Borle Mill

(Borle Mill was the site of Highley’s corn mill from the 13th century. This sketch was made in 1950 by Highley schoolmaster R. A. Martin for a dissertation on the village's history for his degree. The timber-framed portion in the centre remains the oldest surviving portion. The wheels were to the left of this structure. To the right, a new sandstone house was added in the late 18th century.)

(Borle Mill was the site of Highley’s corn mill from the 13th century. This sketch was made in 1950 by Highley schoolmaster R. A. Martin for a dissertation on the village's history for his degree. The timber-framed portion in the centre remains the oldest surviving portion. The wheels were to the left of this structure. To the right, a new sandstone house was added in the late 18th century.)

There are very few sites in Highley that can claim a documented history stretching back to medieval times. The Church is one such, but the site with the next longest recorded history is probably Borle Mill.

Whilst in early communities corn was milled by hand, during the middle ages there was a striking increase in the number of water-powered mills. Borle Mill belongs to this era. We do not know when it was first built, but in an order of nuns, the White Ladies of Brewood, were in possession of a tenement in Highley. This was probably the mill because in 1249 the Prioress sued Brain de Brampton of Kinlet for levelling a water course in Highley; presumably the mill race. The White Ladies would not have worked the mill themselves but would have let it out to a miller who would have paid them rent. In the middle of the 15th century this was William Lowe and the Lowes were to be associated with the mill for the next 200 years. The miller was an important man in any village and he had the opportunity to make a very comfortable living. The Lowe family made the most of this; they give the impression that they put upward mobility before popularity. By the middle of the 17th century Thomas Lowe had become lord of the manor and styled himself as living in Borle Hall. He was described as owning three mills; although this probably means there were three sets of grinding stones worked by one water wheel rather than three distinct mills by the brook. The middle, timber framed portion of the current mill probably dates from the times of the Lowes, although the hall has long since gone.

In fact the hall of Thomas Lowe may well have been demolished in the late 18th century to make way for the stone built house that now forms the main living quarters of the mill. It is not clear who built this; in the Eighteenth Century the mill was owned by a variety of influential village families including the Jordins (who later became the “squires”) and the Stewards who owned much property around Netherton. What is certain is that in 1783 the mill consisted of one wheel driving three pairs of stones (probably the same as Lowe’s mill in the 17th century) and an adjacent mill with a water wheel attached to just one pair of stones. These could be let separately, although in practice they were probably worked together. Today the end of the building nearest the road which used to house the mill wheels is made of brick and may well be of late Eighteenth or early Nineteenth Century in date.

Towards the middle of the Nineteenth Century the mill was owned by Daniel Jordin, a brother to “Squire” William. In the 1880’s it was put up for sale when it was stated that two wheels worked two pairs of stones, although there was room for two more stone. Following a period when it was leased to a variety of itinerant millers, it passed to the Derricut family at the turn of the century. At this stage it seems to have mainly ground corn and beans for animal foodstuffs; grain for bread was increasingly being sent to large mechanised mills. Soon even the foodstuffs market vanished as farmers purchased their own small mills. Just before the First World War the mill was purchased by the Evan’s family whose descendants owned and lived in it until recently. The mill became derelict and a sawmill was set up in the yard. Just after the Great War there was even a proposal to convert it to a hydroelectric power station. The end finally came in 1947 when the mill dam was breached by floods.

Although much has been lost, the recent renovation means that the core of the mill is now safe and once again is a family home.

Greenhall

(This painting of Greenhall was done by local miner and amateur artist, Wilf Turner, probably about 1920. The house pulled down in the 1930’s.)

(This painting of Greenhall was done by local miner and amateur artist, Wilf Turner, probably about 1920. The house pulled down in the 1930’s.)

It is in the nature of buildings for them to eventually decay and fall down. In medieval times, Highley was probably home to 30 or more families; the only building that survives from those days is the church. Similarly, most of the Tudor and Stuart homes have long since fallen down; those that remain are now considered to be important and every effort is made to preserve them. Unfortunately a few fall through the net. In Highley, the biggest loss has probably been Greenhall.

Greenhall is found down the footpath that goes from the Malt to New England. The site is now a bramble-covered mound; a few stone blocks mark tumbled-down walls. It is not much of a memorial to what was once one of the largest and most important houses in the village. The first house was probably built in medieval times. The north of the village remained covered by woods long after the rest of the parish had been converted into arable fields. Pioneer farmers were encouraged to clear patches of woodland to establish their own farms, on which they would graze cattle and sheep. Greenhall originated in this manner. The name incorporates the old English word, halh, meaning a small enclosure; a good description of the first isolated woodland clearing. Gradually it became more important; in Tudor times it is possible to see how it swallowed up the neighbouring estates of the Sturt and Jenkin’s Harries. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I it was occupied by the Holloway family who were amongst the wealthiest inhabitants of Highley; in 1587 it passed by marriage to William Pountney. Pountney at first leased the farm but bought it outright in 1609. Pountney was the largest landowner in the village at this period, also owning the Rea Farm. However, in 1639 William’s son, George, sold Greenhall to Stephen Edmunds In the later 17th century the house was divided into two, occupied by Stephen and his son-in-law, John Bates. At this period it was sold to the Fox family of Cleobury Mortimer and from then on was held by a series of tenant farmers.

Greenhall remained an important farm into the 19th century. However, early in that century a new farm was established at Woodhill. In 1858 Greenhall was purchased by the vicar of Highley, Samuel Du Pre; in 1859 he also bought Woodhill. Woodhill was a modern farm with relatively new buildings; within a few years the two had been amalgamated with Woodhill as the farmstead. Greenhall was now used as a labourer’s house. In 1871 it was occupied by John Hopkins, a waggoner who presumably worked at Woodhill. Twenty years later the link with the land had been broken when it was home to Christopher Foxall, a bricklayer. Later it housed a number of miners; including the Weaver and the Palmer families. At times it was subdivided and let as two homes. One of the last occupiers was Horace Cooper who was later to entertain many with his tales of a ghostly cavalier who was said to walk into the fireplace. After World War 1 the house fell into ruin. It was eventually demolished about 1935 by Pain’s of Cleobury; the end truss was pulled out by a tractor with a wire rope.

A few photographs survive to show what the building looked like. Local man Mick Cotton has used these to reconstruct the appearance of the house when it was built about 1600 by William Pountney. If any more illustrations of the house exist, please let me know!

The sale at Greenhall

There is a tendency to assume that, in past times, villages and the countryside were places where nobody moved and people spent all their lives in one place. In fact this was far from the case. Agricultural labourers were typically employed on a 12-month contract; at the end of that period they were not slow to move on if they could get better conditions elsewhere. Farms were usually held on longer leases but, again, there were usually either get-out clauses so the tenant could move or be ejected, depending on the circumstances. Whilst people could move fairly easily by horse and cart, transporting large quantities of furniture, livestock or other possessions was a much harder job.

Consequently, when a farmer moved on, he would normally sell many of his household goods and farming implements, only retaining a few items. It would be easy to buy replacements at his new place. Thus auctioneers were busy people. Records of some sales from these times are still in existence. The auctioneer’s clerk from the firm would visit the premises a few days before the sale and record every item that was to be auctioned, both inside and outside the premises. Often he would list items in individual rooms. Thus these records give a very detailed insight into the arrangement and furnishings of many old houses, as well as the equipment used on farms.

In August 1851, there was a sale at Greenhall in Highley, to dispose of the property of Vincent Homfray who was leaving. Greenhall stood in the north of the village, in the fields behind the Malt Shovel. As it was demolished in the 1930s, the room-by-room inventory taken by the clerk gives us a unique glimpse into a literally lost world.

The clerk started with the brewhouse. As its name suggests, this is where beer would have been brewed; most farms produced their own beer or cider and this was often part of the payment to the farm labourers. The brewhouse was sometimes a detached building; it is not clear at Greenhall if this was the case or whether it was within the main house. Brewing was carried on in this room as there was a mashing tub to soak the malt and a furnace to provide hot water, but it is clear that its main use was as a dairy. There were milk pans and churns, cream skimmers and pans and also a cheese press. Indeed, a number of dairy cows were included in the sale and it is likely that most of the milk would have been turned into cheese for sale. There were also stray agricultural items: rakes, pikels and a seed hopper.

Whatever the status of the brewhouse, there were clearly three main ground floor rooms: the pantry, the parlour and the kitchen. The pantry seems to have been a small storeroom; the contents included knives, forks and earthenware bowls, plates and cups. The kitchen would clearly have been where food was prepared but was also where many meals were eaten; there were two dining tables, one round and one a two-leaf folding oak table and six chairs. A large 8-day clock completed the main furnishings. The parlour was probably the best room; there was another two-leaf oak table probably used less frequently than that in the kitchen. It also had an 8-day clock, but there was a writing bureau where the farm accounts would be completed.

Upstairs there were three bedrooms. As Greenhall was a three-storey house, perhaps the third bedroom was on the uppermost floor. They were simply furnished. The best bedroom had a pair of beds, a pair of dressing tables, a small bedstead, a chest of drawers, an oak linen chest and a chair. The second bedroom had just one bed, a linen chest, table and chair, but did have a carpet on the floor. The final bedroom seems to have had two beds, but little other furniture. It did however serve as a store for swede seed!. Homfray lived at Greenhall with his wife and four children; there was also a farm worker who boarded in the house. The exact sleeping arrangements are now not clear; possibly not all the bedroom furniture was included in the sale. It is a fair bet that the farm worker had the least comfortable sleeping arrangements

This completes the inventory of Greenhall. There is however one mystery. Pictures of Greenhall show it to have been a large house and it is surprising that more rooms were not recorded. Perhaps some rooms were simply not used by Homfray.

The Stone House (1)

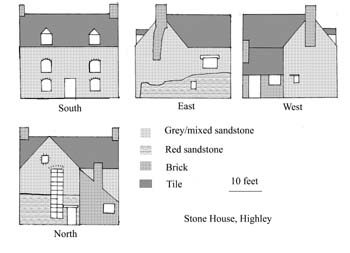

(These elevations were recorded prior to the demolition of the property in 2005.)

(These elevations were recorded prior to the demolition of the property in 2005.)

The Stone House in Highley has recently been demolished, to make way for new houses. As such, it seems appropriate to put down what is known about the history of this somewhat enigmatic house.

The Stone House first appears in the record in 1773, when a Richard Fosbrook paid rates for it. More details come in 1779, when the ‘Stone House and New England Farm’ were offered for sale. It was then a small farm in Highley with 15 acres immediately surrounding it and about another 30 acres in a detached block at New England. There were doubtless farm buildings at the Stone House itself but there was also a stone barn on the land at New England; the foundations of this survive next to a quarry. In the late 1790’s the occupier of the Stone House was Joseph Powell, a land surveyor. It is possible that the land was sublet to another farmer at this date. The land at New England was removed from the Stone House in the mid-19th century, passing to Hazelwells Farm and then Greenhall and finally incorporated into Woodhill Farm.

The Stone House was now a small-holding; in 1859 surrounded by 16 acres of meadow, pasture and orchard ‘well stocked with thriving fruit trees’. The house had ‘a good parlour, kitchen and brewhouse and six lodging rooms’. When William Stokes left the Stonehouse in 1882 the dispersal sale included 3 ricks of hay and clover, 3 dairy cows, a bay cob, a breeding sow and a bacon pig, a chaff-cutter and a washing machine and mangle ‘nearly new’.

By the start of the 20th century the Stone House was in the hands of Harry Fox. In 1913, the Billingsley Colliery Company, exasperated by opposition to their plans to build workers’ houses in Billingsley, decided to go for a green field site in Highley. The Stone House land met their requirements and soon the ‘well stocked orchard’ was a building site for Garden Village; all that is left of it now is the name. In the 1920s and 30s Miss Newey lived in the Stone House and used it for her school. A water tank was built by the house for Garden Village as well as workshops and a garage.

Can we take the history of the Stone House back beyond 1773? The house as it exists today is almost certainly largely 18th century: a typical stone farm house of the period with a cellar and plenty of rooms for farm servants. The land it was built on was originally part of the common grazing land of Highley; Higley Wood. This was enclosed and divided up amongst the main farmers of the village around 1620; in the subsequent 100 or so years a number built houses on their allotments and sold them on. This is what may have happened with the Stonehouse, perhaps with the house being built a little later than usual, around c1750. However, there is evidence for a much older house on the site. In 1591, John Nicholls held “Le Stone house”. If this was the same as the current Stone House, then it has left no obvious trace in the structure of the building. However, it was not unusual for the Lord of the Manor to allow tenants to build cottages on the common land of the manor; the tenant got a house and the Lord collected the rent!

There is one other example in Highley with a now-vanished house called Kingshouse, where this may have happened. Thus the Stone House may have originated in the 16th century or earlier as a cottage on the common land and then was completely rebuilt around 1750 to give the present house. Perhaps during the demolition of the current house we may get some clues as to whether an earlier building really existed here.

The Stone House (2)

Following the recent demolition of the Stone House, a few months ago I wrote an article about its history. In many ways, that article posed more questions than answers, particularly about its origins. Following some careful detective work in the archives it is now possible to give a much fuller account of the house.

The history of the house probably begins in Tudor times, around 1550. At that date, the land on which the Stone House was to be built was part of the common grazing land of Highley; an area called Higley Wood. However, the Lord of the Manor could usually earn more from rents of houses than he could for payments for common grazing and so there was always the temptation to allow houses to be put up on small patches of the common. This is what seems to have happened with the Stone House. We do not know who did this, but when the house is first mentioned in 1590, its earliest owners were John and Ann Nichols. They paid 6/8 rent a year for the cottage and 3½ acres of land. Ann inherited it from her father, Thomas Lowe, a barge owner and he may have built it.

Following Ann’s death in the early 17th century, there are no more references to the Stone House for well over a 100 years. However, 17th century pottery from around the area shows that the house was still being lived in at this date. It reappears in the records, albeit without a name, in 1708. In that year John James seems to have moved in. James was an upwardly mobile wheelwright and carpenter; records show how his household expanded to include both a man and a maid servant as well as his wife and children. The Stone House as it stood recently had no obvious trace of a Tudor cottage; it may well have been James who rebuilt it on a grander scale to suit his aspirations.

For the first half of the 18th century the house stood either alone or with just a few acres of land surrounding it; part of the old Higley Wood estate. However, in the second half of the 18th century, the land associated with the house expanded. This process seems to have begun in the 1760’s when a Richard Charter held the house. He rented two other estates in the village and so probably farmed around 50 to 100 acres. In 1772 Charter moved on and was replaced as tenant by William Lamb. At this point the Stone House became associated with about 30 acres of land at New England; together with the land around the house, this meant that the farm was about 50 acres. At this point the house and associated lands were held by the vicar of Highley, Dr John Fleming and for the first time in over 150 years the name “Stone House” was revived. Whatever the aspirations of John James, the 9 rooms of the Stone House in its final form would seem excessive for a wheelwright but more in keeping with a farm house. Furthermore, some of the features of the house seem to belong to the late 18th century. It is possible that James’s house was substantially rebuilt by Fleming.

For most of the rest of its history, the Stone House was occupied by a series of farmers. There is one more episode that is worth mentioning. In 1808 the house and land were rented by William Shield of the Bind Farm in Billingsley. Shield was one of the first Methodists in the area and the earliest Methodist services in the district were at his house. They subsequently were held at a cottage in New England before a chapel was built in 1816. However, his interest in the Stone House raises the possibility that he was considering using this as a chapel for Highley before other arrangements were made.

Coronation Street and the Bache Arms

(This picture, taken around 1905, shows the New Inn (now the Bache Arms) on the left, with the camera man looking south down the High Street.)

(This picture, taken around 1905, shows the New Inn (now the Bache Arms) on the left, with the camera man looking south down the High Street.)

Coronation Street was built in 1901 and was named after the Coronation of King Edward VII. It was built on a patch of land called Corbett’s Meadow. At the bottom end of the Street the Bache Arms, (originally called the New Inn) and the shop (Glen Cottage) predate the street and may have been built in the late 18th century, although they are now much altered. There may also have been a large medieval or Tudor farmhouse behind the Bache and Glen Cottage but this vanished by about 1820.

With the coming of the Highley Mining Company in the late 1870’s, the village grew rapidly in size. By the end of the 19th century more houses were desperately needed by the Company. Via a subsidiary called the Highley Land and Building they purchased land in the village centre. Orchard Street was built first, then Coronation Street, then Barke Street. A large tank at the top of Coronation Street supplied water to standpipes for the houses; beneath the tank there was a property repair workshop. (The tank was secondhand, having been made in 1866).

The houses in Coronation Street had a front room, a kitchen and a back kitchen downstairs. Upstairs were bedrooms. The front room was usually the best room. The back kitchen was where most work took place; it had a cooking range and a boiler for heating water. The kitchen also had a cooking range with a built-in boiler. The front room and (some) bedrooms had fireplaces. Outside was a (large!) coalhouse whilst at the far end of the yard was an earth privy with a seat made of polished pine. There was one ash pit per two houses.

As turn-of-the-century workers’ houses, they would have been considered quite reasonable; certainly much better than the old agricultural labourers cottages that made most of the rest of the villages housing stock. Water was fetched and stored in enamel buckets covered with wooden lids. Although only a single standpipe served the whole of the north side of Coronation Street, this was probably more convenient than a walk to a well to draw water of uncertain quality. Keeping the fires going for heat, warm water and cooking would have been hard work but the miners got plenty of concessionary coal. The privy’s were emptied once a week by the horse-drawn “chariot”. The houses were lit by candles or oil lamps. There were no gardens but within a few years many men had allotments. The houses were rented to miners.

Although life in the streets was comfortable enough when the houses were first built, they were made to look primitive by houses built before the Great War elsewhere in Highley. Modernisation had to wait over half a century. Piped water indoors did not arrive until the early 1950’s and water closets were a later still innovation.

The New Inn was rebuilt at the turn of the century. Under the long tenure of the Bache family it became one of Highley’s institutions. In the back yard the late Dr Wilkins built a wooden hut to serve as surgery for the village which remained in use until the 1970’s. Glen Cottage was also extensively rebuilt and became a grocers shop owned by the Whittle family. When the coach business started, the yard at the back was used as the garage, as well as serving as the stables for the horse for grocery business’s delivery float. Subsequently the shop passed to Bernard Price before becoming part of Bob Cowley’s garage. Many will remember the petrol pump that stood outside the shop.

Bargate, an old cottage

Younger folk and people who have come to the area in recent years may be surprised to learn there were once a number of riverside houses between Arley and Highley. One of them was Bargate or Bar-yat as the old people called it. It lay in Kinlet parish, one field’s length below Borle Brook.

I first saw Bargate on Good Friday 1936. My Aunty brought my cousin Doris (16) and myself (10) to spend the Easter holiday at Grandma’s new home. Railway services were restricted that day, so we had a long walk beside the river from Bewdley, but at last we crossed a little footbridge between trees and we had arrived.

The house, its steep grey roof and big brick chimney rising above the surrounding fruit trees, stood back from the river, in ¾ acre of garden and paddock. On the south side was the grass grown vestige of an old road to the river and the dry course of the brook, now diverted, that once marked the county boundary.

Aunty led the way up the path and unlocked the door. We stepped into a long room with a low beamed ceiling and red quarry floor. The room was furnished, so we were able to “flop” onto chairs and look round. There were two windows, the largest to the front but a third of it was hidden by a boarded projection and door that hid the stairs. A kitchen range was set in the centre of the inside wall and a door at the end. Aunty suggested that we look round whilst she lit the fire.

The door at the end of the room and a step up, led to a short passage, the inside of the wall being the side of the great chimney and hearth block around which the house was built. A deeper step down took us into another long, brick-floored room with two windows, one facing the river, the other south. One massive beam, studded with hand-wrought hooks and nails crossed the room. Deep into the dividing chimney wall was a large open hearth, its stone a gritty yellowish grey. We ducked under the big black beam that supported the wall above and looked straight up the chimney. A little further along the wall was the bread oven. The front window had a seat. The rough beam forming it was movable. Lifting it we saw the space between the inner and outer walls was filled with stone rubble and mortar. All the walls in this room were stone built, unlike the other room where the north gable was timber framed with brick filling, probably 17th or 18th century construction. Half the front wall was of brick too.

Aunty called us to take our things upstairs. The stairs were strange to us. Six or seven treads (no risers) were thick boards, worn smooth and polished by age. They were set in grooves made in the side and back boards. A square landing to the right, two steps with risers and another landing were of more modern construction. Posts and rails kept us falling down the stair well. Here we saw the chimney, most of it jutting into the north room. It narrowed with two “steps” roughly plastered. An alcove above the passage was wide enough for a double bed (5’6”-6’). The bedrooms were divided by a wall of wooden frame and planks. Unlike the north room, the south room had a door. It also had a fireplace, a smaller version of the one below (how was the hearth stone supported?). It was bricked in except for a tiny grate. The chimney above had a rounded slope back above before disappearing, the alcove at the side being only 2’ deep or so. The stone front and the entire brick wall were no more than 2’6”-3’ high and about 9” deep. The ceiling, lined with boards, slanted above us. The size of the rooms may be estimated when I tell you that this room had a double bed at each end and a 9’ x 12’ carpet did not cover half the floor.

Later, while eating a meal, Aunty told us the little she and uncle had heard of the house. Bargate was said to have been one of the oldest houses in Shropshire, also from its position on the river bank, the first house in the county and the old toll-bar and ferry cottage. The stone portion was much older than the 2 north rooms. Before the railway was laid the roof had been thatched but was replaced with tiles to avoid the danger of a fire. This was also when the stairs were moved and Victorian landings, bedroom wall and ceiling made, the range and bedroom grate fitted.

Later we were able to wander round outside. To one side there was a small stone building with two doors. This housed the earth closet and the pig-sty. We discovered a strange circular stone trough in the garden. What was it? It was some months before we were told it was the base of a cider mill.

We discovered Bargate’s big drawback, no water supply, very quickly. Aunty handed us a bucket and a gallon jug and sent us to the only spring we had seen on our long walk. It flowed from a spout under the railway bank below Arley Island, a very long field’s length away. Luckily we soon found the overflow from Severn Lodge well, between home and Brooksmouth and eventually Uncle found a tiny spring in the garden but it dripped slowly. We didn’t fancy river water, though Mrs Hannah Davies of Brooksmouth assured us “I’d as lief ‘ave a cup o’ tay out o’ Severn as anywheer”.

Bargate became a happy place for me. In 1940 it became a permanent home for me, for Doris the greatest happiness in her short life. After Grandma left in 1949 the house was modernised a little but it was soon empty again. It was vandalised, used as a cowshed and finally fell into ruin before being demolished. The last time I visited the site, the trees had gone, the garden added to the field and ploughed up. I found one piece of brick.

Peggy Lucas

New thoughts on an old Vicarage

It has always seemed logical that Church House, situated almost in the churchyard, should have been the home of the village priest in the sixteenth century, before the vicarage in Vicarage Lane was built. This seemed confirmed by a list of landholders drawn up in 1587, which said that Thomas Oseland, who was vicar of the parish, rented a house adjoining the churchyard. This can only have been Church House: and the vicar was living in it, so it must have been the vicarage.

should have been the home of the village priest in the sixteenth century, before the vicarage in Vicarage Lane was built. This seemed confirmed by a list of landholders drawn up in 1587, which said that Thomas Oseland, who was vicar of the parish, rented a house adjoining the churchyard. This can only have been Church House: and the vicar was living in it, so it must have been the vicarage.

I wasn’t alone in this assumption, but embarrassingly I did state it in print a few times. But now, having thought more carefully about the old evidence, and looked at some newly-discovered documents, I am sure that Church House never was the vicarage at all.

Thomas Oseland, vicar from the 1550s to 1588, was actually born in Highley, the son of John Oseland who rented the manor house and lands from the Lord of the Manor, Sir John Littleton. And the house by the churchyard that he lived in was also rented from Littleton—as it would not have been had it belonged to the Church. Thomas was an old man: his parents had been dead for over twenty years. Church House was very convenient, and his family still had a lease on it, so Thomas simply stayed there.

A new family, the Peirsons, had come to Highley after Thomas’s father died and been given the lease of most of the manor farm (his mother Margery complained that the Peirsons had been harassing her to move). It seems most likely that they built the Manor House on the main road at this time – we know they lived there later, and in the seventeenth century it was remembered that Church House and the Manor House had ‘anciently been one farm’. Church House, then, must have been the original manor house.

Thomas Oseland found Church House convenient because his ‘real’ vicarage was quite a long way away from the church. We have a few pointers as to where it was. In 1557 there was a lane on the west of the main road running up through the village, parallel to it. This was called ‘Vicarage Way’: but it went nowhere near Church House. A list of the lands that did belong to the Church in about 1590 exists. Although it is rather ambiguous, it suggests that the house belonging to the Church – i.e. the vicarage – was situated near the glebe pasture lands which lay along the river in the north of the parish. In 1618 two lanes, called Woodend Lane and Haselwells Lane, ran north from ‘the vicaredge barn’. One of them was probably a continuation of Vicarage Way. It sounds as if by the early seventeenth century there was at least a barn pretty much on the site of the old vicarage in Vicarage Lane.

The house we know as ‘the old vicarage’ appears to date from about 1620 or so – when indeed it is clear this was the site of the vicarage. But I am now convinced that we were wrong in thinking that it was newly built here, and I believe that the vicarage had always been on or very close to this site. That would explain why parts of the house seem very ancient; and why we can find references suggesting the vicarage was in this area at an earlier date.

In 1532, Highley vicarage (wherever it was) had been reported to be in a poor state of repair. I suggest that this medieval house remained somewhat dilapidated – and so the vicar stayed in his family house, the old manor. Then when the open fields were enclosed in the early 17th century, the new vicar’s glebe lands were concentrated around the vicarage, which was comprehensively ‘done up’.

One mystery solved, though, leads to another. Why on earth was the medieval vicarage situated so far away from the church?

Gwyneth Nair

Stanley Cottage

Stanley Cottage sits by the River Severn. In modern times it has undergone a series of extensions which have significantly increased its size but much of its original character has been retained. Back in 1980, in her book, “The Old Houses of Highley”, Gwyneth Nair described Stanley Cottage as “one of the most enigmatic houses in Highley”; some 30 years later, its history remains largely mysterious.

The house first appears in the historical record in the late 18th century Berrow’s Worcester Journal of September 16th 1779 which had a sale notice for the Heath Farm. This was demolished when the railway was built around 1860 but stood between Stanley Cottage and Coomby’s Farm. The sale included “two tenements or dwelling houses in the holding of Thomas Parker and Widow Lowbridge”. We know that in the 19th century Stanley Cottage belonged to the Heath and so it can be assumed that the “two tenements” in this advert are in fact Stanley, which at that date must have been divided into two. Thomas “Parker” is almost certainly Thomas Barker, who married a daughter of Samuel Wilcox, owner of the Ship and the quarries behind Stanley Cottage. Widow Lowbridge had lost her husband in 1777; she seems to have fallen on hard times, as when she died she was described as a pauper. Paupers were the responsibility of the parish, who had to house them; it looks as though one of the two dwellings at Highley was leased out for this purpose.

Stanley next appears in the documentary record in 1823, when it had been acquired by a partnership that had operated a colliery by the river. The mine closed in 1823 and the cottage was included in the dispersal sale. It apparently had gone up in the world since 1779, for now it was described as a “commodious residence… which has at different times been occupied by a partner and a manager of the mines”. By the 1840s it had sunk back to its previous level as it was again divided into two halves, occupied by John and William Kirkham, quarrymen. Subsequently the two parts were reunited and was home to various members of the Lucas family for around a century.

The mystery of Stanley Cottage concerns its origins. Externally, it is a long, low building, made of the local sandstone; this would be consistent with construction in the late 18th century. However, there are a number of curious features. Photographs taken around the First World War show that it was roofed in sheet iron. This was typically used to replace thatch. However, tiles seem to have been common by the middle of the 18th century in Highley; it would be unusual for thatch to be used at such a late date. Inside, the first room at the north end of the house was a kitchen/living room, dominated by a huge fireplace. Whilst large fireplaces would be needed for cooking ranges, this seems big even by those standards, certainly for a semi-detached cottage. The structure has much more of the feel of a 17th century fireplace, serving a farm house. There currently is one door at the front, which faces the stairs with a wooden frame to its north which probably once was a part of a partition wall. The central door leading to a short passage again is a feature that might be expected in a 17th century farm house, not a pair of 18th century cottages. At the south end, the original fireplace seems to have been much smaller than its twin at the north end. When the house was divided into two, this must have been the kitchen of the second house, but it is difficult to believe that this was its original purpose.

Overall, many of the features of Stanley Cottage appear to be more consistent with a farm house built in or before the 17th century, not a pair of cottages built in the 18th century. On this basis, it may have its origins in one of the medieval farms of Highley. Such houses were almost certainly originally timber-framed, but were rebuilt on many occasions. Possibly Stanley started life as a farm house with a barn attached. At some point it may have been rebuilt in stone, with the barn turned into an extension of the main house. For unknown reasons, the farm was taken over by the owners of the Heath Farm, who then started the process of conversions that we can trace in the historical record. If anyone can shed further light on this house, I would love to hear from them!

Schoolhouse Cottage, Highley

Schoolhouse Cottage appears today as an unremarkable brick cottage; one of the last houses on the way south out of Highley on the New Road. The older generation of Highley residents may remember it as Miss Doughty’s cottage, when it was smaller than it is today, but still of the same general appearance. The Doughty family had lived in the cottage since the early 20th century and so it is not surprising that it should be known after the last family member to live there. However, the history of the cottage extends way beyond the period when the Doughty’s lived there.

The first reference to “Schoolhouse Cottage” is in 1759. In the vicar’s accounts, one George Loughton was charged for Netherton Farm and “Schoolhouse”. There is no doubt that this is Schoolhouse Cottage as a map exists of the lands belonging to Netherton Farm in the late 18th Century and which clearly shows the cottage. Loughton leased both Netherton Farm and Schoolhouse from a George Windle of Bridgnorth. Loughton was a farmer who lived at Netherton; he sublet Schoolhouse to a tenant. Whilst this is the first mention of Schoolhouse by name, it is possible to trace the history of the house back beyond this point as the previous year, Loughton features in another set of accounts paying for “Rowley’s” and “Crowder’s”. Netherton Farm had been held by members of the Rowley family for much of the 17th century, and so there can be no doubt that the two were alternative names for each other. Consequently, “Crowder’s” must be an earlier name for Schoolhouse. The trail can be pushed back further still. George Windle acquired much of his land in Highley from an estate once owned by the Corporation of Bridgnorth; the latter invested in land and used the resulting rents to pay for the work they needed to do in Bridgnorth. A deed of 1753 describes some of this “Bridgnorth land” that Windle had purchased. It was made up of two fields, Quaking Mire and Hollybush and a “messuage”; in other words, a house. Although the location of Hollybush has been lost, Quaking Mire was close to Schoolhouse and there is little doubt that the messuage on the Bridgnorth land was Schoolhouse. Corporation deeds show that the house was in existence in 1718. The Corporation purchased this estate in Highley in 1710; the sale document refers to the two fields and “half a messuage”, lately occupied by Dorothy Strefford. The interpretation of this is not so clear, but the simplest explanation is that the sale included a half-share in what is now Schoolhouse. If this is the case, then we can go back to 1687, when the messuage (i.e. house) of Dorothy Strefford on this land is first mentioned. So there is a very good chance that Schoolhouse was first built in the 17th century.

Further detective work provides a possible explanation of why the house was built. A deed of 1654 describes how Thomas Lowe of Borle Mill, the lord of the manor of Highley, built up a large estate in the village in the first part of the 17th century. In 1600, Quaking Mire and Hollybush were all part of South Field, one of the large open fields of Highley where each villager had a number of isolated strips of arable land. Thomas and the other large farmers swapped and bought up the strips to create distinct fields, to bring all their land together. Thomas seems to have taken the lead in creating the fields at Quaking Mire and Hollybush. He effectively established a small farm based around these. Having done this, it seems that at some point he leased them to another villager to work. However, once this had been done, the new occupier would want to build a barn and a shed for any livestock on the field; it was then just a small step to build a house to complete the farm. We know that a number of small farms were created by this process in Highley; it looks like Schoolhouse was one of these. Until well into the 20th century, there was a large timber-framed barn and a set of low, stone sheds next to the house built around two sides of what would have been a foldyard to hold stock, and we know that the early tenants under Bridgnorth Corporation and George Loughton were farmers. It is not clear when the house was used as a school. There was a school in Highley in the early 17th century, although this may be too early to have been at Schoolhouse. The alternative was that it was used as a school in the first part of the 18th century, perhaps by a tenant who combined farming with teaching. By the early 19th century it seems to have been let to a series of farm labourers, although by a strange quirk, in 1901 John Davies, the village school master, was in residence.

The house as it survives today looks largely to be 18th century, but it is possible that there are still some earlier features remaining.

The old houses of Highley: Cherry Orchard Cottages

Some 30 years ago, Gwyneth Nair produced a book on the old houses of Highley, describing every pre-1850 house in the village. This sold out very shortly after it was produced and has never been reprinted. However, Gwyneth has continued to research this subject and over the next few months, she and I will produce a series of updates based on her research. We start this month (February 2014) with Cherry Orchard cottages.

Cherry Orchard cottages stood close to Wren’s Nest, on the lane that runs from Netherton, eventually joining the New Road by School House. I write this in the past tense as they were demolished in the early 1960s. However, many of the older inhabitants of Highley will be able to remember them and they had an interesting history as shown by their alternate name of “Workhouse Cottages”.

From the time of Queen Elizabeth 1st, every parish was meant to make provision to look after their own “deserving” poor; those who could not support themselves either because of old age, illness or misfortune. Where possible, this took the form of cash payments or “outdoor relief”, paid to people living in their own homes. The alternative was to house people in the “workhouse”; as its name suggests, where at all possible, the inmates were expected to do some form of work in these institutions. A workhouse was expensive to build and maintain; whatever the inmates did rarely made more than a token contribution to the true costs of such establishments. Accordingly, parishes usually grouped together to build one central workhouse to serve the whole district. In the case of Highley, it was in a union of parishes based around Cleobury Mortimer.

However outdoor relief also had to be paid for and to deal with this a pair of villagers were elected each year to act as “overseers” of the poor. They had the power to fix a rate on the wealthier inhabitants of the village, to fund the payments they subsequently had to make to those in need. The poor rate was never popular and the overseers were under pressure to keep it as low as possible.

One way of keeping the poor rate low was to invest money in property and then use the rents to pay for the poor. The parish of St Leonard’s in Bridgnorth purchased significant amounts of land in Highley, both around Dowsley Cottage and also where the Pen Factory now stands from the late 17th century and leased these to local farmers. These feature in local records as “The Bridgnorth Lands” until the end of the 19th century. Perhaps this gave the overseers in Highley the idea of something similar, for around 1740, they approached one Robert Evans to build a row of cottages, to be owned by the parish. Evans lived in Highley and was a brick maker; no doubt he also worked as a builder. Evans agreed and built the pair of cottages that stood at Cherry Orchard. He was to be reimbursed from the poor rate, but there seems to have been a problem with this, as he was left £13-6-8 short and eventually agreed to accept the balance in sums of £1-10-0 a year.

My guess is that the original plan was simply to rent out the cottages; probably the income for the first few years went to pay off Evans. However, in 1758 it was recorded that the rents were used to pay for bread to be distributed weekly to the poor. Somehow the cottages acquired the name of “Workhouse Cottages” by 1851 and occasionally the overseers did pay the rents of one or more inhabitants of the houses. However, there is no evidence that the cottages were ever run as a genuine workhouse; there were a number of houses in the late 18th and early 19th centuries which were leased by the overseers for housing widows and invalids, presumably because they could not be placed in the central workhouse at Cleobury. The number of dwellings seems have to fluctuated between two and three; it would not have been difficult to squeeze in an extra family when the opportunity arose.

The use of the rents to pay for bread continued, whoever was paying for the cottages and this was formalised in the Cherry Orchard Trust. With the growth of the Welfare State in the 20th century, the need for bread distribution disappeared and was replaced by grants to widows. In 1960, the trustees approached Bridgnorth District Council for a grant for repair of the cottages. However, the council condemned one of the cottages as unsanitary and advised that the other was beyond economic repair. Initially the trustees proposed to demolish the cottages and replace them with a pair of old peoples’ homes, but they were refused planning permission. Eventually they were demolished, the land was sold and the proceeds were then invested at a bank. However, whilst the cottages have gone, the successor of the Cherry Orchard Trust still remains.

The old houses of Highley: Wren’s Nest

Wren’s Nest is the oddly named cottage found on the lane that goes from Netherton to School House Cottage. The name is not recorded until the 1861 census; it may have been a nickname to reflect a small and rather hidden house, well off the main roads. However, the house can be easily traced back to the first census of 1841 as it was always occupied by members of the Pitt family: James, a woodman, Mary his wife and George their son. Furthermore, it always occurs in the census returns next to Cherry Orchard, further confirming its identity.

The house currently gives few clues as to its age. At its heart is a two-storey stone-built cottage which had four rooms. In 1947 there was also a brick brewhouse with a bread oven. Documents allow us to trace the house back much further than the 1841 census. One of our best sources for the pre-census period are the yearly accounts kept by the vicar to record payment of tithes, and also the ‘Easter Offering’: effectively a rate levied on everyone in the village that went straight to the vicar. Needless to say, the payment of this was recorded with particular care!

There are also records of the rate levied each year to pay for the expenses of dealing with the poor of the parish. Collectively, these show that in the early 19th century, James Pitt and before him his father, Francis, owned what must have been Wren’s Nest. The house was a small farm; the Pitts owned some land (which still belonged to the cottage in the 20th century) and rented more nearby. Francis Pitt the father was probably born in Alveley in 1762 and married one Anne Dallow in Glazeley in 1788. Shortly after this, he moved to Highley to set himself up as a farmer with Anne and his newly born son James. At this point, he was rather more than a simple smallholder, for he took over the lease of the large Green Hall farm, now demolished but which stood in the fields beyond the Malt. He took over Wren’s Nest in 1795, but remained at Green Hall until 1806. In this year, he ‘downsized’ and moved with family to Wren’s Nest. We do not know why they moved, but it seems a downwards step and the probability is that it was forced on them by some kind of problem.

In these records, Wren’s Nest is called ‘late Minchall’s’. This reflects the fact that it was originally owned by one Mr Minchall. As Minchall’s we can trace it back beyond the time of the Pitt family to 1779, when the name first appears as an estate rented by Thomas Fenn. As Thomas is noted as paying for the ‘lower house as well as his own’, it seems very likely that the cottage was in existence at this time. Beyond this, the trail goes cold. However, earlier sources indicate the existence of a ‘missing’ house in the vicinity of Wren’s Nest. This is the house of the Lowe family.

At the start of the 18th century, Thomas Lowe was a tailor and small-time farmer, leasing lands in the vicinity of Wren’s Nest/Cherry Orchard and the site of what is now the Pen Factory. He lived in Highley and it is unlikely that his house would have been far from the land he rented. He subsequently bought the land and his son, Francis, sold two acres of it for the overseers of Highley on which they built Cherry Orchard, further confirming the location of the family estate. By the late 18th century, the family died out and perhaps at this stage the estate was sold to Mr Minchall. There is one further piece of evidence. Thomas Lowe, in his will of 1727, gives a partial description of his house, including the information that it faced south. Most houses in Highley are orientated east-west; however, Wren’s Nest is built on a north-south axis.

If Wren’s Nest is the missing Lowe family house, then it may date from some time in the 17th century. The Lowes were at one point Lords of the Manor; Thomas was descended from a younger son, but his branch of the family probably acquired their lands around 1650. We know that Thomas’s grandfather lived in a modest house with just two fireplaces in 1672 (at this date, fireplaces were taxed) and it is possible that this may have been Wren’s Nest, or at least a house in the same place. There is one final consideration. In the late 17th century, Wren’s Nest would not have been hidden away, off the beaten track; at that period, it would have been on the main road leading out of Highley to Bewdley.

Gwyneth Nair and David Poyner

The old houses of Highley: Rose Cottage (1)

In the later nineteenth century and for much of the twentieth, Rose Cottage, at the top of Smoke Alley, played an important part in the life of the village. It was the home of John Harley and then the Derricutt family. Harley was a wheelwright. So too was Mr Derricutt, but he also repaired farm vehicles (and, later, motor bikes), acted as undertaker, and toured the surrounding farms pressing apples for cider.

In 1945, when it formed part of the Netherton estate, Rose Cottage consisted of a hall, sitting room, kitchen, pantry, back kitchen, landing, 3 bedrooms, cellar, coalhouse and privy. There were also blacksmith’s and wheelwright’s shops in what were already old brick and stone outbuildings to a rougher stone rear. It was a fair size for a cottage, and had also over two acres of land, including a ‘good garden and well-fruited pasture orchard.’ In 1945 it was worth £700…

John Derricutt and his family moved here from Borle Mill when John Harley died in 1901. Derricutt’s wife, Emma, was a member of the Jordin family, owners of the Netherton estate. Harley had lived at Rose Cottage since at least 1871. He came to Highley from Worfield as a newly-married man around 1870, and first appears, as a wheelwright, in a trade directory and the census in 1871.

Before that it seems that there was no wheelwright as such in the village, though there were two blacksmiths and no doubt there was an overlap of roles. We lose sight of just who was living in Rose Cottage for a while in the middle of the nineteenth century, but luckily we can pick up the thread again and look further back in time.

Emma Mantle, a middle-aged single woman, lived here in the 1840s. She had been brought up in Rose Cottage: her father Francis was a quarry worker who was killed in an accident at a quarry in 1835. The Mantles had lived here since 1805. When Francis paid local tithes, his property was referred to as ‘Hughes’s’, indicating that Hughes was the owner and Mantle the tenant. Tellingly, Rose Cottage is also at this time referred to as ‘Hughes late Cooks’.

In fact these pieces of puzzle all come together when we look at the will of Sarah Cook, spinster, who died in 1805. Her main beneficiary was her nephew Edward Hughes. In the late eighteenth century, the Cooks were second only to the Jordins of Netherton in wealth and position in the village. They lived at the Manor Farm. So why was Sarah living in Rose Cottage? The answer is that the Cooks had bought the cottage in 1779 as a kind of dower house; what today we would call a “Granny flat”. Sarah’s mother, Elizabeth, had been widowed, and moved out of the farm to allow the next generation to take it on.

It seems that here too may be the explanation of the two contrasting halves of the cottage. The brick front looks to date from the later 18th century, and it is very likely that it represents the extending and modernising of an older cottage just up the road from the family farm. This would have made a cosy, chic home for Widow Cook (who died in 1788) and her daughter. They could have independence but still be close to family members. If this theory is correct, the additions to the cottage can be dated quite precisely to 1779 – 80, immediately after Elizabeth Cook bought it.

But what had the property been like before its makeover and transformation to a dower house? Read the second part of this next month to find out!

Gwyneth Nair

The old houses of Highley: Rose Cottage (2)

Last month I told the story of how Rose Cottage, the home of the village wheelwright around 1900, could be traced back over a century earlier, when an old cottage was purchased by the Cooks, one of the leading families in Highley, as a home for the widowed Elizabeth Cook, the matriarch of the family. We know that Cook moved to Rose Cottage from Manor Farm after the death of her husband Joseph. She bought the cottage and its two and three-quarter acres of land from William Rowley in 1779 for £190 – and apparently proceeded to renovate it extensively.

But what of the old cottage that stood on the site? It was almost certainly much smaller, and consisted of the back half of Widow Cook’s house. The first time that she paid tithe on her new possession was in 1780 – when her property was called ‘Charnocks’. Tracing back through the 18th century, we find the cottage sometimes referred to as ‘Rowleys’, after its owner, and sometimes as ‘Charnocks’. A couple of acres or so of land belonged to it, but this didn’t provide a living and so the occupiers must have had some other source of income. Probably they were artisans.

So we can identify families who lived in the cottage as tenants. Benjamin Pountney and his wife Anne lived here in the 1760s and 1770s. William Bayley was the tenant from about 1745 until his death in 1762. At this time, the cottage was still known as ‘Charnocks’, though at this stage there is no indication of why. It was also still sometimes called ‘Rowleys’.

This is explained when we get back to 1725, when William Rowley and his wife Constance bought the ‘tenement in Higley with appurtenances called Charnocks Tenement, with the garden and close thereto adjoining containing 2¾ acres’ for £115. The previous owner was Richard Cresswell of Netherton, lord of the manor. We even know some of the early tenants of the cottage – Thomas Low junior and Roger Gough both rented it in the 1720s. But having taken the history of Rose Cottage back to the early 18th century, we still haven’t established how it came to be called ‘Charnocks’.

For that we have to continue the trail back into the 17th century. In the tithe book of 1683 we find: ‘Mr Cresswell [paid]… for tithe hay of William Charnock’s tenement 1s 4d.’ At last we can see that the name attached to Widow Cook’s house in 1780 was already a hundred years old. It had been the home of the Charnock family, although it was owned by the Cresswells. Can we say for certain that the Charnocks’ house was the same as Rose Cottage? The chain of evidence is very strong. How much of the fabric of that cottage remains in the present building is hard to judge, but it seems likely that some at least survives.

The Charnocks, like later tenants, were artisans. In the early 17th century they were weavers, and also brewed and sold ale. In fact members of the family quite frequently came before the church courts at this time. In 1615 there was a rumour in the village that Alice Charnock had given birth to an ‘illegitimate’ child which, not surviving, had been buried in a garden. In 1622 William Charnock was reported for making up ‘foolish scandalous rhymes’, presumably about his neighbours. It seems that the family weren’t popular, and a clue may be found in the same church court of 1622: Ann Charnock was reported for not attending church. In fact the Charnocks were the only family in the village still adhering to the old Catholic religion.

The Charnocks, like later tenants, were artisans. In the early 17th century they were weavers, and also brewed and sold ale. In fact members of the family quite frequently came before the church courts at this time. In 1615 there was a rumour in the village that Alice Charnock had given birth to an ‘illegitimate’ child which, not surviving, had been buried in a garden. In 1622 William Charnock was reported for making up ‘foolish scandalous rhymes’, presumably about his neighbours. It seems that the family weren’t popular, and a clue may be found in the same church court of 1622: Ann Charnock was reported for not attending church. In fact the Charnocks were the only family in the village still adhering to the old Catholic religion.

How much of this can we say happened at Rose Cottage? We can identify Charnocks there in the later 17th century with reasonable confidence. Earlier, we know that they lived in a cottage with a small amount of land somewhere in the village centre, and it seems more than likely that this was their home. It’s unusual to be able to do this with a house smaller than a farm, which makes Rose Cottage a special case.

Gwyneth Nair

The old houses of Highley: Oak Cottage

In 1705 Thomas Pountney, living in Bewdley, left his houses in Highley to his son, John. This branch of the family was quite well-off, and at least one of the houses was a substantial one. John in turn, in his will of 1729, bequeathed to his ‘kinsman John Pountney the house he lives in.’ This ‘kinsman’ was probably a cousin, from a less wealthy branch, and the house a small one. The grandson of this cousin John, born in 1751, we know lived at (and owned) Oak Cottage. We can trace his life here in some detail. So it seems reasonable to suppose that the house his grandfather inherited was also Oak Cottage.

At least six successive generations of John Pountneys lived here – very confusing! John, born 1751, and his wife Ann, brought up their children here, but she died in 1800. By 1790, John was living here with his son, also John of course, together with Samuel and Elizabeth Bright (née Pountney).They kept chickens together, but the cottage didn’t have enough land to support them.

Some of the overcrowding was eased in 1806 when John the younger married and moved out to Chelmarsh. But it must still have been a squash in the tiny cottage. Then in 1814 something happened to disturb the house-sharing which had gone on for nearly 25 years. A scandal! The Brights moved out, and the parish Easter Book records ‘John Pountney and woman’ here, instead of the usual formula of ‘and wife’. She was Elizabeth Giles, a widow. The vicar didn’t really know how to describe her: the following year he thought perhaps she was the housekeeper, and recorded her as ‘maid’. Thereafter he settled for simply E. Giles, widow.

Elizabeth stayed on after John died in 1820 at the age of 68. Her son, Edward, bought Oak Cottage in 1827 from John the younger in Chelmarsh. Elizabeth was getting on by now, and a grandson came to live with her for a while. Eventually she died in 1832, aged 76. Edward Giles sold the cottage to William Jordin in 1840, when its situation was clearly described – it was bounded on the west by a public highway (the main road) and north by a lane used as an occupation road (Smoke Alley). William Kirk lived there. He was a shopkeeper, though we don’t know what he sold, or whether Oak Cottage was also his shop.

All this time, there is no mention of the name Oak Cottage. In fact the first clear use of the name was in 1911, when Elijah Mayer, who had come from Silverdale in Staffs to work at Highley Colliery, lived here with his small family. There were four rooms, according to the census.

When the Netherton Estate was sold in 1945, Oak Cottage was listed as ‘Half-timbered brick & tile ... containing living room, sitting room, pantry, two bedrooms.’ There was also a ‘lean-to outhouse with sink & boiler, privy and coalhouse.’ The cottage had electricity, but surprisingly neither running water nor a well. Water, we are told, was ‘from a tap in the village’. Earlier, occupants must have got their water from the town well, not very far away. It might be expected that the tile roof replaced an earlier one of thatch, but some of the current tiles are of a considerable age and hand-made. One has the paw print of a dog or fox, that clearly wandered over it whilst it was still drying before being fired in a kiln.

When the Netherton Estate was sold in 1945, Oak Cottage was listed as ‘Half-timbered brick & tile ... containing living room, sitting room, pantry, two bedrooms.’ There was also a ‘lean-to outhouse with sink & boiler, privy and coalhouse.’ The cottage had electricity, but surprisingly neither running water nor a well. Water, we are told, was ‘from a tap in the village’. Earlier, occupants must have got their water from the town well, not very far away. It might be expected that the tile roof replaced an earlier one of thatch, but some of the current tiles are of a considerable age and hand-made. One has the paw print of a dog or fox, that clearly wandered over it whilst it was still drying before being fired in a kiln.

So how old is Oak Cottage? The main part is timbered and may date from the late 17th or early 18th century. But there was probably an earlier house on or very near this site, which seems to have been in the Pountney family for what could be a very long time before that. It is quite rare to be able to trace so much of the history of a relatively modest home as opposed to the major farmhouses of the village.

Gwyneth Nair

The old houses of Highley: Coombys

’Coombys’ might seem an odd name for a farm, but fortunately we can explain it. The farm has never been large: when it was sold as part of Netherton estate in 1945, there were eight acres of land attached. Indeed well into the early twentieth century, Coombys was no more than a small-holding. In 1901 and in 1911 James Jones, a coal miner, was living here with his family. It seems as though his wife kept a few cows, although at both times there was a resident farm labourer who may also have helped. There was also an orchard; the farm has always been associated with cider making. There were also five lodgers in 1911. Subsequently Bob Corfield, then Tom Cadwallader, took over and by 1941 the latter was farming 44 acres, concentrating mainly on milk but also with a few sheep, pigs and fowl.

The house was quite large – there were eight main rooms in all in 1911 and in 1945 the house had a sitting room, kitchen and back kitchen, wash-house, dairy, cellar, three bedrooms and three attics. The size seems to have resulted from various additions made since it was built, with a middle section representing the original house, probably of early 18th century origins. All sections were stone-built, appropriately for a house long associated with quarrying.

Coombys was farmed by William George in the late 19th century. Before that it stood empty for a while, after the death in 1863 of Sarah Wilcox, the 81 year old widow of William Wilcox, who had been running the farm. Sarah appears in several trade directories in the previous decade as a farmer of ‘Coombys’ or ‘Coombies House’, which in 1861 had nine and a half acres of land.

William and Sarah had lived here for many years. He was described in 1851 as a barge owner and farmer (the Wilcox clan ran The Ship and barges on the Severn) and in 1837 as a ‘stone merchant and barge owner’. We learn from a voters’ list of 1836 that William owned the freehold house and land at ‘Combeys’. The ten acres were also being farmed at this time. William has left a carved stone at the farm “WW1823”, presumably to mark some building that he did.

William took over from his father Samuel Wilcox. Samuel owned other land, and at first had only rented Coombys. In the 1790s he regularly paid tithe on ‘his own and Coombys’, and at this time the latter was owned, oddly enough, by Obadiah Whitcombe of Green Hall – almost as far away in the parish as you could get. Samuel was very active in the quarrying developments near Coombys in the 1790s, and it was probably at this time that additions were made to the original house.

The first record of Samuel at Coombys is in 1779, when ‘Owner Wilcox’ paid tithe ‘for Combys’. This is a title given to barge owners, and doesn’t mean he owned the farm. Indeed that was owned by the Fox family, predecessor of Whitcombe at Green Hall. Although Coombys was linked to river trade and to quarrying, it was still a farm – in 1786 it was referred to as ‘Combys late farm’.

And here we get to the explanation for the name. For until 1774 the farm had been occupied by Thomas Coomby or Comby. He is first recorded in Highley thirty years earlier, in 1744, having come from Chelmarsh. These mentions are in parish accounts, where Coomby pays for ‘the parson’s land’ or ‘Mr Higgs’ estate’. The vicar, Richard Higgs, was until his death in 1756, involved in extensive quarrying at what he called ‘my land in Highley at Severn side.’ Hearth stones went from here to the furnaces at Willey and Leighton.

It was on this land that Thomas Coomby came to live, and probably built the house. Its central portion is in a style suggestive of an origin in the earlier 18th century. There is no sign of anyone living here earlier, though of course it is possible. It isn’t clear when Rev Higgs acquired the land either, but he was recorded quarrying on his land from the 1720s. Neither is there any evidence that Coomby was quarrying – he simply rented land and farmed here, in a small way.

So the oddly-named Coombys was linked to farming, quarrying and river trade, the three chief occupations in the village before coal mining.

Gwyneth Nair

The old houses of Highley: Paddock House

Now we come to look at a house that you’ve probably never heard of. It’s one of the ‘lost houses’ of Highley. We must begin with a piece of land: Earnwood Park was a medieval deer hunting park and extended over the Borle Brook into the parish of Highley in its south-eastern corner. At that time, the word for a park was ‘parroc’, which easily got corrupted into Paddock. So land in this small area came to be known as Paddock.

This makes it difficult to see just when a house was built on this land. References to Paddock or the Paddock might not mean there was a house here at all. But then in the 1720s we can be sure that a house did stand here. In 1721 Thomas James of The Paddock was buried. This means he lived here – and he probably had done so for some time, for Thomas James and his wife Katherine were in Highley from at least 1680, at which time his father also lived with them. Of course, they might have lived elsewhere in the village, but it seems likely that there was a house here long before the 1720s.

After Thomas died, Benjamin Elcock lived here briefly – he is recorded in 1724 – but the land seems to have been owned by John Bell. From this time, Paddock is often linked with The Heath, a nearby farm that we shall investigate soon. Thomas Rowley senior lived here next, buried in 1738 ‘of The Paddock’.

In the 1740s we find an alternative name for the Paddock – it appears sometimes as Pothook, a name which continued into the 19th century as a field name. But Paddock continued to be used, and there are many references to payments of tithes of ‘Heath and Paddock’, which doesn’t tell us who was actually living in the house.

It may well be that Rowleys continued to live here, as Widow Rowley was certainly living in this part of the parish towards the end of the 18th century. She lived alone, and kept bees, which is all we know about any farming activities here at this time.

Then into the 19th century the picture becomes clearer, as place of residence begins to be recorded in parish registers. We now know that there was definitely a house here. Thomas and Anne Barret came from Kinlet in 1799 and lived at ‘Pothook’, as it was now more regularly called, for 25 years. They were followed in the late 1820s by the family of John Ward, and then by Joseph and Martha Wilmot. Both men were farm labourers.

Paddock House could not have been particularly large, but it was bigger than a cottage. On a pew plan of the church dating from the late 1770s, Paddock House was assigned part of a pew for its inhabitants, as were all the chief houses of the village. The rest of the pew was for Dowsley, which may indicate houses of a similar status.

Just as the date of building Paddock House is unknown, so is the date of its abandoning. The last recorded inhabitants were the Wilmots in 1831. By the time of the tithe map and apportionment less than ten years later, there was no sign or mention of a house. However, the map does show a lane adjoining the field called Upper Paddock – and the original drawing for the first Ordnance Survey map of 1815 seems to show a house in very much this same area. By 1840, this had become part of the Heath farm.

So here in the far south of the parish was something of a mystery house – it stood for well over a century, probably a lot more, yet no trace of it remains on the ground. Or does it?

Gwyneth Nair

The old houses of Highley: Heath Farm

Like its near neighbour, Paddock House, the Heath Farm no longer stands. But unlike Paddock House, we have a good idea of just where it stood, and when and why it ceased to exist.

Both Paddock and Heath were names of pieces of land, and in neither case is it clear when a house was first built. In his will of 1654, George Peirson, who lived in the manor farm, left to his son Thomas one parcel of land … called The Heathe, late divided into several parcels, about 20 acres altogether. However, by 1663 the Heath, ‘some of the land of Peirson’s farm’ had been purchased by Rev Thomas Wright. There was still no mention of a house. Then in the record of a tithe dispute in 1677, we find that ‘Thomas Wright, clerk, is seised of a messuage and farm called The Heathe.... part of an ancient farm called Peirson’s Farm.’ This means that he owned The Heath and that it now had a house on the land, suggesting that the house was built between about 1663 and 1677, although there is no certainty that there was none here earlier.

Rev Wright didn’t live in the house, and in fact we have no idea for some time who did. Farmers from Hazelwells and Borle Mill rented the land over the following years.

From the 1720s, Heath and Paddock are often mentioned together. Thomas Rowley, who lived at Paddock House in the 1730s, was recorded as ‘of Heath’ in 1722. By 1728 ownership had passed to John Bell, who also owned The Paddock, but seems to have lived at The Heath, at least for a time. Then although he still owned the farm, others seem to have lived here: William Yates in 1740, and Richard Shineton during the 1750s.

In 1756 John Edwards lived at The Heath Farm, as it was now called, and kept a female servant and a live-in man farm worker. We don’t have any idea of the size or appearance of the house. But in 1776 Benjamin Crane, who that year married Mary Jordin of Netherton House, paid tithe of £2 18s 4d for ‘the Heath estate’, quite a substantial sum.

Nevertheless, Crane had only a 21-year lease on The Heath, and was the sitting tenant when it was advertised for sale in 1779. The farm was a respectable 86 acres in size. In fact the Cranes stayed here, raising a family, until 1803. Meanwhile, the new

coal mine at Stanley had been opened quite nearby, and in the early 19th century partners in the colliery took over the lease and some lived for a time in the house.

When Stanley was wound up in 1823, The Heath was described as ‘A commodious residence contiguous to, but out of sight of, and free from annoyance by, the

mines or works; seated on an eminence overlooking the noble river Severn, and commanding a fine prospect, with a farm of about 70 acres of land.’ Still no word, though, on what the house looked like.

With the closure of the colliery, The Heath reverted to agriculture. By 1840 it was owned by William Haslewood of Kidderminster and occupied by William Wilcox. Wilcox left in 1847, selling up his farm stock and equipment. It had been a mixed farm, with horses, cows and sheep as well as ploughs for arable farming. Perhaps he had seen the writing on the wall, for in 1846 plans had been drawn up for a new railway along the Severn which would pass very close to the farmhouse.

But Richard Tomlinson came from Stone and took over the farm: in 1861 he was still here, farming 100 acres. However, the railway was going ahead, and when a reporter from the Bridgnorth Journal came to look at its progress in 1858, he said that the Heath farmhouse was very close to the new railway, and due to be pulled down. By 1871 the Heath was empty, and by 1882 vanished altogether. Its large and impressive barn, a bit further from the railway, survived for some time. No-one seems to have

photographed the house or even described it. But it would be wonderful if something turned up!

Gwyneth Nair

The old houses of Highley: Little Netherton

We know a lot more about the origins and history of Little Netherton than many other village houses. Still, some mystery remains.

In 1796, the will of William Jordin of Netherton House left the house and much land to his eldest son, William. But he also left land to his second son Thomas. Thomas married soon after his father’s death, and had a new house built for himself – his descendants dated this as 1799, which fits very well.

The house was a good size and in a fashionable style, very suitable for the younger son of the ‘Squire’s’ family. Thomas and his wife, Ann, raised their family here, including two sons, Thomas (born 1800) and Levi (born 1811). Thomas farmed, and they had a live-in maid and sometimes a resident farm labourer too. Thomas died in 1837 at the age of 64. His eldest son Thomas inherited Little Netherton, but was farming elsewhere, so Levi took over at Little Netherton, heading a household that included his wife and young children and his widowed mother.

By 1851, Levi had moved out, their mother had died, and Thomas and his sister Mary Ann, both unmarried, had moved back in. We know from its position on maps that their house was indeed Little Netherton, but so far that name had not been recorded. In Bagshaw’s Directory of 1851 it is confusingly called Netherton House (the ‘real’ Netherton House was still called New House).

In 1860, when he reached the age of 60, Thomas retired from farming. The farm was leased to John Oakley, and he and his family moved into the house. Thomas stayed on as a lodger, living in ‘apartments’ in his own house. Ten years later, he had moved out and was lodging elsewhere in the village. Meanwhile his cousin, Daniel, had moved here from Borle Mill. All this time, the farm had been about 30 acres, not large enough to support a family, servants, and such a smart house, one would think. But the Jordins did have revenue from other properties that they owned in the village.

Thomas was still the owner, and when he died in 1880 he left Little Netherton (by now it was being given that name) to his niece, Eliza Jordin, and her husband, John Derricutt. But they did not immediately move into the house and its small farm. Instead, while farming in a bigger way at Billingsley and then Stottesdon, they leased Little Netherton out to a series of tenants. Edward Davies late in the 19th century was followed by Herbert Maund early in the 20th. He sold up in 1910 and James Brick moved in.

John Derricutt died in 1919 and his widow Eliza (née Jordin) came back to Highley and settled at Little Netherton. She was still technically farming here in 1929, and died in 1931 at the age of 89. Her daughter, Annie, born in Highley in 1882, lived on here alone, very knowledgeable about and proud of her Jordin ancestry.

But we mentioned an element of mystery. The foldyard and barn of Little Netherton farm were quite some distance from the house. Jordins already owned this land when William senior died in 1796 and Thomas built his house on it. Did the barn, which certainly looks older than the house, already exist at this time, and Thomas build his new house at a genteel but still practical distance from the farm buildings? If so, what farm did they belong to? There may be a clue. It seems that in the early 20th century the Derricutts referred to Little Netherton as ‘Netherton Dallows’. Does this preserve an oral tradition of an earlier name? For there was a farm in Netherton, occupied by Dallows right back into the 16th century. Richard Dallow in 1603 had a farm of ‘arable 15 acres; pasture 12 acres; meadow 3 acres.’ A thirty-acre farm. Coincidence?

David Poyner