17th Century Chelmarsh

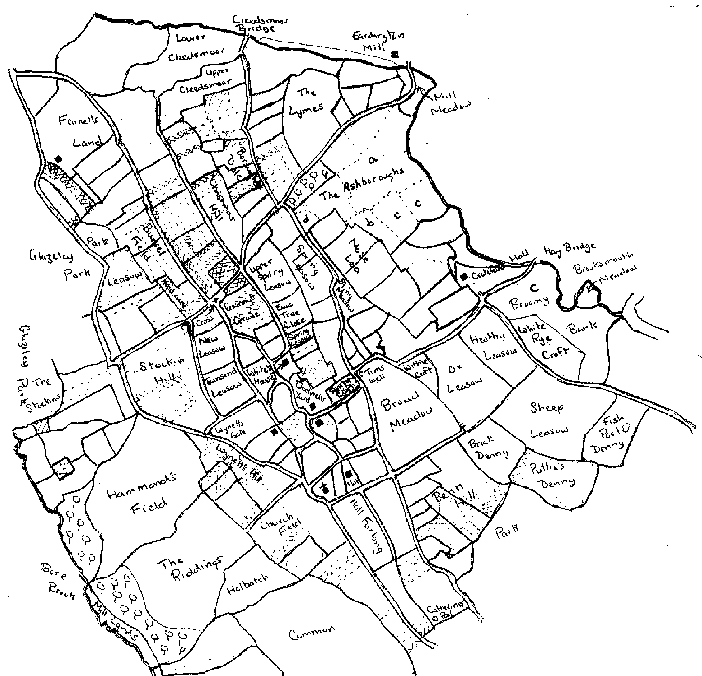

A few years ago, Gwyneth Nair drew my attention to a map of the north of Chelmarsh, originally drawn up in about 1630 by one Samuel Parson. The current main Highley-Bridgnorth Road can be traced from the bottom of the map, winding its way past the church and then turning sharp right, eventually going past Crateford Hall and over Hay Bridge. There were many other roads which are not just footpaths or which have vanished altogether. Also note the cross, marked near the centre of the map; this provides the main documentary evidence that the cross in Chelmarsh churchyard was once sited elsewhere. This has recently been supported by archaeological study of the cross during its restoration. The map is in the Shropshire Records and Research Office, Shrewsbury, reference 1671/1/Map1.

Deuxhill Chapel

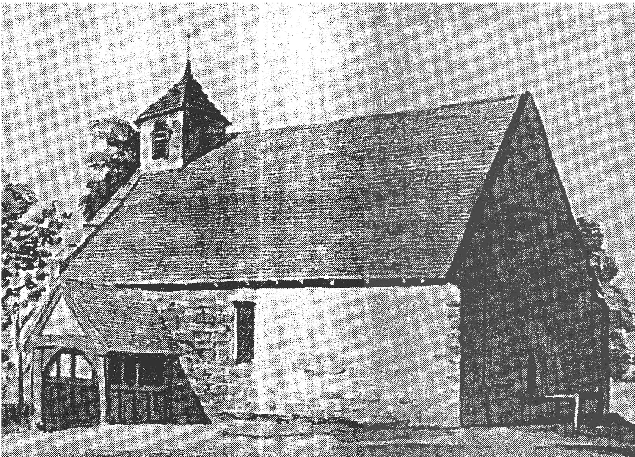

The tiny settlement of Deuxhill is easily overlooked. Today it is essentially a couple of farms and a few buildings alongside the Bridgnorth-Cleobury Mortimer road. It has long since been absorbed into surrounding parishes for administrative purposes. However, it was once a separate parish in its own right with its own place of worship. Long since disused, even today a few fragments still remain.

In the Anglo-Saxon times, Deuxhill was an estate that was given to Wenlock Abbey by its landowner, along with Chelmarsh and Eardington. The last two quickly passed to other owners, but Wenlock retained ownership of Deuxhill until the abbey itself was dissolved by Henry VIII. Wenlock Abbey probably built a chapel at Deuxhill in the early 12th century. The chapel consisted of a chancel and nave with a bell turret. The chapel was built at a time when the rural economy was booming; following a series of poor harvests and the Black Death in the 14th century, the local population fell and became impoverished. It is doubtful whether Deuxhill ever recovered and it is unlikely that it could justify its own place of worship. In spite of this, the chapel somehow managed to survive the next 5 centuries. The chancel seems to have been abandoned and demolished in late medieval times. A timber porch was built in 1661 by Anne Hassold, the lady of the manor. In 1759 the church was described as very ruinous but must have been subsequently repaired, for in 1793 it was considered to be in reasonable repair. Inside the church was a communion table, 9 pews and a pulpit. The bell tower had two bells in the 1730s but one of these was broken and was later scrapped. The church had a number of memorial tablets to local 18th century farmers such as the Corfields and also some lords of the manor such as John Lewis.

In the Middle Ages, the church was first united with Middleton Priors, a parish that also belonged to Wenlock. Later it was united with Glazeley. In medieval times it is possible that a few rectors lived in Deuxhill, but afterwards the majority probably lived at Glazeley or Chetton: larger and more prosperous communities.

In 1793 morning service was held at Deuxhill on alternate Sundays, with a communion service twice a year. In 1851 there were 30 adults at an afternoon service with 26 children at Sunday School. However, it is likely that these figures were made up of people from Deuxhill, Glazeley and Chetton. In 1875 the congregation transferred to a new church at Glazeley and the old chapel was demolished in 1886, apart from part of the north wall which still stands.

I can add a personal story connected with the history of Deuxhill chapel. According to family tradition, an ancestor of my mother’s grandfather was buried at Deuxhill. Some time later a farmer attempted to build a rick in the old churchyard. The story goes that the family claimed that the rick was over the grave and the farmer was forced to move it.

Although most of the chapel has now gone, it is still possible to see the remaining wall from the main Bridgnorth-Cleobury road, in the grounds of Church Farm, Deuxhill. Perhaps a suitable site for a Cluster service one summer afternoon?

The town of Stottesdon

Today Stottesdon is a modestly-sized village; the centre marked by a group of houses and farms clustering around the church. The parish is large and includes the distinct community of Chorley, as well as small collections of houses and farms at places such as Prescott and Overton. It is a vibrant place which recently recorded their history in a book “The Stud on the Hill” (from the meaning of Stottesdon). However, it has no pretensions to be anything other than a village. It was not always so.

At the time of the Domesday Book, Stottesdon was one of the largest places in South East Shropshire (neither Ludlow nor Bridgnorth are mentioned). Domesday records the population of places, gives an idea of the area used to grow crops and records the value of the settlement to the landowner. Highley may be taken as typical of most places; it had a population of about 60, about 300 acres were under the plough and it was worth 15 shillings a year. By contrast Stottesdon had about 500 people, farmed 900 acres and was worth £20 a year. Its boundaries included the southern slopes of the Clee Hill; a large chunk of the Wyre Forest in Kingswood and Dowles was a detached part of the manor. Of other local places, only Cleobury Mortimer was comparable.

Stottesdon belonged to Earl Edwin, who controlled most of the Midlands and whose ancestors had originally ruled this area as independent kings. Significantly, Stottesdon was one of the few places in Domesday where a church is mentioned; one of the signs of an important settlement. There are still a few fragments of Anglo-Saxon masonry to be found in the church today, including a carving over the main door. From late Saxon times each county was divided into areas called “hundreds”. Stottesdon was at the heart of its local hundred. Originally the administrative centre was at a place called Condertree, close to Walton Farm just to the south of Stottesdon but after the Norman Conquest this was moved to Stottesdon itself. Here justice would be dealt with in courts, taxes would be collected and all manner of administration dealt with.

Following the Norman Conquest, Stottesdon eventually came into the hands of King Henry I. He and his successors granted it to a series of royal favourites, at the same time breaking up the original structure. The Norman kings appear to have been particularly unfortunate in their choice of friends, as many of those who they rewarded subsequently rebelled, resulting in the confiscation of their estates which were then passed to others. This happened in Stottesdon, resulting in a whole series of owners. In the 13th century there was a particular fashion amongst the nobility for the establishment of towns. This meant that the inhabitants of a particular place would be granted a charter, giving them a measure of self-government and other privileges. In return, the lord would gain extra income from rents. At its best, a thriving market town would result, leading to prosperity for both the lord and the leading citizens of the town, the burghers. In 1244 the lord of Stoddeston, John de Plesstis, Earl of Warwick, was allowed to hold a market at Stottesdon every Tuesday and a fair on the 14th, 15th and 16th of August each year. Unfortunately the market could not have been a success. Bridgnorth and Cleobury Mortimer were growing in importance; Stottesdon was squeezed between the two and lost out. As late as the 17th century, there are references to “burghers” at Stottesdon. However, these must have been anachronisms; by then it was just another village.

Apart from the church, little obvious remains from these times. However, a recent study has suggested that echoes of Stottesdon’s past can still be seen in the shape and organisation of the old village. North-south and east-west roads appear to converge on the village centre; this is laid out roughly in a square, where the market was once held.

Kinlet – Flying Childe

As I write this, the ban on hunting with hounds has just come into law. This provides a convenient excuse to look at the career of one of the more interesting local characters from two hundred years ago, William Childe of Kinlet Hall, huntsman and agriculturalist.

William was born in 1755, the son of Samuel Baldwyn and Catherine of Aqualate Hall in Staffordshire. Catherine was the daughter and heir of William Lacon Childe of Kinlet. Childe had rebuilt Kinlet Hall and was a significant landowner with estates in Kinlet, Highley, Stottesdon, Neen Savage and Cleobury Mortimer. In his will, he left his estates to his grandson William on the condition that he change his surname from Baldwyn to Childe. It appears not to have been a very hard decision for young William to take and on his coming of age he inherited his grandfather’s estates.

William had two great passions in his life: hunting and farming. According to his contemporaries, he excelled at both. For reasons that are not clear to me, he appears to have spent considerable time in Leicestershire where he came into the circles of two men: Robert Bakewell and Hugo Meynell. Bakewell was a farmer who pioneered selective breeding in sheep to give the New Leicester breed. Meynell applied Bakewell’s methods to dogs to produce hounds who could sustain a lengthy and high speed chase of a fox across the newly enclosed Leicestershire grasslands. Prior to Meynell, hare coursing had been the most important form of hunting; foxes in many parts of the country had long been regarded as vermin and had been destroyed as part of routine pest control. With new specially bred hounds, fox hunting rapidly grew in popularity.

William, in visits to Leicester, must have made the acquaintance of both men. From Bakewell he developed an enthusiasm for the New Leicester sheep, a breed he pioneered in Shropshire. He also was a noted breeder of Devon Cattle, another of the new “improved” breeds of farm animals. He was also an admirer of the Suffolk Punch horse at a time when most Shropshire farmers used any horse that they could purchase. The annual Kinlet sales of livestock gained a county-wide reputation and proved a lucrative source of finance for the Kinlet estate.

When William was not buying animals from Bakewell, he seems to have been riding with Meynell’s Quorn Hunt. He developed a particular style, riding as close to the hounds as possible. This gave him his name of “Flying” Childe and this became the accepted way of following the hounds. Childe brought fox hounds back to Shropshire and kept his own pack at Kinlet. This must be the origin of the Dog Kennel house on the Kinlet estate. He regularly hunted over most of South Shropshire, in the areas currently covered by the Ludlow and Wheatland Hunts. In the late 18th century, fox hunting became very popular amongst the Shropshire gentry and squirearchy. As a landowner, Childe was barely in the second rank in the county; through hunting he could mingle with the county elite as an equal.

Childe has left a lasting impression on the local landscape. Apart from buildings at Kinlet, such as the Dog Kennels and the stables at the hall, the fields and woods bore witness to his enthusiasms. Even today, there are numerous small stands of trees on the former Kinlet estate which have no obvious economic function. These would have been encouraged by Childe as providing cover for foxes and other game. The pattern of fields on the estate in Kinlet and Stottesdon was largely laid down following his instructions, as he swept away the older irregular enclosures. It is interesting to see here how hunting and farming came into conflict. As a huntsman, Childe would have wanted large open spaces without hedges and fences to allow unobstructed gallops. As a farmer, he would have preferred numerous regular fields to control his livestock. Maps of the estate show that it was the farmer in him who eventually won. The area around Kinlet Hall was largely open in 1786; by 1810 it was divided into fields. Today Childe is better known as a reforming farmer than a pioneering huntsman.

Kinlet – Logwood Mill

Some time ago, I sketched out the history of Malpass or Logwood Mill. Recently more information has become available on this mill. Logwood Mill was located on the Kinlet side of the Borle Brook, just below Kinlet Colliery. However, it did not take its water supply from the Borle but from a minor stream that rises by Catsley in Kinlet and flows past the colliery into the Borle.

The mill was built on land that, in the middle ages, was part of the park of Earnwood. This was essentially a deer farm, to provide animals for the owners of the park, the Mortimer family. In the 16th century the park was leased by the crown to a variety of owners. In 1565 it was held by Sir George Blount of Kinlet Hall. A survey describes how the park was ruinous and ripe to be converted to farmland. However, it was not Blount who benefited from this, for Earnwood, with most of the rest of the Wyre Forest, passed to Sir Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Dudley did not acquire land for the view. He was a hard-headed business man, who required his estates to make money for him. In the Cleobury part of the forest, he set about doing this by building two blast furnaces. These used locally-mined ironstone and charcoal made in his own woods to produce iron. There is little doubt that he used the woods in Kinlet for a charcoal supply. However, in Earnwood Park he had a different plan. He seems to have felled what remained of the woods and converted the whole area to agriculture; most of the current Severn Lodge farm was probably carved out of the former park.

At the time Dudley was doing this, grain prices were increasing steadily. It was profitable to grow cereals. It seems likely that Dudley realised that, with the increased grain that was being produced on his newly established farms, there would need to be new mills to convert this to flour. Thus he may have taken the decision to build the corn mill that was to become Logwood mill. At any rate, it is certain when Dudley took over Earnwood in 1565 the mill had not been built; a year before he died, in 1587, it was at work. It is entirely in keeping with Dudley’s work in Cleobury that he should have also taken the lead in building the mill.

By the late 18th century the mill had found a new use as a logwood mill. Logwood was the name given to the heartwood of the tropical hardwood Haematoxydon campectonium, imported from Central America. This yields a dark blue or black dye, used in the textile and leather industries. The wood was cut into short lengths, reduced to chips and then ground to a powder. The powder was then used by dyers to produce their dye. It seems likely that logwood chips would be taken up the Severn as far as Bargate, taken the short distance to the mill by road and then ground to a powder. The journey would be reversed and the powder would be taken to Bewdley or beyond to be sold.

The grinding of logwood was the final work undertaken at the mill. However, it seems that the building survived for 50 or so years after milling ceased. It is likely that it was converted to a cottage. In the early 19th century around three families lived at Logwood (I have previously written about Ann Broom, “strumpet” of Logwood mill). The old mill was probably knocked down about 1850 but a cottage remained on the site until the 20th century.

Middleton Scriven mill

For the past two years, the Four Parishes Heritage Group have spent most of their time investigating two medieval ironworks in Chorley. This work will continue but in 2009 we will be taking on a new project in Middleton Scriven.

From the very start of agriculture, cereal crops such as wheat and barley have been staple foodstuffs, used to make bread and for brewing. However, prior to use the grains need to be broken open. This was initially done by hand; the grains would be rubbed between two stones to grind them down. This is hard and lengthy work; typically a woman would spend most of the day processing grain in this way, whilst her husband was at work in the fields.

In this country, it seems that it was the Romans who first mechanised the process by driving the stones by water in the first water corn mills. The impact on communities would have been enormous; within each family one person would have been relieved of the full-time job of hand-grinding and so would have been able to work at more profitable jobs such as spinning or weaving. The development of the water mill in many ways was the first step away from subsistence farming to a consumer society.

Whilst the Romans introduced water mills, it took around 1000 years for them to become common. At the time of the Domesday Book, roughly a quarter of the communities in Shropshire had water mills. Not surprisingly, they were found in the larger villages and in areas best suited to grain production. There were no mills in Highley, Kinlet or Billingsley, but they were found at Stottesdon and Glazeley. At Chetton, there was a new mill, showing how they were spreading. It seems likely that over the next 200 years, almost every village had a water mill. There was a mill in Highley by the late 13th century and mills are recorded in Billingsley and Kinlet in the 14th century. The number of mills remained largely static until the 18th century, but thereafter they declined. Initially the small mills were abandoned in the face of competition from those in the larger villages; Borle Mill in Highley prospered whilst Billingsley and Kinlet were abandoned. However, large mechanised mills in towns in the late 19th century eventually killed off all the rural mills; Borle Mill did little milling after the Great War.

We know surprisingly little about the small village mills. They were often abandoned before the coming of large scale maps and so they can be difficult to find. Their sites are vulnerable to damage by flood or agricultural improvements. The mills that survived until later were often completely rebuilt in the 19th century so their original form is lost.

In Middleton Scriven, there are the unmistakable earthworks of a small mill. They are complete; it is possible to identify the dam, the water course, the mill pool and the probable site of the mill itself. The mill is completely undocumented; however, there is a medieval mill stone close to its site, suggesting it started life in the 12th-14th centuries. It had certainly been abandoned by the start of the 19th century, probably as a result of competition from Horsford Mill on the main road in Deuxhill. Thus it seems to be a typical small rural mill, but there is a good chance that it will retain much of its original form.

We have been fortunate enough to obtain grants from Awards for All via the National Lottery, Grassroots from the Community Council of Shropshire and the Robert Kiln Trust which will allow us to investigate the mill archaeologically, by geophysics and excavation. We anticipate starting work in the Spring (2009).