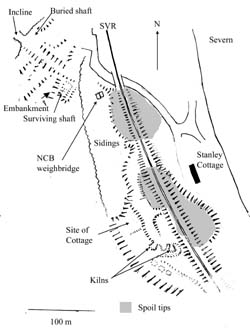

Industry in Stanley

(These features were recorded shortly before the site was levelled for new construction.)

(These features were recorded shortly before the site was levelled for new construction.)

.

The “Engine House”, the new museum for the Severn Valley Railway, is built on the site of the former Highley Mining Company sidings, opposite Highley Station. This was latterly a landsale yard for coal from Alveley Colliery, although it was constructed in the early 1880’s when Highley Colliery was first opened. In fact, the history of the site goes back much further than this and the ground clearance works have brought a number of interesting features to light.

The sidings themselves were connected to Highley Colliery by a rope-worked incline; full wagons of coal descended to the sidings and hence the railway, pulling empties back up to the colliery. The route of the incline is now the footpath linking the Country Park car park with the station and a section of old track can be seen by its side, together with some lengths of wire rope. At the station end, the track goes through a deep stone cutting. The oldest industry in Highley is stone quarrying and the stone ridge has been extensively worked. Indeed, the rock face which can be seen at the bottom of the incline may be part of a medieval quarry. Further along are quarries which date from the end of the 18th century and which were worked into the 19th century. These are impressive, with 50' high rock faces, in some places still showing the marks made by the picks and chisels of the quarrymen. Stone blocks were split off by “plug and feathers”; chisels were used to cut holes about a foot deep every 12 to 16 inches. A series of wedges were then driven into these holes, until a block of rock split off the face. In several places, these holes can still be seen on the rock faces. Other holes on the rock were created not by the quarrymen but by the Home Guard; the face of one of the quarries was used as a rifle range and is scored by bullet marks.

Some 80 years before the Highley Mining Company, coal was being worked in Highley at the Stanley Colliery. This covered the banks of the Severn between Highley Station and Stanley Cottages. One shaft is still visible; where the incline from the Highley Colliery now finishes, about 10 yards to the south. A small spoil tip associated with this has been removed as part of the recent ground investigation works, but the shaft itself has been spared. It is to be hoped that a proper archaeological investigation of this historic mining site will take place before it is further damaged; it is associated with some intriguing earthworks of unknown function.

Further evidence of the mine can be seen closer to the river. A large spoil tip behind Stanley Cottage is part of Stanley Colliery. This spoil tip can be traced on the other side of the railway. Nestling between the railway embankment and the spoil tips of the stone quarries is a fascinating patch of ground, untouched since the arrival of the railway at the end of the 1850’s. There are the remains of a cottage and outbuildings, once occupied by a miner at Stanley. There are also two circular brick pits. At first glance, these resemble colliery shafts but they are too close together and the bricks they are made from have been exposed to great heat. A clue to their function comes from the parish register of 1815, which shows Richard Rowley, a limeburner, was living in Highley. The structures are his two limekilns. He would have used coal from Stanley Colliery, literally a stone’s-throw away. He may have used limestone from Arley although it is also found outcropping close to his kilns. The lime he produced may have been used as fertiliser on the land, but would also have been used for mortar at the colliery. It is to be hoped the kilns are not destroyed in the construction of the engine shed.

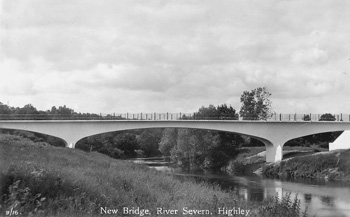

Alveley Colliery bridge

(This bridge was built by the Highley Mining Company in 1936/7 to link their new mine at Alveley with the Severn Valley branch of the Great Western Railway. It is shown new in this picture. It was demolished in 2006.)

(This bridge was built by the Highley Mining Company in 1936/7 to link their new mine at Alveley with the Severn Valley branch of the Great Western Railway. It is shown new in this picture. It was demolished in 2006.)

The old Alveley Colliery bridge was given a temporary reprieve back in September, when engineers decided that it was too risky to work on its replacement over the winter. Thus it seems likely that it will survive until this August. There is perhaps some irony in the fact that back in 1936/7 it was built in under a year and work continued all winter with no serious mishaps. The key to this was the way in which it was built, as a “balanced cantilever”. Essentially, this means that it was designed as a see-saw. The bridge has three arches; a large one in the middle over the river and two smaller ones either side to connect with the access roads. These are the “land arches”. The bridge was designed so that all the weight rests on the two piers that are either side of the river. The land arches run from these to walls that support the access roads and hold back the approach embankments; the abutment walls. However, these were designed so that they did not carry any of the weight of the bridge, they simply supported the approach roads. The key part of the structure was the two parallel reinforced concrete beams that ran continuously over the piers from Highley to Alveley and which supported the deck (the surface of the bridge over which people walked). As long as the reinforcing held, the bridge was safe.

The bridge led an uneventful life until the 1960’s. However, the Severn Valley is a notoriously difficult area for buildings. The ground is unstable, frequently slipping towards the river. This had started to take its toll on the bridge; the pressure of the ground was forcing the piers into the river. In addition, the abutment walls had cracks and the deck of the bridge was worn and needed replacing. Thus in 1967 the Coal Board decided it needed major repairs.

The main work was to stabilise the base of the piers. Coffer dams were constructed and the ground was built up to help the piers resist the thrust from the side of the banks. This part of the work passed without incident. The abutment walls were demolished and work started on rebuilding them. Again, this went smoothly, although the bridge apparently flexed visibly when heavy machinery was working on it whilst the abutment walls were missing. The deck was removed with pneumatic picks. Unfortunately, over the Highley land arch, the picks went in too deep and exposed a joint between the reinforcing rods in the beams that supported the deck. The joints failed spectacularly, the concrete cracked and the beams fell several feet at their landward ends until they came to rest on the partially rebuilt abutment wall. It is believed this incident caused a certain amount of panic at Coal Board Area HQ. Ladders were rigged up to allow men to pass over the dropped beams; without this, an entire shift would have been trapped on the Alveley side of the river. The beams were lifted back into more or less their correct place by jacks and the abutment was hastily rebuilt to support them. There was still a difference of a few inches between the top of the beam and the level of the approach road from Highley but this was made up by increasing the deck thickness with concrete from 6" to around 9". The repaired crack was carefully monitored but there is no suggestion that it has moved.

The excitement with the deck replacement meant that the repairs were not finished until October 1968. They meant that the bridge was no longer a balanced cantilever. By the time they were complete, the colliery was in its death-throes, closing in January 1969. Thus ended one of the less cost-effective jobs undertaken by the Coal Board in the West Midlands. It may however be suspected that the Area Engineer’s office was pleased to be rid of the bridge with its now unorthodox structure.

Highley Miners’ Welfare Hall

(This picture of the Welfare Hall was probably taken in the 1950’s. The sheep grazing the recreation ground give the scene a bucolic feel.)

(This picture of the Welfare Hall was probably taken in the 1950’s. The sheep grazing the recreation ground give the scene a bucolic feel.)

At the centre of Highley is the Recreation ground, now the home of the Severn Centre. Until 2005 this was the site of the Welfare Hall. The “Rec” and the Welfare Hall are a legacy of the local mining industry.

To trace the history of the Welfare complex, it is necessary to go back to 1920. In that year, the government set up the Miners’ Welfare Fund, to finance community improvements in coal mining areas. The coalfields were divided into districts and each mining community had its own local welfare committee which could apply to the appropriate district committee for funds for projects. The money came from three sources: a 1d/ton levy paid by the mine owners for every ton of coal they sold; a levy on the coal owners of 1/- for every £1 they received in royalties from coal obtained under their land; and a weekly voluntary contribution from the miners. Initially, the Shropshire District Miners’ Welfare Fund concentrated on providing recreation grounds. In 1923 the Highley Miners’ Federation obtained the agreement of the “squire”, John Oakley Beddard, and the village cricket club for the cricket field and the adjoining patch of land called Priests Pool to be turned into a sports ground and children’s play area. This project was approved by the Welfare Fund in Shrewsbury. However, it was to be another seven years before the project was completed and the “Rec” was born, probably because of cost.

In August 1930, according to the Kidderminster Times, Mrs Robinson, the wife of the doctor, organised a meeting to discuss the formation of a youth club in the village. The colliery manager, Mr Nicholas, was in the chair and the Highley and Kinlet Miners’ Welfare Committee agreed to provide a site free of cost. When the “Rec” itself was opened a few months later, it was noted that “space has been left for the road for a young men’s institute”. This was presumably for the Welfare Hall, although the Shropshire Welfare Fund was already keen to add halls to the recreation grounds it had developed across the county. The “Rec” itself consisted of a cricket pitch with pavilion, two hard tennis courts and two grass courts. There were flower beds either end of the pavilion and there was also the children’s play area with space for a “bandstand with promenades and putting and croquet lawns”. These were never built, but a bowling green was added in 1944, probably on the site of the grass tennis courts. The whole development cost £6500 and was constructed by Messrs Bakers of Codsall. It was opened by the general manager of the Highley Mining Company, Harry Eardley, on September 27th 1930, a week after the planned ceremony was abandoned because of rain.

It took another three years before the Welfare Hall arrived. This was built by Lacey’s of Kidderminster and was described as “a hall to seat 260 people constructed of timber framing, roughcast on metal lathing and lined with matchboard and insulated boarding”. It had brick foundations and asbestos roof tiles and cost £1892, including furnishings. It was the third welfare hall to be built in Shropshire, the previous ones being at St Georges and Ifton. As originally built, there was an open veranda on its west side, facing the playing grounds. This was subsequently enclosed, a move that no doubt was justified on practical grounds but which did nothing for the appearance of the building. A porch was also added.

In its early days, the Welfare Hall faced competition from other halls in the village, particularly the Assembly Rooms, just above the New Inn (now the Bache Arms). However, as a large, modern building, it soon established itself as the venue for meetings, dances and social events. For example, in August 1934 over 300 children of members of Highley Co-Op assembled outside the store and marched to the “new hall” to be entertained. Miners’ meetings and safety lectures were held in the hall. In the Second World War, dances following the Highley Nursing Cup featured the Alpha Dance band, J. Newey and his Paramount Dance Orchestra and Highley Brass Band. Generations of Highley folk have met and been entertained in the Welfare. Hopefully the new Community Centre will be as successful.

The Welfare Ground probably represents the single most important legacy of the miners to the present community of Highley. If it were not for their efforts in the 1920’s to acquire the land for the village and the work of subsequent years to maintain it, then the present new facilities would not have been possible. Mining was dangerous work. It is appropriate to record the names of those miners who were killed in the local mines; the Welfare Complex owes its existence to their and the their colleagues’ efforts.

Billingsley Colliery 1871-1921

Henry Berry

Thomas Homer

Charles Musgrove

Highley Colliery 1878-1969

Levi Price

John Weir

Henry France

John Hodgkiss

Alfred Davis

William Dudley

Norman Evans

Henry Sankey

Thomas J Hayes

John Hart

William Pope

Thomas Richards

William Kinersley

Alfred Hyde

George Amphlett

Owen T Owen

Arthur Jones

J Kesley

Wilfred Hayes

J Breakwell.

Kinlet Colliery 1892-1936

William Ernest Smith

Isaiah Geary

William Jones

William Tolley

Albert Patch

William Hart

Herbert Unit

Walter Andrews

George Eames

Charles Bishop

George Davies

Chorley Drift 1922-8

Arthur Lebeter

Alveley Colliery 1935-1969

Bert Bliss

Charles Brewer

George Turner

Victor Bow

Samuel Halliday

Colin Prime

Walter Raab

Richard Watkins

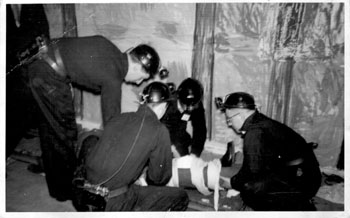

Colliery first-aid competitions

(Alveley Colliery Junior First Aid team in action in the Divisional First Aid Competition, about 1955. The team came second. From left to right; Bert Walker, Roy Bettridge, Des Poyner, Rolly Howe.)

(Alveley Colliery Junior First Aid team in action in the Divisional First Aid Competition, about 1955. The team came second. From left to right; Bert Walker, Roy Bettridge, Des Poyner, Rolly Howe.)

There is a traditional association between miners and sporting activities. In previous generations it was said that whenever England required a new fast bowler, all that was needed was for a selector to shout down a pit shaft in Yorkshire or the North Midlands and one would appear. Equally, the Lanarkshire Coalfield in Scotland was a production line for footballers who would later become legends as managers: Sir Matt Busby, Bill Shankley, Jock Stein. Highley was no exception to this; the local football and cricket teams were made up of miners and achieved great success. However, sporting spirit could manifest itself in other ways.

Mining was an inherently dangerous job. Fortunately, relatively few men were killed at Highley and there were no major disasters. None-the-less, there was inevitably a string of less serious incidents that left men injured. There was a constant need for men trained in first aid; where there were falls of ground, the mine rescue team would be required. Before the First World War, lessons in first aid were provided at the colliery and from 1912 a rescue team had to be formed at the pit. To keep both first aiders and the mine rescue team up to scratch, regular training was needed. As neighbouring mines throughout the country had their own teams of rescue men and first aiders, some rivalry between pits developed. And so was born the idea of inter-colliery competitions in first aid and mines rescue. This built team spirit and encouraged men to deepen their skills. Not surprisingly, the mine owners and Mines Inspectorate encouraged competitions.

From at least 1934 Mr Cain, the assistant manager at Highley, officiated at the finals of the Cannock Chase Coal Owners Mines’ Rescue Cup. With his interest in first aid, he probably encouraged Highley to enter competitions. In July 1939, in probably their first attempt, Highley were runners-up in the Shropshire Coal Owners’ Association competition. In 1940 three Highley teams took 1st, 2nd and 5th places in the competition. A photo exists showing the colliery first aiders posing outside the rescue station at Alveley, with the ambulance in the background and their cup in the foreground.

The competitions after Nationalisation are well remembered. These were in two phases. Firstly there was the area competition: effectively the pits in Shropshire and South Staffordshire. This was usually held at the rescue station in Dudley. Success here opened the way to the divisional finals, where teams from all over the West Midlands would compete. Both the rescue and first aid teams had considerable success. In 1950 Alveley came 2nd in the divisional rescue championship to Walsall Wood; the following year positions were reversed when they won the competition. In 1953 a new area junior competition for first aid was established, with Highley coming third. However, there were also individual awards and Bert Walker, the Highley captain, won this trophy. In 1955 the senior first aid team won the area cup and finished runners up in the divisional cup; in 1957 the juniors and seniors both won the area championship and the seniors finished third in the divisional trophy.

Mr Hasbury, the manager at Alveley, was keen for his teams to do well. This provided another incentive for taking part. Instead of working down the pit on a Saturday morning, the crack first aiders were more likely to be given time off to practise. The competitions, whilst keenly fought, were not without their lighter moments. In the first competitions, the casualties were not made up. Consequently one first aider was far from pleased to have points docked after setting a broken leg, only to be told by the judge that it was the other leg that was meant to be broken. The introduction of artificial blood, to make the casualties more authentic, stopped problems such as this but led to other difficulties. One local first aider, on investigating a casualty, got squirted in the eye by a stream of red liquid, allegedly from a severed artery. He was deducted a token number of points when the casualty shortly after cried out in pain; the judge assumed he had accidentally aggravated the injury. The deduction might have been more severe had the judge noticed that the first aider actually punched the casualty. This however proved remarkably effective at stopping the bleeding…

The pit ponies

(When Billingsley Colliery closed in 1921, the pit ponies were brought to the surface. This shows one of the ponies with Miss Grace Gibbs, daughter of Alfred Gibbs, the one-time owner of the mine.)

(When Billingsley Colliery closed in 1921, the pit ponies were brought to the surface. This shows one of the ponies with Miss Grace Gibbs, daughter of Alfred Gibbs, the one-time owner of the mine.)

The last pit pony in the country has now retired, bringing to an end a way of working stretching back over 250 years. Locally, Highley Colliery had over 50 ponies; including those employed at Kinlet and other mines, there must have been in excess of 100 ponies at work underground in the 1920’s and 30’s. Increased mechanisation meant that the number had shrunk to just 10 at Nationalisation in 1947 and by the early 1950’s they had all been phased out. None-the-less, they are recalled by many who worked down the mines.

The job of the ponies was chiefly to draw coal from the face, where it was mined, to the main underground roads which led to the shaft. These roads had mechanical haulage, but for many years it was not practical to extend this all the way to the working miners. It was not until conveyor belts were introduced, just before World War 2 at Alveley, that the ponies started to become redundant. The job of driving the ponies was given to boys, from 14 to 18 years old. For many of these, pony driving was their first job underground. It is perhaps not surprising that these youngsters, working alone for most of their time, often became attached to their ponies.

The ponies were kept underground for most of the year, in stables next to the pit bottom. These were whitewashed, warm, well ventilated and lighted. Each horse had its own stable with a nameplate; its gear was kept next to it. The stables were run by the ostlers. The last ostlers at Alveley included my grandfather, Jack Poyner. He was typical of the breed; a countryman used to working with horses and devoted to his charges. His fellow ostler, Job Hammonds of Chelmarsh was similar. They inspected the horses after each shift to check for signs of illness, injury or ill-treatment. They would groom the animals and make sure they were fed and watered. They would summon a farrier, if necessary, to cold-shoe the animals underground. The animals were brought up for the annual holidays; at the end the ostler with a small group of volunteers would round them up for the difficult journey back down the shaft.

The drivers were each allocated a pony. They would harness their pony and ensure that they were wearing a protective head guard that covered the top of the head and the eyes. The ponies were attached to a pair of iron shafts which in turn were attached to the draw-bar of the tubs which held the coal. The pony would probably have to draw several tubs, but this depended on where it was working in the mine. The pony was meant to be led from the side, but narrow roadways made this difficult. Many boys actually rode behind the pony sitting on the shafts; a dangerous practice as if they slipped they would fall under the moving tub. Training was usually non-existent, although they would normally start with “wide-driving”; driving the ponies along large roads rather than the very narrow roads leading to the face.

Individual ponies had their own personalities. Bonus was a particularly small horse-“almost human” and was exhibited at Stourport Carnival. Duke worked underground for 24 years. Jimmy was “a good puller but very slow”, Sambo was “very quick”, Turpin was “bad tempered”. Sparks would head for a manhole and then kick at his driver. Some drivers retaliated; Blucher appeared to have been hit around the head with a lamp because a later driver found he would shy away from a light. However, this seems to have been the exception and most ponies were much better treated than their fellows above ground. Whilst all welcomed the technology that finally allowed their retirement, many missed their companionship.

The Price of Coal

For some time, there have been comments around the village that there should be a memorial to the men killed in the local pits. From the later part of the nineteenth century it is possible to produce a fairly complete list, by reference to the reports of the Mine Inspectorate and looking through local newspapers. Here, I have simply listed those killed since the end of the First World War. Strangely the biggest problem I have is in recording the accidents from 1940 to about 1960; the Inspectors’ reports are not very detailed and I have not searched local newspapers. Accordingly, I have had to rely on people’s memories for this period; dates are sketchy and I suspect there may be omissions. There is also the problem of what constitutes an accident; I have left out one or two cases where individuals seem to have died at the local pits but through natural causes. Again, this is perhaps a matter for debate. I apologise in advance for any errors or omissions: I would welcome corrections so I can produce a more complete list. Even as it stands, it is clear that there was a fatal accident roughly once every other year at the local mines. It is little wonder that this shared danger produced the comradeship that many ex-miners now recall.

1920 Aug 14th Herbert Unit, killed by hoist on the surface, Kinlet

1921 Nov 19th Thomas J Hayes, killed on the underground haulage, Highley; Nov 28th Walter Andrews, Kinlet

1922 May 25th George Eames, killed by fall of roof, Kinlet

1923 Jan 19th Charles Bishop, killed by fall of side, Kinlet; June 20th Arthur Lebeter, killed by fall of roof, Chorley Woodside

1924 4th April, John Hart, killed by fall of side, Highley

1930 October, William Pope, killed by coal cutter, Highley; October, George Davies, killed by fall of roof, Kinlet

1932 Feb 20th, Thomas Richards and William Kinersley, killed by fall of roof, Highley

1933 Oct 6th, Alfred Hyde, electrocuted, Highley

1934 Jan 23rd, George Amphlett, onsetter, killed by fall down shaft, Highley; May, Owen T Owen, killed underground, Highley;

1935 Feb 20th Arthur Jones, Highley; July 6th J Kesley Highley

1937 July 26th Wilfred Hayes Highley, Sept 28th J Breakwell, killed by fall of roof, Highley

1947-59

Charlie Brewer, killed by striking his head against a bar underground, Alveley

George Turner, killed by fall of ground, Alveley

Vic Bowe, onsetter, crushed by cage, Alveley pit bottom.

1962 February, Samuel Holliday, killed by fall of ground, Alveley. November 16th Colin Prime and Walter Robb, shaft sinkers, killed by collapse of shaft, Alveley.

1963 July 5th Richard Watkins, killed by fall of ground, Alveley

The Landsale Yard

Many readers of the Highley Forum will be aware that opposite Highley Station are a pair of metal gates, leading into an area of waste ground, also visible from the footpath leading from the Country Park to the Station. Some of us can even remember when that was part of Highley Colliery and was served by a railway track that went across the road into a siding (I can only just remember it!). The area was originally developed as the sidings for coal wagons from Highley Colliery and it finished its working life as the “landsale yard”, effectively a coal yard where the local coal merchants could pick up coal for delivery by lorry. This area of land has now been acquired by the Severn Valley Railway and a few details of its history have recently come to light.

The industrial area of this site long predates the opening of Highley Colliery at the end of the 1870s. From 1804-1823 this was the site of the first large mine in Highley, Stanley Colliery. This worked coal at a depth of about 100 yards and this was sent by boat down the River Severn. The most visible relic of the mine is a spoil tip in the garden of Stanley Cottages. However, between the area taken for the Highley Mining Company sidings and the Severn Valley Country Park is an area of fossilised, early 19th century industry. There appears to be at least one shaft of the colliery still visible, with several spoil tips and traces of tramways. Here are also very impressive remains of the quarries that also worked at the same time, with a network of tracks and waste heaps. Today it is not always obvious what belongs to each phase of the site’s history, but hopefully with close examination more should be apparent.

The Highley Mining Company drove a railway from their mine down to the Severn Valley Railway in the early 1880s. The course of this is now the track from the Country Park to the station and passes through an impressive rock cutting. It was worked by rope haulage, with loaded trucks descending and pulling empties back to the mine. The landsale yard was created by dumping waste and spoil to form a level platform on which sidings could be laid. Initially shunting was done by horses but later some electric winches were installed to make life easier. Gravity was also utilised to help the shunters.

When coal winding was transferred to Alveley in 1940, much of the track was removed, but some sidings were retained for the use of coal merchants. There was a weighbridge and office (a tin hut) close to the entrance of the yard, where the coal was usually collected by horse and cart. Staff at the weighbridge were Sammy Howells and Charlie Link. When the National Coal Board took over, all this was swept away. Half the site was covered with tarmac, to improve access for lorries. A new weighbridge and office were constructed. The yard also seems to have been widened. In turn, the weighbridge complex was demolished when the pit closed in 1969.

The foundations of the NCB weighbridge and office have now been partially excavated. These have posed some questions! The offices are remembered as a timber building, set on brick foundations with a brick lavatory at the back. However, there seems to be a lot more brick rubble than would be expected from just this and a few yards from the offices, on the station side, more brick foundations have been uncovered. The office seems to have been partially built on a tarmac surface; this is overlain by a later coat of tarmac, which seems to have been put straight over a drain. Was the yard retarmaced at some stage? Why were the offices built half over the old tarmac? In front of the weighbridge there seems to be a brick pavement. When was this put down? Was it ever covered with tarmac? When exactly was the yard widened? Why was this done? And so the questions go on!

If anyone knows the answers to any of the above questions, either I or John Willis at Highley Station would love to know. Is it too much to hope there might even be a photo of the yard??

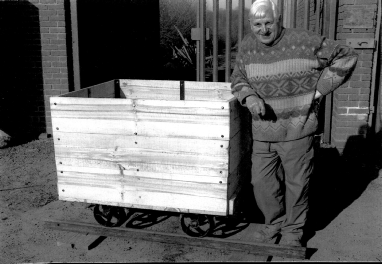

The tub-thumper’s tale

Most pictures of old coal mines include a few of the small railway wagons used to move coal from underground to the surface. These have a variety of names, but locally they were called “tubs”. They have a history as long as that of railways; the very first recorded railways in Britain in the 17th century were used to move coal and so crude, wooden wagons would have been needed. Not all mines used railways to move coal; some small mines used sledges and baskets well into the 20th century. However, these were exceptions; by the end of the 19th century a mine of any size would have had a network of railway tracks above and below ground. The UK coal industry was at its peak in 1913 when 1.3 million men were employed; there were probably something like that number of tubs.

It was possible to buy tubs from special suppliers, but more normally collieries simply bought the metal parts; two pairs of wheels with their bearings (called pedestals and spectacles), a central coupling bar, buffer hoops and assorted pieces of angle iron. The tubs themselves were made by the carpenters at the pit using wooden bodies. They were maintained in the tub workshop.

At Alveley Colliery in the early 1940s George Elcock, Almer Honeybourne, Fred Guy and Fred James worked in the carpenters’ shop, where they were joined in 1942 by George Poyner, a new apprentice. Jim Breakwell, Arthur Mayer, Stan Link and Dennis Mullard worked in the tub shop. New tubs were made by these men working overtime; they would be paid 12/- for each tub they made. Each new tub would be inspected by Mr Chesworth, the engineer, who would chalk WC on the side if they were correct. The tubs were made of elm boards, 1¼” thick for the bottoms and 1” thick for the sides, with oak sills to support the wheels and the body. The bodies were essentially boxes, 3’ x 4’x 4’. George Poyner would drill holes in the elm boards for George Elcock; for this he would get 1/- for the extra work. The boards were riveted together; Almer Honeybourne did this with a large lump hammer, although the process was difficult to carry out using cold rivets and these often needed further attention in the tub shop from Jim Breakwell. To tighten up the bolts that attached the sills to the bottom of the tub, a “dolly” spanner was used. Around 50 tubs could be produced in a week when they were needed.

About 1945 the decision was taken to replace the wooden tubs with metal-bodied versions, bringing to an end the job of tub-building. All wooden tubs were soon destroyed. However, recently George Poyner has built a new tub for display in the Severn Valley Country Park visitor centre at Alveley, as part of a new mining display. This uses parts salvaged from an old metal tub, whose body had rotted away. This has now been mounted on rails also salvaged from Alveley and is shown attached to a clip and next to a roller box; a scene that would have been familiar to anyone working at Alveley 65 years ago. The sheer size and weight of the empty tub is very instructive for those like myself who have not had that experience!

The Four Parishes Heritage Group are supported by the Local Heritage Initiative and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Nationwide Building Society.

The stallsman

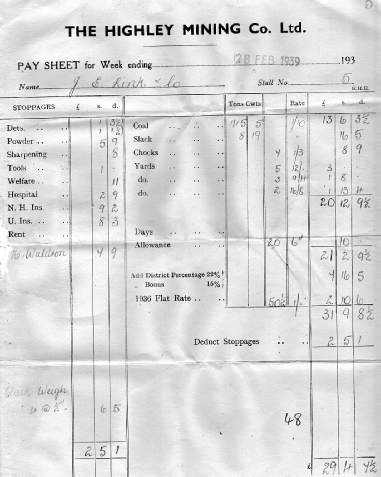

This article is based on a tin box of old papers that was found in an outhouse in Chelmarsh a few weeks ago. They are wages slips belonging to J. E. Link (John Ernest Link) who worked at Highley Colliery. They cover the period from 1935-1940 and they shed light on the work of the miners at that period.

An example of one of the wages slips is shown below. To follow it, it is necessary to know how coal was mined at Highley. It would be undercut by a machine along a stretch of 25 or more yards; this was the coal face. The miners were organised in teams, each responsible for a portion of the face called a stall; perhaps 6 or so yards long. They had to break the coal down and load it into small railway wagons called tubs to be sent out of the pit. Not all men did the same job. Some were loaders; they had to shovel the broken coal into the tubs. The more skilled task was to get the coal off the face (with explosives if needed) and then break it into lumps that could be shovelled into the tubs. This was the job of the pikesmen. In the 1930s the pikesman would earn a basic of 8/10¾ per shift against a loader’s basic of 7/6½.

However, neither loader nor pikesman was usually paid directly by the Highley Mining Company; they actually worked for one or more subcontractors who were responsible for the working of the stall. These men were called stallsmen; they were paid by the Highley Mining Company for the coal they got from the stall at an agreed rate. From this they would pay the pikesmen and loaders their basic, plus whatever bonus they decided and would keep the rest themselves. Mr Link was a stallsman; he shared No 5 stall at Highley with Hubert Waldron. At the start of the week they would have to judge how much coal they could get from their stall; this would depend on the exact geology they would encounter during the course of the week. Having decided that, they would agree with the deputy (the foreman) how many men they needed.

The slip for the 28th February 1939 shows that they were working in a very good place, for they raised 145 tons of coal and nearly 9 tons of slack, for which they got 1/10 per ton. To keep their stall safe and easy to work, they needed to build 7 roof supports (chocks), for which they were paid 1/3 each. The “yards” probably is the work they had to do to drive and maintain the access roads to the face; they were made to different widths and the payments reflected this. During the week it looks like they drove 10 yards of new road, as the face advanced. This gave the basic payment which was then multiplied by various percentages which reflected past pay rises agreed since 1912; the most recent was a 1/- a day rise won in 1936.Against this, the stallsmen were charged for all explosives and detonators used in blasting the coal down, the cost of sharpening tools, a payment towards the cost of the Welfare ground, a sum for medical insurance and also unemployment insurance. There was also a deduction of ½d for every ton of coal to pay the checkweighman; this was a person nominated by the miners to work alongside the company clerk, to ensure that all the coal was weighed fairly.

The slip for the 28th February 1939 shows that they were working in a very good place, for they raised 145 tons of coal and nearly 9 tons of slack, for which they got 1/10 per ton. To keep their stall safe and easy to work, they needed to build 7 roof supports (chocks), for which they were paid 1/3 each. The “yards” probably is the work they had to do to drive and maintain the access roads to the face; they were made to different widths and the payments reflected this. During the week it looks like they drove 10 yards of new road, as the face advanced. This gave the basic payment which was then multiplied by various percentages which reflected past pay rises agreed since 1912; the most recent was a 1/- a day rise won in 1936.Against this, the stallsmen were charged for all explosives and detonators used in blasting the coal down, the cost of sharpening tools, a payment towards the cost of the Welfare ground, a sum for medical insurance and also unemployment insurance. There was also a deduction of ½d for every ton of coal to pay the checkweighman; this was a person nominated by the miners to work alongside the company clerk, to ensure that all the coal was weighed fairly.

The pay slip shows that Messrs Link and Waldron were paid £29-4-7½. This was shared between themselves and 9 other men who worked in their stall. This was an exceptional week; normally they employed only 4 others. It looks like not every man worked all the theoretical maximum of 5¾ shifts in the week as only 50½ shifts were worked in total. On average each member of the team would earn just over £3; although if the stallsmen had done their calculations correctly they would hope to see nearer £4 as their profit. To get this money, each man had moved 3¾ tons of coal a shift. They would have done this on their knees, working in a height of 3’9”; the money would have been well earned.

Alveley pithead baths

Coal mining remains a basically difficult and unpleasant job, although over the years there have been many advances that have made the work more bearable. However the coal is cut at the face, it is inevitable that this will create large quantities of black dust that will cover everything, including the miners themselves. Indeed, even those not at the coal face will end up black from the dust. It is hardly surprising that for many years one of the demands of the miners’ union was the provision of baths at the coal mines where men could get clean before they went home. As a result of legislation in the 1920s, the Miners’ Welfare Fund was set up, financed by contributions from a levy on the price of coal, contributions from the mine owners and also a voluntary contribution from the miners and this funded the establishment of pithead baths, amongst other things.

When the new Alveley Colliery was opened in 1939, the local union was keen to see better facilities for the men. By 1941 a mobile canteen was present. Also in that year, the first pithead baths at a Shropshire colliery were opened at Madeley Wood. In 1944, the local union suggested that the construction of baths at Alveley would help productivity at the pit. Nothing came from this in the short term, but it was agreed that baths should be built on land then occupied by a saw mill. In 1947 the mines were nationalised but this still did not bring about the pithead baths. It was not until 1950 that they were finally built, designed by the architect J.H. Bourne.

The opening was considered a great event; Sir Ben Smith, the chairman of the West Midlands Division of the National Coal Board came to formally open them on Saturday March 4th and there were speeches from officials from the National Union of Miners, Ray Hasbury, the colliery manager and Mr Chesworth, the colliery engineer. The proceedings were carefully described in a printed booklet. Following the opening, the baths were thrown open to inspection by all those present. The following day, workmen and their guests were invited to look round, prior to use on the Monday. The arrangements for using the baths were also carefully explained. There was a “clean” entrance, used by men reporting for work. Once in the baths, each man had a heated locker in which they hung their clean clothes. They then moved to a second set of lockers, in which their pit clothes were stored. They changed into these, at the same time placing their soap and towels in these lockers. They then went down the pit; they could grease their boots and also fill their water bottles on the way out. After their shift, they entered the baths through the ‘pit’ entrance. They would first clean their boots on electric revolving brushes then go to their pit clothes lockers, to undress, collect their towels and soap and move to the showers. Once washed, they then went to the ‘clean’ lockers to dry themselves and change back into their clean clothes. The booklet contained many hints on how to get the best from the baths. Some, such as laying out damp clothes properly so that they would dry were sound, if obvious. Others, such as the injunction to finish washing in cold water to avoid catching cold, owed more to folklore than medical science!

The booklet, in addition to carrying instructions for using the baths, also had a number of adverts that have an interest of their own, some 60 years later. Preedy’s de luxe menthol snuff was apparently available from the canteen. Whittles Coaches, Blackham the village chemist and Pearson’s Stores in the High Street all advertised. However, my favourite is the advert for William Harris ‘high class meat purveyor’. At one point the advert turns to verse:

‘If by chance your Faith is shaken,

Don’t take Grief

Try “HARRIS”

For Beef, Pork, Lamb or Bacon’

The baths still survive as part of the Alveley Industrial Estate, together with a small sewage plant that treated the waste water from the showers.