 1913 the club premises were extended by the construction of a new billiards room, reading and writing room, committee offices and cloak room. This extension cost £600 and the total premises were now valued at £2500; back in 1899, the starting balance was reckoned to be just £50. The club now had over 300 members. Soon a generator was installed so the club was one of the first buildings in Highley to have electricity.

Perhaps the ultimate signs of respectability were the dealings the club now had with the church and the “squire”. In 1913 the first joint Highley and Chelmarsh Club church parade was held and for several years this was an annual event. When the Rev. Shields was appointed as the new vicar of Highley, almost his first act on arriving was to join the club. John Oakley Beddard, the “squire”, spoke at the grand opening of the club extension in 1913 and after the war was frequently invited to judge the annual flower and vegetable show. New rules were issued in 1918; the document was almost twice the size as the 1899 rulebook, now with details of the finance subcommittee and other such minutiae; the club had property investments to look after. Some things had altered for the worst; membership was now 1/- per quarter; a 400% increase from 1899. The committee felt the need to introduce an extra rule, instructing that nobody was allowed in the billiard room in their “black or working clothes”, nor was smoking permitted over the table.

In a relatively short period, the Working Men’s club had transformed itself from “The Canteen”, a disreputable drinking den hidden on the very edge of the parish, into one of the village establishments. Unfortunately, many details of the early history of the club remain obscure but I am sure there is much more that could be written about it.

Memories of Woodhill Cricket Club

(Woodhill CC are at their new ground at Smoke Alley, Highley.

(Woodhill CC are at their new ground at Smoke Alley, Highley.

Top row (L to R) Bill Dudley (umpire from Chelmarsh), Ray Poyner, Frank Jones, George Poyner, Trebor Deeley, Reg Mullard, Tom Owen ("Owty"), Doug Westwood, Charlie Pritchard, Bill Warner

Bottom Row Bob Walker ("Tudor"), Trevor Bytheway, Dennis Oliver, Tom Westbury, George Davies, Norman Link)

[Article written by George Poyner, member of Woodhill CC]

I have recently bought a book about the history of Bridgnorth Cricket Club and it makes very interesting reading. It made me stop and think about Woodhill Cricket Club, the team I used to play for in my younger days. I think it started about 1927, when they used to play on Woodhill Farm in Highley, hence the name. As a child before the war, I used to go down to the field to watch them play. They had a nice wooden pavilion and it was very nice sitting out in the country. The players usually gave us children the “left-overs” from their tea; that was probably the main attraction in those days. A slice of cake or a sandwich was always welcome! One of the old teams dismissed Arley for 4 runs! The team folded in the war.

We started up again about 1948. We had no ground or pavilion and so we could only play away matches. Then we managed to get a piece of ground down by Smoke Alley and the fun started. We had to dig the ground with spades, roll it and seed it to make a good wicket. Then we had to fence it with steel posts and barbed wire to keep the animals out. We had a wooden shed at first to house our push-mower in, then when we had managed to get some funds, I built a new pavilion, with a little help from the other players. After about 2 or 3 years the farmer wanted the ground back and so we had to find another place. Our next stop was Netherton Farm, where the golf course now is. Of course, the pavilion had to be dismantled and moved, causing a lot of damage as it was asbestos. We struggled on and put it all together again and made another cricket pitch fit to play on, for another 2 years. Then the farmer moved us on again to a field on the other side of the road but we left the pavilion where it was and put a gate in the corner of the field so we could get through to it. All went well for about another 2 years, then the new landlord at the Malt Shovel started to play for us. He decided that we would be better off by playing on one of his fields! So once again the pavilion had to be moved and another pitch prepared. We purchased turf for it this time and had a bulldozer in to level the field. We had our teas at the pub and of course the players would go there for a drink afterwards, so it was extra trade for the landlord. The only trouble was that he was not a very good cricketer but we had to pick him to stay in his good books! We stayed here until the team folded through the players getting older; some were in their late 60’s.

We used to have some good games playing all the local teams. Most of the villages had teams in those days and we also played sides from Birmingham and Wolverhampton. We often had 3 or 4 players from one family; I played with my brothers Ray, Des (Slogger) and Geoff. The photo shows the team in about 1950. We used to play in the Bridgnorth Knock-out and the Highley Knock-out, holding our own against most of the country teams. We made some good friends and had many enjoyable matches.

Miss Newey’s School

(Miss Newey ran a private school at the Stone House in Highley. This photograph is from the early 1930’s. (L to R, back row first); Miss Newey, Rene Lloyd, Eva Breakwell, Audrey Brick, Ethel Perry, Doris Robinson, Agnes Elcock; (middle row) Johnny Huntly, Doreen Bache, Muriel Binless, Marion Pearce, Thelma Swift, Backhouse Binless; (front row) Leslie Bache, Raymond Holford, Neville Brick, Ken Holford, Dennis Bache, Ronnie Davies.)

(Miss Newey ran a private school at the Stone House in Highley. This photograph is from the early 1930’s. (L to R, back row first); Miss Newey, Rene Lloyd, Eva Breakwell, Audrey Brick, Ethel Perry, Doris Robinson, Agnes Elcock; (middle row) Johnny Huntly, Doreen Bache, Muriel Binless, Marion Pearce, Thelma Swift, Backhouse Binless; (front row) Leslie Bache, Raymond Holford, Neville Brick, Ken Holford, Dennis Bache, Ronnie Davies.)

Mention “private schools” to most people and it will conjure up visions of places such as Harrow or Eton, or “prep” schools. I suspect many would be surprised to learn that between the wars, Highley boasted a private school that educated a number of well-known villagers.

A Miss Caroline Newey appears to have arrived in Highley at the end of the First World War. Initially she rented “Waroona”, the large house on the bank between Clee View and Garden Village and usually the home of the various village doctors. I do not know where she came from or why she moved to Highley, but she started a school, presumably at Waroona. In the early 1920’s she moved to the Stonehouse, just up the lane behind Waroona. This had originally been a farm, but its land had been sold when Garden Village was built. She now ran the school from the house. Most of her pupils came from Garden Village; the County school was at the other end of Highley and a long walk away (as I can testify from personal experience!). Garden Village mainly housed miners, but the area had its own shops, pubs and of course was surrounded by the much older farms. Quite a few of her pupils seem to have been sons or daughters of the local tradesmen or farmers, although some mining families also sent their children there.

Miss Newey obviously made a reasonable living, for her school was still flourishing in the early 1930’s. I am very grateful to Mrs Marion Breakwell (née Pearce) for lending me the photo above, showing the school in about 1930. The children are of all ages; I assume Agnes Elcock worked for Miss Newey as a helper. Shortly after this picture was taken, my father, George Poyner, started at the school; living in Garden Village it was much easier for him to get to than down the village. After he had been at the school about a year it closed; judging by the appearance of Miss Newey in the photo, I imagine she had decided to retire. This must have been in about 1933. All George can recall is playing with a train set in the class room; in fairness, that is pretty well all I can remember of my first year at Highley school over 30 years later!

The New Road

(The New Road was built from 1927-30,

(The New Road was built from 1927-30,

largely by hand)

The “New” Road is today the main road south from Highley. However, as its name suggests, it is a comparatively recent addition to the local road network, dating from 1930.

Before the New Road was built, there was simply a track heading south past the churchyard, eventually meandering out into some fields near the river. The main road to Bewdley and Cleobury was via Borle Mill. This must have posed quite a challenge to horse and carts and was frequently quite beyond the capabilities of the early motorised vehicles. It was a common occurrence for cars, lorries and buses to get stuck on the bank. Some incidents were more dramatic; in 1919 the steam roller belonging to Cleobury Mortimer District Council (who were responsible for Highley) ran away down the bank and collided with the bridge, doing considerable damage in the process. It is likely that losses to the municipal pocket weighed more heavily with local councillors than the misfortunes of the private motorist; in 1925 the District Council applied to the Ministry of Transport for a grant to construct a new road out of the village on easier gradients. The cost was estimated at £27,500 and the Ministry would pay 75% of this. Whilst the council doubtless calculated that the road was needed purely on grounds of transport, they must also have been aware that it would also create new jobs in the village. I suspect that the scheme was soon taken over by the County Council. Plans were drawn up at one stage for a second road leading to a bridge over the River Severn, but these were soon abandoned leaving just the link out of Highley.

Work seems to have started in 1927, under the supervision of Mr Bradley. Stone was obtained from quarries near Kinlet on the line of the road and also apparently by reopening a riverside quarry at Stanley. This was brought close to the site of construction either by lorry or horse and cart. The Highley Mining Company’s railway leading to the old Billingsley Colliery was also used for transport as it crossed the site of the road in Kinlet. At the point of working there was a temporary narrow gauge railway, used to bring stone to the site or move spoil away. The harder rock was removed by blasting but much work was carried out by hand. Once the embankments and cuttings had been formed, the road surface was made with a steam roller. There were two substantial bridges, one over the Borle Brook and then almost immediately afterwards a second over the colliery railway.

The Highley men employed on the project continued to live locally. However, there was a living van parked at Kinlet; presumably specialist workmen such as the steam roller driver lived here during the course of the week. Local hauliers benefited especially from the work. The New Road was particularly important in helping the Whittle business; a lorry was used for haulage for most of the time but was swept out, covered with a tarpaulin and then driven by the late Frank Jones to take Clee Hill miners home from Kinlet and Highley pits. This was the start of Go Whittle coaches!

The bridge over the Borle Brook was underway in May 1930, in spite of delays over the spring due to heavy rain. At the end of September 1930 it was announced that the road would be open the next month. As far as I know, this did indeed happen, with very little ceremony.

The wheelwright

(John Derricutt in his workshop about 1950.)

(John Derricutt in his workshop about 1950.)

Of all the country craftsmen, it is perhaps the wheelwright who is best associated with a vision of vanished rural England. There is something particularly evocative and timeless about this rural woodworker, making and maintaining the farm carts and wagons that kept the countryside moving in former times.

The craft of the wheelwright is certainly both ancient and important; by the end of the Middle Ages he had evolved from the general carpenter with his special skill in making wheels and from then until after the First World War almost every village would have a wheelwright, often working closely with the blacksmith.

I have recently been fortunate enough to look over a series of ledgers kept by one local wheelwright, John Derricutt. John was born around 1869 and his father was an important farmer, related by marriage to the Jordan family, the “squires” of Highley. John did not follow his father into farming but instead became apprenticed to a wheelwright, setting up in business in Billingsley in 1889 at the Bind Farm, which his father then worked. Within a few years, John had moved to Highley, to Borle Mill. There he combined the roles of miller with wheelwright. John Harley was the long-established wheelwright in the village, living at Rose Cottage in the village centre. However, following Harley’s death in 1909, John seems to have bought the business and moved to Rose Cottage, where he remained until his death in the 1950’s, latterly working in partnership with his son, Leslie.

The ledgers show the work that John undertook. It covered a wide variety. Initially he concentrated on the traditional business of making and repairing carts and wagons. A brand new cart before the First World War would cost around £10. A flat-bedded wagon would cost twice this. Whilst he might get a couple of orders a year for new vehicles, most of his wheelwrighting involved repair of existing ones. Wheels needed regular maintenance: new tyres, spokes or rims (felloes). The sides of the carts were built up with struts and planks (rathes and the cratch) so they could carry extra loads and these frequently needed replacing. He also maintained the floats of the village tradesmen and the traps that were the equivalent of the family saloons.

Most wheelwrights also undertook general carpentry and John was no exception. He was fortunate to be in business when the village was turning itself into a small town. Whilst he did not build houses, he was kept busy with a host of repair and maintenance jobs, both for householders and shopkeepers. In 1909 he had a particularly large job, rebuilding a barn for the village squire. Soon after that, the Billingsley Colliery Company began building a new colliery, railway and houses, and he found regular work cutting timber for the company’s main contractors or repairing their plant. He did not restrict himself to carpentry, also doing plumbing, glazing and mechanical repairs. Like many country carpenters, he was also an undertaker.

Whilst John was in some ways the typical traditional wheelwright, his accounts show how he adapted to changing times. As an apprentice, he would have had to make everything he sold; working in Highley before the First World War he found it much more cost-effective to purchase items such as wheel hubs or spokes from specialist merchants in Kidderminster, Bridgnorth or Shrewsbury. These would arrive within a day on the train. He was shrewd enough to turn his business from a wheelwrights in the 1900’s to that of a general builder in the 1950’s. He readily adopted powered woodworking machinery. His business in the 1950’s was very different from the one he started in 1889.

The Fire Brigade

It was (and to some extent still is) a common complaint amongst Highley folk of a certain generation that as the village has got larger, its facilities have got smaller. There is certainly some truth in this; fifty years ago Highley had a much wider range of shops, a cinema, two full time policemen and so on. For a relatively short period it even had its own fire brigade.

The fire brigade was set up in Highley as a war-time, emergency measure. It was part of the Auxiliary Fire Service, which was introduced to provide voluntary back-up to the professional firemen. In 1940, Highley had a total of 6 stirrup (hand-worked) pumps to cover the whole of the village, a state of affairs the parish council found alarming. By August of that year a trailer pump had been provided by the District Council and Mr Stonehouse, the colliery manager, was asked to help train a crew to work it. Eventually the Highley brigade two fire engines; a pump engine and a tender of 10,000 gallons capacity. The latter was important as the water supplies in Highley were erratic. In 1942 the Fire Service announced it was to build a large 5000 gallon tank in the village (although I am not sure this ever happened!). In 1944, dealing with a small fire apparently depleted the village’s drinking water for 3 days.

Some years ago the late Jim Mantle gave me an account of the fire brigade. There were 22 men, under the command of Lewis Jones, although Jim and Jack Evans also had the rank of leading firemen. The fire station was on the site of the present day Assembly Close. The brigade were usually controlled from the full-time station at Bridgnorth. The crew would be summonsed by an alarm on houses next to the Working Men's Club; when it went they would immediately make their way to the station. The first man who arrived would answer the telephone to find out the nature of the emergency and open the garage doors to allow the engines out. Together with the leading firemen, Josh and Tom Tolley formed the skeleton crew, always on call. Others came when available.

The crew had a variety of duties. Fortunately they were rarely required for action in Highley. Frequently they were called out to provide cover for the Bridgnorth crew who had been called to a large fire somewhere else in the district. They ventured as far as Claverley to deal with fires. One of the most dramatic incidents they attended was when a house was bombed in St Leonard's Street in Bridgnorth. Five lengths of hoses had to be run out from the river to St Leonard's Street for water. The site of the former house is now a Garden of Remembrance.

Apart from real fires, the crew were also called out for practice drills. There were also competitions. The Highley Brigade once beat the regulars to win a cup for target practice. This involved hitting a target with a jet of water five hose lengths away.

With the end of the war, the AFS was stood down and Highley once again relied on the neighbouring towns for fire coverage. There was a proposal for the old station to be used as a garage for an ambulance but it was eventually taken over by the Pen Factory, newly arrived in the village. When the Pen Factory moved to their present site the building was demolished. Now there are only a few photos of the brigade left and some memories.

Highley Band

One of the pleasures of Highley is the presence of the Band at many village fetes and events. The band was formed about a number of years ago, largely through the efforts of Ray Millichamp. However, many older residents will remember the original band, founded at the turn of the century and which lasted until about 1960.

The events surrounding the start of the band are a little mysterious. The band itself dated its origins to 1897. However, the Bridgnorth Journal records a Highley Brass Band playing at village fetes in from 1893-4. This may have been associated with the “Oddfellows”, a National Friendly Society with an active branch in Highley at this time. Presumably this band soon folded. In 1897 the leading figures in the (re?)formed band were James Frederick Lloyd, owner of the local village stores on the corner of Silverdale Terrace and James Booth Jones, a deputy at Highley Colliery and a near neighbour of Lloyd’s. Early practices were held in Lloyd’s bakehouse. The first uniforms were purchased in 1903 for £22. A photo, probably of this date, shows the bandsmen posing proudly in their uniforms with J. F. Lloyd holding the conductor’s baton. The band played regularly at village fetes and events. In 1903 they gave a series of free concerts to raise money for a new pulpit in Highley Church for a memorial for the late Private Tom Davies, who died in the Boer War. In 1913 the band and the local cricket team formed a joint committee to hold a village sports day; the forerunner of Highley Carnival. This arrangement existed for many years.

The years before the First World War were in many ways the high-point for the band. In the 1930’s the late Jim East, the band secretary, recalled those days in an interview for the “Highley News”, a local newspaper. They frequently played at local shows, travelling by horse and trap and could be away from home for 16 hours at a stretch. The Highley Mining Company was generous in granting leave to bandsmen. On the day the First World War was declared the band was playing at Kinlet Hall and witnessed the sudden departure of Colonel Childe to join his regiment. In 1914 the band was preparing for contests but war prevented this. He contrasted those times with the present, when he claimed it was difficult to recruit members. (Nostalgia is not a new emotion!).

It probably was the case that in the 1930’s the band was finding it harder to recruit members than before the First World War. Certainly in the Second World War it suspended activities although it restarted afterwards. A new generation of villagers joined up; perusal of a photograph of the band taken probably in the 1950s outside Chelmarsh Working Men’s club shows a number of fresh-faced youngsters who today look rather more the worse for wear! Easy transport out of Highley to the bright lights of Bridgnorth and Kidderminster plus the lure of the TV probably killed the band off in the 1960s.

There are numerous anecdotes concerning the old band. To relate just one, it is said that during a Christmas Carol concert, the conductor announced that the next carol would be “While Shepherds Watched”. A certain bandsman turned to his neighbour and muttered “I’ve just **** played that”.

Mike Wall of Braginslye Farm in Chorley, is compiling a history of Highley band and I am sure he would be pleased to hear of any information about it.

The Polly

The Polly was an old barn where dances were held most Saturday nights. It was situated at the back of the Malt Shovel pub in Green Hall Lane and belonged to the then publican, Sam Brick.

It would be in the twenties. The Barn was two-storied with the Dance Hall on the ground level, while underneath pigs were kept. Dances were mostly the Lancers, Waltzes and all the old timers of that period. The Band consisted of old Joe Wilson on the concertina and George ‘Buffer’ Jones on the violin. After a couple of hours drinking good ale at the Malt the dance got going like a bomb. Most of the men were farm labourers or miners, the farm-hands being easily identified by the posh leggings they wore in those days. The ladies wore their Sunday best frocks. Sometimes Old Joe would doze off a bit and then the sounds were unbelievable but all in all, everyone enjoyed themselves. Sam Brick was all for the dances for then his beer trade was good, very good. There was of course the occasional ‘punch-up’, mostly over a girl I suppose, but it was soon sorted out and then back to the floor.

The Hall was lit by oil lamps placed every half dozen yards and garlands were hung up to make it look professional. Towards midnight, the noise of the dancers, the singing and sweating was tremendous. The cost to go in was 6d but even that was too much for some lads for 6d was 6d in those days. Some managed to get in free and that was something, for there were only two doors and one of those was kept locked. There was not much vandalism in those days but the youths were all for a bit of fun and very quick to size up the right time for it. The Polly was quite a good length but low with small windows. A small passage way led to the admission door and at the end were sacks of ground wheat for the pigs. The youths who could not get in because of financial troubles saw the chance of some fun one dance night. Quickly they dragged the bags to the entrance door and placed one on top of another with the ends opened. All this had to be done very quickly in case someone came out of the dance. They then dashed out into the Green Hall Lane and waited for things to happen. And they did.

The weight of the sacks made the door hard to open and it must have taken two or three men to do so. Then, crash – the bags fell into the Polly. White dust quickly spread through the hall and could be seen seeping through the little windows. The dancing came to an abrupt stop and the coughing, spitting and swearing was music to the youths’ ears. They were concealed by now, in the field, ready for a quick getaway. Then the dancers came staggering out, scrambling humans as white as snow. The dust settled rapidly and Joe and Buffer got their instruments going for the dance to continue, for nothing could stop the Saturday Night Hop. Many enquiries were made to find out ‘Who done it’ and it would have been Lord help the youths if ever they had been found out.

Later on the boar that was kept with the pigs underneath the dance hall died. It may have been from natural causes or perhaps from the noise of the dance but, whatever it was, the Polly came to an end. The ruins of the hall are still there [The Malt has recently built a new, stone building on the site, DRP]. It brought a lot of pleasure to the locals in the days when there was nothing in the village. Above the ruins are two large sand rocks made into steps. These were used for horsemen using the pub to mount or dismount easily. They are still there and may well be the only ones left in the village.

With thanks to George Pike

John Oakley Beddard

We are again indebted to George Pyke for allowing us to publish another of his reminiscences of his life in Highley. This time it is his memories of John Oakley Beddard (1867-1944), who, for most of the first half of this century, filled the role of “squire”, owning most of the south of the village. Beddard inherited the Netherton Estate from his father in 1900 and, by the standards of Highley, lived in some style. He is buried next to his father and the long-serving vicar, Rev. Shields at the entrance to the churchyard.

David Poyner

John Oakley Beddard was the Squire of Highley for a good many years. He was the owner of the big Netherton estate which extended into Kinlet and a magistrate on the bench. A very wealthy man, his vast fortune came from the royalties off coal mined by the two collieries, Kinlet and Highley. He received sixpence a ton from all coal mined on his estates. The family home was a mansion type house on the Netherton road at the top of Borle Mill (i.e. Netherton House: DRP). Opposite was the coach house and both places are now lived in by other people, the whole lot was sold up in sections after his death.

Beautiful trees, shrubs, flowerbeds and lawns were kept in immaculate taste by the gardeners who were employed. I well remember the pony and trap that he and his family used for transport. The waterfall on his land, just above the old Mill House, was the most picturesque and beautiful place in the area. (This collapsed in the floods of 1947, but its site is still visible; DRP) Great fir trees shaded the ground in summer and kept the shrubs good in winter. The family would spend many hours there in the warm weather reading, drawing and painting. Can you imagine the lazy brook running along, twisting and winding its way to the Severn, then suddenly cascading over the falls into deep water below some ten feet below? The falls served many purposes, keeping the water deep for the trout that abounded there, turning the water for the Mill below and lastly stopping the coarse fish from the river upstream. A thousand pities that this has all gone.

When the Squire visited the working Men’s Club, word would go around the grapevine, and miners would flock there, for it was always a drunken orgy and nearly all the locals got tipsy on the free beer and whisky, etc. It used to be a “long sitting” and at the end of it the Squire would be unable to even stand. Then there would be a lot of scheming to see who took him home in the trap and get the money reward he always gave.

When things went a bit wrong, he would rave and rant at anyone near him. His normally red face would go purple until his wife or Pat Evans, the servant, talked him down. After his death, the whole estate was sold up and the family moved to other parts.

Horace Cooper

When I first got to know Horace he was a Sunday School teacher in the church hall by the school that has now closed. Believe it or not, I was one of his pupils and we had a great time with him because there was nothing too big or too small for him to do for us.

For many years he was the shaftsman at Highley Colliery, working only the night shift but, by his very persistence, he became the First Aid man when Bill Bevan left. First Aid now became his life. He had his own office and rarely went underground except to accidents.

When Horace made up his mind about a certain thing, nothing in the world would change him. He was a very well-known football referee, well- known only because of the amazing decisions he made on the field of play. Like the time when he was refereeing a local derby between Hampton Loade and Chelmarsh in the old Bridgnorth League. Both teams comprised mostly of miners who worked at Highley, Kinlet or Billingsley Collieries. Hampton Loade were winning handsomely when Horace abandoned the match a half minute from time because of the very bad conditions. Need I say there was a war on and Horace was lucky he was not lynched. His ten-page report went in his favour and the match had to be replayed.

There were very few organisations that Horace had not been on sometime or other. When the Highley Colliery was transferred to Alveley, he had a First Aid place there and so keen was he on his job that I think he would have tackled an operation. When the Baths were built, Horace became the Superintendent, as he liked to be called and walked around with a white coat on. At around this time he became interested in photography and joined the Bridgnorth Camera Club where he soon learnt to develop his own prints. In a competition for a ‘Still Life’ he put a print in of a tombstone in Highley church yard and argued that he was right. He had the courage of his own convictions and although he was a very stubborn fellow he had a big heart and would help anyone he could. Sunday School teacher, referee, first aider, councillor, pie hander-out and a host of other things made up the life of Horace Cooper.

George Pyke

George’s recent article on John Oakley Beddard, the ‘squire’, has provoked some interest. A number of readers of the ‘Forum’ have their own recollections of Beddard. One remembered how Beddard found his grandmother a cottage when she had to move off the Kinlet estate; as the largest landowner in Highley and also a JP, he was not afraid to use his influence to help local people. The story is also told of the occasion he picked up a group of miners straight from the pit and took them down to his favourite establishment in Worcester. However, as the miners were still in their working clothes, the landlord at first refused to serve them. However, his attitude soon changed once Beddard pointed out that the men were his guests and his continued patronage of the establishment would be at risk if they were not served promptly. Apparently there was marvellous change in the attitude of the landlord at that point…

David Poyner

Memories of Dick Walford and Jack Whitney

Dick Walford

Most of the old Highley characters had a nick-name. Dick was known as “Truant”, probably because no one could hold him in school. When I first got to know him he lived at 10, Clee View with his father and a few of his family. The 1914-18 War came and Dick had to go. Very early on he was captured by the Germans after a battle in France, then sent to Germany to work in the coal mines. It was because he had worked in the pits that he was sent there, but he never would work and only did what he was forced to do. A fellow prisoner said Dick was a true Britisher and would not help the German cause.

Armistice came and Dick came home, only to find that most of the family had gone, leaving only the “old man” and himself to carry on. They got behind with their rent to the Highley Mining Company who owned the houses now, and were moved out for the families which worked in the pits. So, having nowhere to go, the two took to the woods where they built a bit of a shack by the old railway just above the first bridge going up to Friars Moor. They depended on relations living in Clee View for some food, but I know they lived well on rabbits and pheasants which were abundant at the time. Dick was a first class poacher.

Having survived two very bad winters, they had to pack up when the old man became ill and was taken to the Workhouse in Bridgnorth. Dick was picked up by the Police and sent to gaol for vagrancy. The father died and when Dick was released he was on his own. Little Kate Smith took him in and, for the first time in a good number of years, he was contented. He did different jobs around the village, then went back into the pit. His one great love was his pigeons.

Little Kate died, so once again Dick was on the move. Then luck changed when the family was left money by a sister who had married well. Unfortunately Dick developed T.B. and had to live in a hut by the side of his brother Tex’s house. The money soon went and so the struggle for existence started again. Then the unexpected happened. He fell down and broke his leg. Nearing the 70’s and in poor health, he never recovered. The rough, tough life he had had took its toll, but he never complained. He took what came to him in the way old soldiers of the 1914-1918 war did.

Jack Whitney (Skit)

Skit lived with his family at 9, Clee View after having been moved from the cottages at New England when they were demolished. He was a miner at Billingsley and Kinlet Collieries. Eventually he was left with his dog that was his constant companion. He never seemed to have much purpose in life except to work now and again to get money for drink and smokes.

Skit was a regular Malt Shovel man having his own particular place by the great open fire grate, smoking twist and drinking “Ansells”. The old pub has been altered very much over the last few years, so much so that if the old timers could come back they would never believe it was the Malt.

Skit, like Dick Walford, was a real poacher and his faithful dog could always be relied on to get a rabbit for the pot. Rabbits, in those days, were as numerous as flies. With the spreading of myxomatosis they seemed to vanish over-night and have never come back as before. Skit was a very rough man but did not interfere with other people but would fight like a madman when drunk. The very familiar sight of him and his dog was lost to the village when he died.

George Pyke

Old receipts

Most of us have drawers stuffed full of “important” paperwork; bills, receipts, letters and so forth; periodically this gets sorted and discarded. Inevitably, the odd item gets overlooked and so lingers for years after it should have been thrown away. Of course, most of these bits of paper are usually of little or no interest, at least to the owner. However, if they have survived long enough, then they can become of historic interest.

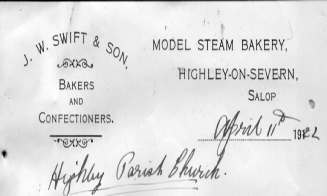

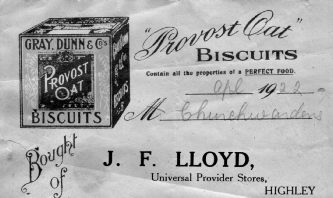

I have recently been shown an envelope of old receipts and letters. They date from 1921/2 and belonged to William Parton, one of the churchwardens of Highley; they were kept together to allow him to prepare the church accounts at the parish AGM and never thrown away. Needless to say, 86 years later, they make interesting reading.

1921/22 was not a financial success. Expenditure, at £111-11-5, exceeded income by £3-5-3; indeed, a report of the AGM notes that it was hoped that the congregation would increase their giving next year. Some things never change... The offerings from the congregation were the sole source of income; the days of church fetes and jumble sales were yet to come. The largest single item of expenditure was the payment to the organist, Reg Parton, of £18, followed by the £16-5-0 paid to the church clerk, William Robinson. Equally, the Easter collection, traditionally retained by the vicar, the Rev Shields, came to the not insubstantial sum of £8. However, the church gave away almost £14 in donations, including just over £5 split between Kidderminster and Bridgnorth hospitals; in 1921 there was no National Health Service.

The balance sheet, whilst informative, is by itself rather dry. What particularly adds colour (sometimes literally) to this collection of documents are the bills from the various suppliers to the church. H. Stoddart of London supplied six bottles of Sacratina “the perfect sacramental wine” for Holy Communion. This was despatched via the railway and marked “very urgent”; one wonders if someone had miscounted the bottles in stock in the vestry! The bier, currently on display outside the church, was new in 1921 from Messrs Archer and Son and cost £40. The hut in which it was housed was also new that year and came to £45, being constructed by J.P. Ellams, a Highley builder. However, for general maintenance about the church, John Derricutt, the local wheelwright, was used. His work included repair of lamps in the church and new ropes on the chiming apparatus that was used to ring the bells. General provisions came from J.F. Lloyd, “Universal Provider”. Lloyd’s store was the first to open in Highley and stood on the corner of Silverdale Terrace where the new houses have just been built; he had regular orders for items such as floor cloths, Brasso, glasses for lamps and brooms. Another regular supplier was J.W. Swift “Model Steam Bakery”. Swift’s was opposite Lloyd’s; it is now a grocery. Somewhat surprisingly, Swift supplied not bread but coke, to heat the church. This was presumably resale of fuel for the baking ovens. The Highley Mining Company was a more expected supplier of coal, also for heating. Why coke and coal were both needed is not clear.

The billheads themselves are interesting items; some examples are shown below. I would like to thank Mr and Mrs Warrington and Eric Edwards for this fascinating collection; if anyone else comes across similar documents stuffed in an old envelope, please let me know!

This work was carried out by the Four Parishes Heritage Group on a project supported by the Local Heritage Initiative and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Nationwide Building Society.

Football in Highley

For the first time in over a century, Highley does not have a village football team. Many, myself, included, were sad to hear about this; however, whatever the future might be for organised football in Highley, there is no denying that it has had an illustrious history in the village. There are probably people better able than myself to write about the history of the village football side and the numerous trophies it has won over the years. This article takes a sideways look at the history of football, by considering how many professional footballers have played in Highley, either in their early days playing for Highley itself, or as members of visiting teams. Not everyone here was a full-time professional and some never made the first team, but all could make some claim to have been on the books of a professional side.

Although I understand that the FA officially considered that the Highley side began life in 1897, the earliest records I have seen of football teams in the village are just a few years later when teams formed around the church and the chapel; Highley St Mary’s and Highley Primitives. Occasionally there are mentions of Highley Unity, perhaps when the different teams came together. Highley Colliers, the direct ancestor of the village side was certainly in existence by the First World War and it was this team that established the village’s reputation by winning the Shropshire Junior Cup in the 1914/15 season. Professional football was of course well established by this time and from this distant era, two Highley men made the big time. The first was said to be Howard Shivelock, although I know very little about him. However, the second, Jack Hartland, was a stalwart in the Highley Colliers sides in the years either side of the Great War and was part of the team that won the Shropshire Junior Cup. He played for Walsall for a period.

Highley Colliers became Highley Miners Welfare in 1930 with the opening of the Welfare Ground and in this latter guise they continued to have great success well into the 1960s. Billy Brookes once scored 60 goals in a single inter-war season for them, and he followed Jack Hartland’s trail to Walsall. After the Second World War there was a comparative flood of Highley men to professional clubs, at least for trials. The most successful of these was Gerry Hitchen at Aston Villa who, of course, also played for England and was also one of the first English players to move successfully to an Italian club. Stan Jones played for West Bromwich whilst Aubrey Haycox (Villa), Stan Gwilt (Derby) and Bill Price (Wolves) were also associated with professional clubs for a while. More recently, Ted Hemsley enjoyed a distinguished career with Shrewsbury and Sheffield Utd.

Highley also saw numerous individuals playing for other sides who were to become, or who had been, professional footballers. Geoff Billingsley, an Alveley goalkeeper, played for Villa. Many men played in Highley as a result of cup competitions, particularly the Highley Nursing Cup. This competition was run in the 1930s and 40s to raise funds to support a district nurse in Highley. Particularly in the Second World War, it attracted teams from the army and the air force. The RAOC and the RAF sent teams but the most prominent successful were the 20th ITC, the Infantry Training Corps. The ITC included numerous physical training instructors and a number of these had been professional footballers before the war; indeed most resumed this career afterwards. The most famous was undoubtedly Billy Wright of Wolves and England, a man who for many years held the record for England caps. Johnny Hancocks was another with an England and Wolves pedigree. Others included Percy Lovett (Everton), Keith Jones (Villa), Ray Brown (Stoke), W.G. Richardson (West Brom) George Little (Doncaster), Amos (Birmingham City) and Cunliffe (Sheffield Wednesday).

From time to time, local professional clubs would send sides to play in friendlies at Highley, usually for charitable events; I have made no attempt to include them in this list. What is here, based on memories, is certainly incomplete and may well contain errors; further information welcome!

More football in Highley

Last month I took a look at some of the professional footballers who had played in Highley, for the village itself or in visiting teams. This in turn inspired me to look more deeply at the origins of the game in Highley.

Modern football took shape in the second half of the 19th century. Locally, it became established in Kidderminster by the start of the 1880s; I suspect it was also being played in Bridgnorth around this time. However, it took a long time to find its way to Highley, in spite of the rapid growth of the village because of mining. Although a cricket team became part of village life in the early 1880s, there is no record of football being played until the late 1890s. The FA officially considered that the Highley side began life in 1897; the first report in the Bridgnorth Journal is from the end of the 1897/8 season when “Highley Drivers” lost somewhat embarrassingly to Alveley Juniors 6-0 in March 1898. Highley Drivers sound as though they were made up from the pony drivers who worked down the pit. These were youths who looked after the pit ponies and this would explain why they were playing against a junior (i.e. youth) side from Alveley. It would be surprising if none of the older men at the colliery were also playing football, so it seems likely that there would have been some kind of senior side in the village as well.

In February 1900 a first concert was held for “Highley Unity”, apparently a new football team. If the name is anything to go by, it would suggest that the club was formed by the amalgamation of at least two existing teams, perhaps the drivers and their more senior colleagues. There are records of them playing a number of fixtures in 1901. Then, there is no more about football until a rather mysterious account in March 1904 of a game between “Highley” and “Highley Albion”, won 2-1 by the latter. It looks as though Highley was not as united as its supporters would have liked.

In 1906 the first reference appears to Highley St Mary’s and from now the story of football in the village becomes clearer. The name shows that this side must have been associated with the church; many football teams were founded by churches or chapels as the team ethos was thought to promote desirable virtues. St Mary’s quickly picked up support throughout the village and they were the first Highley side to make their mark in the wider world. In March 1907, over 200 people from Highley saw them narrowly lose in the final of the Worcester Charity Cup to Worcester St Clements. Two years later they returned to the final and this time claimed the trophy, beating Berwick Villa 3-1. By this time they were playing in the first Division of the Kidderminster League. In spite of their links with the church, they seem to have had a no-nonsense style of play; in October 1909 the entire team was ordered off the field after an incident in a match with Broseley.

Highley St Mary’s disbanded at the end of the 1909/10 season. By this time there were two other teams in Highley, also in the Kidderminster League, Highley Vic’s and Highley Swifts. The latter may have been the reserve side for the Vic’s. Perhaps bolstered by former St Mary’s players, the Vic’s took their place as the premier village side. However, they seem to have foundered at the end of the 1911/12 season. The other teams in Highley were now the Adult Class, another church-based team and the Primitives, from the chapel. Like the old St Mary’s side, the Primitives followed a particular form of muscular Christianity; a Kidderminster Infirmary cup tie was abandoned in March 1913 after a Primitive player refused to leave the field after being sent off. The Adult Class inherited the mantle of St Mary’s and the Vic’s in being the premier side but they and the Primitives both withdrew from the Kidderminster League at the end of the 1912/13 season.

In September 1913, an application by a new club, Highley Colliers, to play in Infirmary Cup was refused; there was no Highley side in the Kidderminster League. The Colliers had more success in entering other cup competitions. Following a 3-2 defeat of Droitwich, the Kidderminster Chronicle was forced to concede “that their exclusion from the local league was a mistake” and they were admitted to the league for the 1914/15 season. In the event, the First World War curtailed that season. Fortunately, it did not stop the Shropshire Junior Cup, which the Colliers won, confirming Highley as the best village club in the county. Highley continued to be dominant in local football for another 50 or so years.

Cricket in Highley

Over the last two months, I have taken a look at the history of football in Highley. This month I want to look at early history of the summer game, cricket.

Nationally, as an organised sport, cricket predates football and so it is not surprising to find that this is the case in Highley. It may also not come as a total surprise to learn that the first reference to cricket in the village is actually to a game that was rained off. September 24th 1864 saw the opening of Highley School. The Bridgnorth Journal reported that rain prevented cricket, rounders and croquet, so there was dancing in the school instead.

It would be surprising if cricket was not played informally in subsequent years in the village, but there was no organised club. It took the arrival of the colliery before a village team was formed. A diary kept by Noah Lawton, a winding engineman at Highley Colliery, records for the 14th April 1883 “Cricket club started at Highley”. The club was called Highley Rangers and seems to have drawn heavily on the newly-arrived miners. Cricket was well established both in Bridgnorth and many of the surrounding villages, probably encouraged by either the local gentry or clergy and so there was no shortage of teams who could give Highley a game. Their first match was on Whit Monday (14th May) against Chorley. Chorley may have been the established side, but they found Highley far too strong. They were bowled out for 17 in their first innings. In response, Highley made 57. In their second innings, Chorley fared even worse, being dismissed for just 13, leaving Highley the winners by an innings and 27 runs.

Although the next mention that I have of the club is not until 1888, it seems that their first victory was no flash in the pan. It was reported that in the 1887 season, they won 12 out of 14 fixtures. It is likely that these were all friendlies and the majority would probably have been single innings games. One key to the village’s success was JF Lloyd, the local grocer. Research by Malcolm Lloyd has shown that Lloyd was one of the outstanding local cricketers of his day; in the 1860s he was known as the “Bridgnorth Colt”. His move to Highley in the 1880s to open his shop was highly fortunate for the cricket team. It appears he had lost none of his skill of his youth; he opened the batting for Highley and frequently was the top scorer. He was also no mean bowler. The club was not particularly optimistic about the 1888 season, as over the winter a strike at the pit meant that a number of players had left the village; in the event, they were still strong enough to beat Bridgnorth Seconds by 41 runs in a game in June of that year.

In 1898 a concert and dance held in the schoolroom for the club raised £8. It was reported that “in recent years, members have made the ground and the pavilion and now an outfit was wanted”. The cricket field was, as far as I know, on the site of the present Rec. In May that year, they were involved in a dead heat with Bridgnorth, both making 42.

By the early 1900s, the club was known as Highley Colliery Cricket Club. Herbert Stonehouse, one of the directors of the company, was a particularly keen cricketer. However, the club was open to anyone in the village. By now it was playing in the Kidderminster League, against teams such as Cookley or Stourport. Arguably this was the period when it enjoyed its greatest success. Jim Brick led the batting and in 1914 scored the first century in the league. JP Ellams was also a fine batsman, having at one time represented Staffordshire. Tom Duffill and Tom Westbury spearheaded the bowling; in 1910 Duffill took half the team’s wickets at an average of 4 runs each; Westbury’s average was 5/wicket. The side won the Kidderminster League four years in a row from 1908-1911 and again in 1914 when they did not lose a match. Their run was only halted by the First World War when the league was suspended.

Fortunately the cricket team is still much in evidence. Whilst the side before the Great War can reasonably be regarded as a “golden generation”, their successors over the next 100 or so years also achieved (and continue to achieve) much success.

Photographs

At the end of June (2009), Alan Watkins and Graham Westwood organised a day for showing old photographs in the Severn Centre, with the help of Sally Bunn and myself. Graham has a site on the internet on Facebook at which he displays old photographs of Highley; Sally has an extensive collection of folders in the library.

Photographs are very valuable historical documents; a good photograph is also fascinating to look at. Photographs give a pictorial insight into a vanished moment in time and can be evocative and informative in a way that a bundle of writings can never be. However, photos are also easily thrown away, on the grounds that they are of no interest. It is true that family photos or snaps of friends may appear to be of no interest to anyone other than those in them, but sometimes the things included in the background of the photo can be very revealing.

The first photograph is of Mary Oliver taken some time  in the late 1940s. For me, the interest lies in the background—Ash Street in Garden Village. The old electricity pylons put up by the SWS Electricity Company are clearly visible; many will remember these, painted green and white. Ash Street had a much more uniform appearance in those days, when all the houses were held by the Highley Mining Company or the National Coal Board. However, for me, the most interesting item is a blurred structure by the side of the road, to the right of Mary. It is indistinct, but it is a water tank, built in the Second World War to supply the fire engine if there was ever a fire in Garden Village. I had read about the construction of this tank; it was discussed by the parish council and the reports of their meetings were carefully reported in the local newspapers. However, until I saw this picture, I did not know where it was built or what form it took.

in the late 1940s. For me, the interest lies in the background—Ash Street in Garden Village. The old electricity pylons put up by the SWS Electricity Company are clearly visible; many will remember these, painted green and white. Ash Street had a much more uniform appearance in those days, when all the houses were held by the Highley Mining Company or the National Coal Board. However, for me, the most interesting item is a blurred structure by the side of the road, to the right of Mary. It is indistinct, but it is a water tank, built in the Second World War to supply the fire engine if there was ever a fire in Garden Village. I had read about the construction of this tank; it was discussed by the parish council and the reports of their meetings were carefully reported in the local newspapers. However, until I saw this picture, I did not know where it was built or what form it took.

The second photograph is rather earlier, from about 1930, although taken very close to that of Mary. It shows Bob Poyner with a very young George Poyner on the bicycle handlebars. It was taken on the Orchard, again at Garden Village, but in the days when it really was an orchard and not the well-manicured green that now exists. Again, the background is blurred but the trees and rough state of the road can clearly be seen.

The second photograph is rather earlier, from about 1930, although taken very close to that of Mary. It shows Bob Poyner with a very young George Poyner on the bicycle handlebars. It was taken on the Orchard, again at Garden Village, but in the days when it really was an orchard and not the well-manicured green that now exists. Again, the background is blurred but the trees and rough state of the road can clearly be seen.

The final photograph is the earliest of all; probably about 1910. It shows Arthur Jones, steward of the Working Men’s Club and James Jones, a deputy at the colliery. They are at the back of Silverdale Terrace holding a newly killed pig. Pig keeping was very important to many families in the first part of the 20th century; the pig would be killed and cured to provide a store of bacon for months into the future. Many people still remember the ritual of pig killing, but this is the only local photo which I have ever seen that shows it taking place.

It shows Arthur Jones, steward of the Working Men’s Club and James Jones, a deputy at the colliery. They are at the back of Silverdale Terrace holding a newly killed pig. Pig keeping was very important to many families in the first part of the 20th century; the pig would be killed and cured to provide a store of bacon for months into the future. Many people still remember the ritual of pig killing, but this is the only local photo which I have ever seen that shows it taking place.

I am sure there must be many photos such as these still about, where the interest is in the background.

The war in the air

The Second World War was notable for the way civilians became involved; it was really total war. Of course, there had always been civilian casualties in any war fought in this country, but the Second World War was unique in that whilst there was no fighting in Britain, air power and particularly the use of bombers, meant that civilians found themselves directly under attack. To a very limited extent this had been seen in the First World War; I have been told that a Zeppelin found its way to Kidderminster, but this was a one-off. The effectiveness of bombing had been graphically demonstrated in the Spanish Civil War a few years before the Second World War started; few were under any illusions as to what was likely to happen.

Of course, Highley was hardly a prime target; it was widely anticipated that the main cities would bear the brunt of the bombing campaign. Indeed, perhaps the main impact of the air war was the arrival of large number of evacuees from Liverpool, shortly after war was declared. Some of these stayed longer than others; there is little doubt that they were safer in Highley than in Liverpool.

However, this did not mean that Highley was without any risk. Planes could veer off target or become lost; under these circumstances they would not be over particular at jettisoning their bombs wherever they could to lighten their load and get back to base. Bridgnorth suffered the consequences of this; bombs were dropped on Squirrel Bank and St Leonard’s Street; the latter produced fatalities. As a result, the village had to be prepared.

A team of Air Raid Precaution (ARP) wardens was formed, under the leadership of Richard James, one-time undermanager of Highley Colliery and landlord of the Ship Inn. These were responsible for enforcing black-out regulations and for monitoring for any bombs that might fall in the neighbourhood. The ARP wardens held regular drills, sometimes conducted by Lt George Davies of the Home Guard; they were marched round Netherton. Houses in the village had black-out blinds: especially thick curtains to stop any light from showing through windows. These continued to do service in many households long after the war.

A fire brigade was formed in the village in the summer of 1940 and had its own fire engine. The brigade itself had a high reputation for efficiency; they once beat the regulars in a competition. Unfortunately, in Highley they regularly had to battle against inadequate water supplies; it was perhaps as well they never had to attend a major incident in the village itself.

In 1940 the Women’s Institute petitioned for a public air raid station, to be located by the school. This was never built. Instead, people had to shelter as best as they could in their own homes. Children were often dispatched into the “glory hole”, a cupboard under the stairs, widely considered to be the part of a house most likely to remain standing in the event of a bomb strike. The sounding of the air raid siren unfortunately became a regular feature of nights during a large part of the war, as bombers passed in the vicinity en-route to Birmingham or the north-west. The nearest the village had to a strike was when a bomb was dropped in a field just by the Kinlet turn; the crater is still visible. This caused great excitement amongst local children as they then mounted a search for shrapnel as souvenirs; for veterans of the First World War, the sound as the bomb dropped and then exploded must have brought back raw and unwelcome emotions. Night after night these same men had to battle lost sleep as they then did their shift at the pit.

Of course, the country was not defenceless against the bombers. In the early part of the war, the planes were tracked by searchlight batteries. These were manned by regular soldiers. There were at least two of these in Highley; one down the New Road and the other by Vicarage Lane. There was also a mobile battery that ran on the road between Highley and Bridgnorth. They were eventually made redundant by radar, but they again brought the war home; they frequently identified aircraft in their beams. The soldiers slept next to the batteries in Nissan huts and some played football in the village team. Incredibly, one of the Nissan huts still survives as a barn, now on a small holding on the Clee Hill.

The coming of the motor bike

The 20th century is of course noted for, amongst other things, the spread of the motor car. Whilst the first vehicles were introduced at the end of the 19th century, cars first became prominent in the years before the First World War. Developments in engineering brought about by the war led to a massive increase in car ownership thereafter. However, cars remained expensive and, for most people, the first experience of motorised private travel was likely to have been a motor bike.

The pedal cycle was largely a late Victorian development. By itself, it significantly increased the range over which people could travel, both for work and for pleasure. At the start of the 20th century, small petrol or oil engines were developed for use in shops and in the home and it was easy enough to fit one of these to the frame of a bike. A brand new motor bike could still cost well over £50, but it was still significantly cheaper than a car. Given the indifferent state of roads which were little better than dirt tracks, a motor bike might also be a more practical proposition than a car. In Highley at the start of the First World War, there were far more motor bike owners than car owners.

The first person who I know to have had a motor bike in Highley was James Aston, who kept the New Inn. He purchased a motor bike in 1908 and a few years later traded it in for another, this time with a sidecar. By 1910 one of the village doctors, Dr Llewellyn, had also acquired a motor bike although he also retained a horse and trap for more sedate transport. Borle Mill bank provided a stiff test for any form of transport but in 1912 this was considered a positive attraction when it was the scene of motor bike trials. As far as I know, these were not repeated but they must have been quite a spectacle for the villagers.

Given their expense, the early motor bikes were not particularly aimed at the young. In 1912 the village wheelwright, John Derricutt, thought about buying a machine. He was now into middle age, but a bike would allow him to get about much more easily; he did work as far away as Chetton and Eardington and so transport was important. He first turned his attention to a number of second-hand machines, advertised in a motor-cycle magazine. Nothing seems to have come of this, but a year later he turned to the Colemore Cycle Depot in Birmingham, one of the leading suppliers in the West Midlands and ordered an Ariel motor cycle. Ariel was a local manufacturer and their machines were very popular in the years around the First World War.

Regrettably, his first experiences of the Ariel were not happy ones. The bike arrived in August 1913. In December he wrote to Colemore:

“II regret to say that the bicycle did not turn out to my satisfaction. The first time I rode it 8 miles from home a broken inlet spring – second time plug would not spark and 3rd time perfectly loose handle bars through a defective bolt in the same threw me over the handles and sprained my ankle and fractured the bone, 3 weeks in bed and on crutches –next ride that patched up front cover gave way and I had to replace a new Dunlop at a cost of £2-4-0. Owing to sprained ankle and fracture I was unable to go out with the cider machinery and lost over £30.” Perhaps surprisingly, the Colemore Depot were able to placate him; they may have fitted a new engine to the bike. In May 1915 he wrote, this time to Michelin:

“Kindly send your catalogue of motor cycle accessories such as tyres, retreading same, belts, tubes etc. I am thinking of stocking them as a side line as several of my friends ride motor cycles and I often repair same.”

Unfortunately, this enthusiasm for the motor bike was brought to a premature end by developments in the war. In July 1916 he wrote to a relative: “I hope to have the pleasure of seeing you on Sunday next if I can get any petrol. I am bringing Frances [his daughter] on the back for a run… we may not get any petrol, I have none yet for the engines in the shop. Government has stopped the sale of it”

Petrol rationing had been introduced the month before. For John and all the other village motor cyclists, it was back to push bikes until the end of the war.

The coming of the motor car

Last month, I wrote about the early motor-cyclists in Highley; this month I want to look at the first cars.

Early motor cars were expensive and probably gave uncomfortable rides on roads designed for the horse and cart. Nonetheless, in terms of speed, they could out-perform anything drawn by a horse or the pedal cycle and they could also carry more than a motor bike. The first cars seen in the village probably belonged to motoring enthusiasts from elsewhere. In 1911 there was a report of a “freak” accident at the Hag with a motor, but unfortunately there are no more details.

The first person in Highley to own a car was probably one of the two doctors who worked here before the First World War, Dr Kelly, who was remembered as having a Model T Ford. In July 1913, when the village wheelwright, John Derricutt, was buying a motor bike from the Colemore Cycle Depot in Birmingham, he also asked them for a catalogue for cars as he had a customer who wanted to buy one. A few days later he wrote back saying that Colemore had lost the sale as his customer had now had a trial with a car from elsewhere. There is no clue as to who this person might have been, but it is possible that it was Dr Kelly. Whenever the Doctor bought his car he could have kept it for no more than a few years, for in August 1915 he sold it and bought an AJS motorbike instead. Petrol rationing in 1916 probably stopped all private motorists in their tracks.

During the war, motor vehicle design advanced rapidly, as did the number of people capable of driving such vehicles. By the early 1920s a number of villagers had cars. Sometimes the village blacksmith, George Robinson, carried out minor repairs and recorded this in his ledgers. In 1919 he provided two stays to a car owned by Mr Winnall and in 1923 he repaired a mudguard for Clarence Swift, who ran a bakery in the High Street. This must have been for a car as in the same year Clarence was caught speeding.

Nonetheless, those who grew up in the village in the 1920s and 1930s remember the roads as very quiet; a car or lorry was a rare sighting. My guess is that in the late 1930s there were perhaps around 20 or so private cars in the village. Perhaps not surprisingly, they were usually owned by the better-off villagers. Mr Smith, the headmaster, had what is remembered as a very smart green car. Mr Brown, signalman and also part-time bookie, bought a car from new. Albert Billingham had a car which he used to deliver newspapers to the Clee Hill. John Perry, manager of Kinlet Colliery had a car; he is remembered as putting down newspaper on the seat before once giving a lift to Jack Poyner, the onsetter at Kinlet Colliery. The cars at this period were usually Morris’s, Austins or Fords. However, there were some more exotic models; Clive Grainger owned a Morgan.

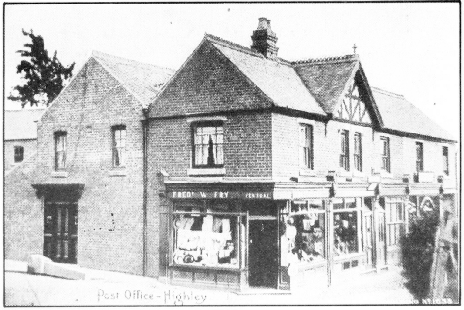

The car owners needed petrol to run their vehicles. In the very early days, it seems likely that they would simply purchase this in cans; John Derricutt obtained petrol in 1916 from Lloyds, the main shop in the village and as late as 1930 purchased four cans of petrol from F. W. Fry, who had the post office and a shop on what is now the car park in the middle of the village. However, in 1926 Fry had been given permission to install a petrol pump next to his shop and another, unnamed trader was given permission to put up a pump in 1930. By the mid 1930s there were petrol pumps at Fry’s, at Glen Cottage which was then owned by Whittles, and in Clee View, at Honeybourne’s garage. This has of course only quite recently closed.

Car ownership of course expanded quickly after the Second World War. However, even in the 1950s, it was possible to take advantage of what were, by today’s standards, very quiet roads. One car was much favoured as transport by some members of Woodhill Cricket Club in the late 1950s; it was nicknamed “Sputnik”, after the Russian space craft launched in 1957. This was purchased from Stourbridge by a local man who had never driven a car before. To get it back, he persuaded a friend to tow him all the way; he managed to steer the unpowered vehicle from Stourbridge to Highley without incident. Those were indeed the days of open roads.

Morris Minor

Morris Minor

c. 1931

The War Memorial

This May (2011) marks the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Royal British Legion and November will see the 90th anniversary of the first Poppy Day. In Highley, next June will mark the 90th anniversary of the dedication of our war memorial, in the churchyard. In the light of this, it seems appropriate to tell something of its history and surrounding events.

Around 100 Highley men fought in the First World War and by 1919 they had been demobbed and returned home. In early June, many of the veterans formed a branch of the Comrades’ Club. The Comrades of the Great War had been formed in 1917 as an association for soldiers and ex-soldiers and was one of a number of such organisations that grew rapidly when the war ended. The Highley Comrades elected Charles Nicholas as captain, A.W. Wilson as treasurer and Jack Ransom as secretary. This list of officials by itself raises questions.

Ransom had a distinguished war record and was the only Highley man to be awarded a gallantry medal. However, Nicholas was the colliery manager; he had played an important role in organising the Volunteer Territorial Corp, the First World War equivalent of the Home Guard, but he had never seen active service in the course of the conflict. The comrades invited veterans of the Boer War to join them, formed a sports committee who organised a boxing match and began to raise funds for a clubroom. The next week there was a public meeting to discuss how the village should celebrate the peace; at this Ransom complained that so far nothing had been done for the ex-service men.

In the event the following month there was a meal for them followed by a concert, apparently organised by the parish council. In November, the first anniversary of the armistice was marked by the comrades, although by now their secretary was Harry Ankers. Shortly afterwards they put forward plans for a war memorial in the form of an institute in the village. It is not exactly clear what they had in mind but it sounds like a fore-runner of the Welfare Hall. It would cost £1000, but the parish council agreed to support it. One year later, £350 had been raised, the cost had risen to £1200 and the scheme was abandoned. There are no further references to the Comrades; it seems likely that they disbanded.

It was to take another two years for a war memorial to appear in the village, and this was the cross that stands in the church yard. It cost £230, perhaps coming from the money previously raised for the institute. The memorial came from Lichfield by traction engine which duly became stuck on Borle Mill bank; not an uncommon occurrence. It was eventually manhandled free and was able to complete its journey to the churchyard. The dedication itself took place on July 12th. The memorial was unveiled by Major General Sir Archibald Montgomery of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, the local regiment. There was a procession from the cricket field (now the Rec) to the church led by the Brass Band, with the Rev Shields from the church and the Rev Wilkinson of the Methodists. The address was given by the Archdeacon of Ludlow. The ceremony itself was not unlike the current act of remembrance; the hymns were “O God our help in ages past” and “Peace, perfect peace”; the national anthem was sung, wreaths were laid and the Last Post and Reveille were played by buglers from the local Territorials, who had a company based in the village.

The memorial of course was immediately the focus of Armistice Day events. Thus in 1926 it was the destination of a parade formed by the Brass Band, the Buffs (formed in 1924), the Oddfellows (a village club), the Highley Working Men’s Club, the Woodhill Working Men’s Club and the ex-service men.